By Travis Fisher and Nick Loris

Advocates of large-scale transmission expansion have recited a simple slogan for years: There is no transition without transmission. By this, they mean that the shift to renewable energy will require vast new power lines. Whatever one thinks of climate policy, that argument no longer carries much weight. The relevant question now is whether building more transmission will make electricity more affordable.

Yes, expanding transmission can reduce electricity costs for consumers, but only if the buildout uses consumer welfare as the North Star and ignores narrow political or business interests. The goal of transmission reforms in Congress should be straightforward: Deliver reliable power that meets our growing needs at the lowest possible cost to end users.

In nearly every other sector — pipelines, railroads, ports, broadband — infrastructure is built when customers are willing to pay for the value it provides. Projects move forward based on contracts, price signals and risk-taking. Investors bear losses when they guess incorrectly. That discipline helps ensure that infrastructure is built to meet demand at least cost.

Electric transmission is different only because decades of poorly designed regulations — and dogged political fights over competing energy resources — have made it so. A consumer-centered approach would optimize the buildout of new transmission lines and allow competition from non-wire alternatives such as local or on-site generation of all stripes, storage, demand response, grid-enhancing technologies and microgrids.

It would allow new large customers such as data centers to pay for all required transmission upgrades if they choose to so that their costs don’t spill over to existing customers. And it would subject utility-initiated projects to real scrutiny, ensuring consumers are not locked into paying for upgrades that are not the least-cost option. Short of restructuring the entire transmission grid (again), minimizing costs to consumers is the most open-ended and market-friendly federal policy.

The consumer-first approach does not assume a particular generation mix or require sweeping national planning exercises. It rests on a more straightforward principle: Transmission should be built when it lowers the total cost of reliable electricity for consumers. FERC has long held up “reliability at least cost” as a policy goal but has brought precious little analytical expertise to the table to ensure that outcome. Adhering to the “beneficiary pays” principle and subjecting projects to rigorous cost-benefit analysis will provide better outcomes that protect ratepayers.

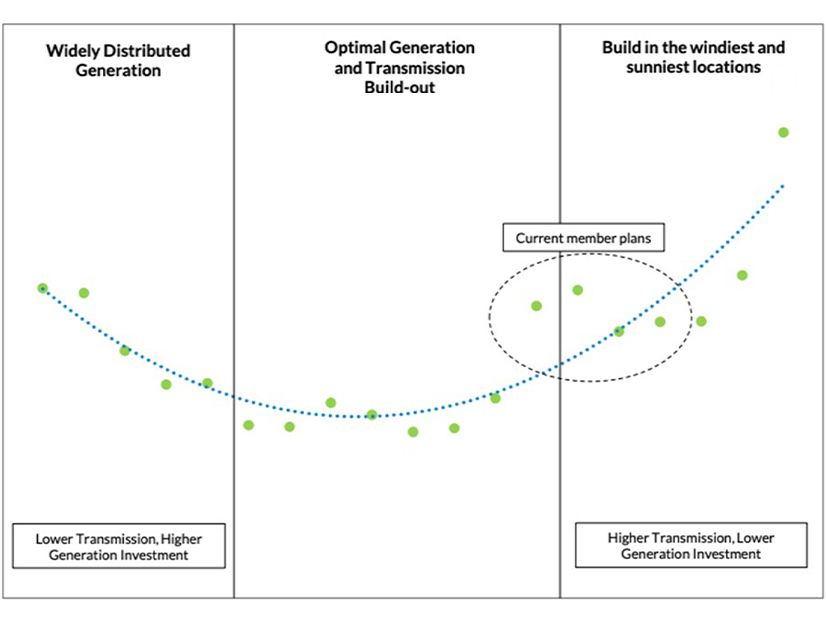

Congress should encourage transmission projects that reduce the cost of delivered power and hold FERC accountable for finding the sweet spot between too much transmission and too little. Could a FERC analysis show that smaller transmission projects are a costly short-term bandage while larger projects generate long-term savings? The “smile curve” framework introduced by MISO offers a consumer-focused approach to analyzing the role of transmission in minimizing total costs.

Transmission is a means to that end, not an end in itself. More transmission can reduce costs by connecting customers to lower-cost generation, relieving congestion or improving reliability in an economically efficient way. But more transmission also can raise bills if it is overbuilt, poorly targeted or used to inflate profits for incumbent utilities.

Today’s regulatory framework prevents complete oversight. No regulator is responsible for the full cost of electricity paid by consumers. FERC oversees wholesale markets and transmission rates. State public utility commissions typically oversee transmission siting, the distribution network, retail rates and sometimes the generation portfolio. But neither the feds nor the states are accountable for the total bill consumers pay, and decisions that look reasonable in isolation can stack up to higher costs with no one asking whether households and businesses are better off.

Transmission spending illustrates the problem. It has become one of the fastest-growing components of electricity bills, with tens of billions of dollars flowing to new projects each year. Those costs are passed directly to consumers through regulated rates, largely shielded from competition.

In PJM — the nation’s largest regional grid operator — environmental advocates note that utilities recently allocated roughly $4.4 billion in transmission upgrade costs in a single year to serve new data center demand. These costs were broadly socialized across ratepayers, even though the upgrades primarily benefited a narrow set of large loads. That is not an argument against transmission, nor is it an argument against AI-related load growth (which, according to Berkeley Lab, could help reduce rates). Instead, it is an argument against building transmission without clear accountability and under rules that fail to meet today’s moment of rapid demand growth.

The crutch of low-voltage transmission projects underscores the point. These projects are proposed unilaterally by utilities, outside the regional planning process, with limited competitive pressure and little obligation to demonstrate that they are the lowest-cost solution to a reliability problem. In PJM, spending on small ball projects such as “supplemental” upgrades has grown dramatically over time, exceeding spending on high-voltage lines that span multiple utility territories or states.

America has the capital, engineering expertise and entrepreneurial talent to build a world-class transmission system. What it lacks is a regulatory framework that consistently asks whether new investment makes electricity bills more affordable. Expanding transmission can reduce electricity costs, but catchy slogans won’t get us there. We need a consumer-first, market-disciplined approach that reliably meets today’s growth without raising electricity bills for everyday Americans.

Travis Fisher is the Director of Energy and Environmental Policy Studies at the Cato Institute and Nick Loris is the Executive Vice President of Policy at the Conservative Coalition for Climate Solutions.