Jan. 16 saw the release of a joint statement by the Trump administration and all 13 PJM governors proposing a host of new initiatives, with attendant press releases, etc. Hours later, the PJM board released its own decisional letter with directions to PJM staff. (See White House and PJM Governors Call for Backstop Capacity Auction and PJM Board of Managers Selects CIFP Proposal to Address Large Load Growth.)

The principal driver for all this is that in the most recent capacity auction, for the delivery year 2027/28, PJM cleared 145,777 MW, which was 6,517 MW less than the “reliability requirement” of 152,294 MW. This comes at a time of high capacity prices. The combination of cleared capacity shortfall and high capacity prices is seen as a crisis requiring extraordinary measures. (See PJM Capacity Auction Clears at Max Price, Falls Short of Reliability Requirement.)

There is no crisis. Industry expert Matt Estes explains in plain language what the shortfall really entails:

“First of all, people who live in the PJM region don’t need to rush out to buy home generators. Although PJM was unable to acquire all of the capacity that it said it needed to ensure reliability, this does not mean PJM will inevitably be subjected to blackouts. PJM was able to acquire significantly more capacity than it anticipates will be necessary to serve its maximum demand for the year. Instead, the shortfall affects PJM’s reserve margin, which is the amount of capacity PJM acquires above its projected peak demand. The reserve margin allows PJM to supply the peak demand even if some capacity is unavailable due to problems with equipment or for needed maintenance, and/or if demand is higher than expected.

“PJM wanted to acquire enough capacity to achieve a 20% reserve margin. Although this did not happen, PJM still acquired enough capacity to have a 14.8% reserve margin. This is a healthy margin, and close to PJM’s target reserve margin in many previous auctions. I know in the past PJM has been criticized as using overly conservative assumptions for determining its needed reserve margin. And even if a 20% margin is needed to meet its one-event-in-10 year reliability standard, there is only a 10% chance that once in 10 years circumstances will occur in the year in which PJM failed to acquire enough capacity to achieve a 20% reserve margin.”

And even if a shortage event did happen, it could be managed by rolling blackouts of short duration for a small percentage of retail customers in PJM. (This is, however, a useful reminder to utilities that they need to make sure their outage management tools, such as customer communications, are up to snuff.)

The PJM board has identified an additional option of requiring “certain large loads, including data centers, to move to their backup generators, or curtail their demand, for a limited number of hours during the year to prevent a larger scale outage for residential and other consumers.” There was 13,000 MW of projected data center demand in the load forecast for the 2027/28 auction (along with 4,000 MW of existing data center demand).

Now let’s look at why the shortfall occurred. According to PJM, there was a 5,249.9-MW increase in forecast load, mostly due to additional large loads (i.e., data centers).

It now appears the forecast demand increase was overstated. PJM’s most recent load forecast shows a 3,735-MW reduction in the forecast for the 2027/28 delivery year “due to updates to the electric vehicle and economic forecasts as well as improved vetting of requested adjustments for data centers and large loads.”

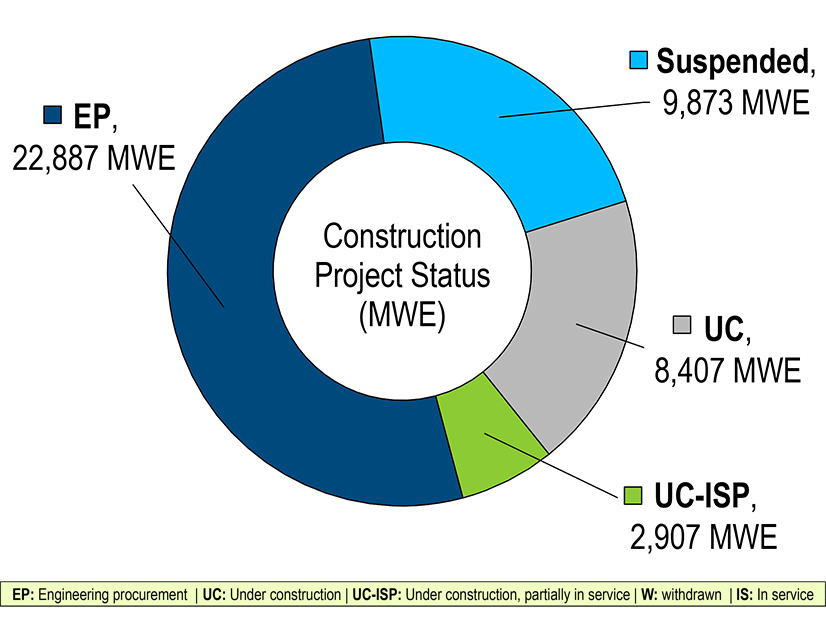

In other implications for the future, there is a large amount of new generation in various stages of development, some portion of which will go into service and offer in future auctions. The current state of resource planning is described here.

Newly available generation can be procured for the 2027/28 delivery year in the incremental auction to be held in February 2027.

In summary, the shortfall did not portend an emergency, the shortfall was overstated, and there is an abundance of potential new supply.

With this knowledge, let’s consider the Trump-governors proposal for a “Reliability Backstop Auction to procure new capacity resources commencing no later than September 2026.” Where is this new capacity coming from so quickly? In the last auction there was only 810 MW of eligible supply available that did not clear, due to the temporary price cap.

And, in complete contradiction to acquiring even this small amount of new capacity, the proposal also calls for extending the temporary price cap.

And how would this backstop auction differ from the next regular auction coming up in July? Would the price cap not apply to the backstop auction? My head hurts.

And what about all the new generating plants in various stages of development? Will they be able to offer into the backstop auction when they otherwise would offer into the regular auctions? If so, the available future supply for existing PJM customers would be reduced, creating upward price pressure in the regular auctions. And if not, where will supply for the backstop auction come from? Brand new generating projects taking years to go from conception to in-service? My head hurts.

And who are the buyer(s) of the reported $15 billion in generation? Some reports suggest it’s the data centers themselves, while others suggest it’s PJM, which would pass the costs through to load-serving entities with the states directing how the LSEs allocate the costs. My head hurts.

OK, I’ll stop here.

P.S. Except to flag this repeated claim in the Trump administration’s so-called “fact sheet”: “PJM forced nearly 17 GW of reliable baseload power generation offline during the Biden years.” This is completely false.

As everyone connected with PJM knows, PJM hasn’t forced a single gigawatt of baseload generation offline. PJM doesn’t have the power to do that, even if it wanted to. And it’s exhibited no want to do so. Instead, PJM for years has expressed reliability concerns about the retirement of baseload power plants, such as here and here.

OK, this time I’ll really stop.

Columnist Steve Huntoon, a former president of the Energy Bar Association, practiced energy law for more than 30 years.