Clockwise from top left: Mary Usovicz, Merrimac, Mass. Municipal Light Plant; Claire Thornhill, Frontier Economics; Scott Shields, New Energy Development; and Brian Jones, ERM

| NECAThe Northeast U.S. could meet its winter peak power needs with LNG or even hydrogen-fired gas turbine generation rather than relying on oil or firing up idle coal plants, argues a Houston-based entrepreneur who views hydrogen as gradually augmenting and, in some areas, supplanting fossil natural gas.

Hydrogen “fits into New England and East Coast fundamentals,” argued Scott Shields, a founding partner of the New Energy Development and a participant last week in a webinar produced by the Northeast Energy and Commerce Association.

Shields said his company began in New England, providing LNG to “peak-shaving” turbine power plants, which typically operate only a few days a year to meet peak demand. Because the gas pipeline system in the region is inadequate, he said, such turbines are often oil-fired. But given the infrequent use, the turbines can run on LNG stored on-site, he said.

But “we found that LNG wasn’t good enough. It had to be sustainable LNG; it had to have a green focus; and hydrogen fit right into that,” he said.

The company today is expanding to partner with client companies on projects that begin with electrolysis to produce green hydrogen for liquefaction or immediate injection into pipelines for power plant consumption.

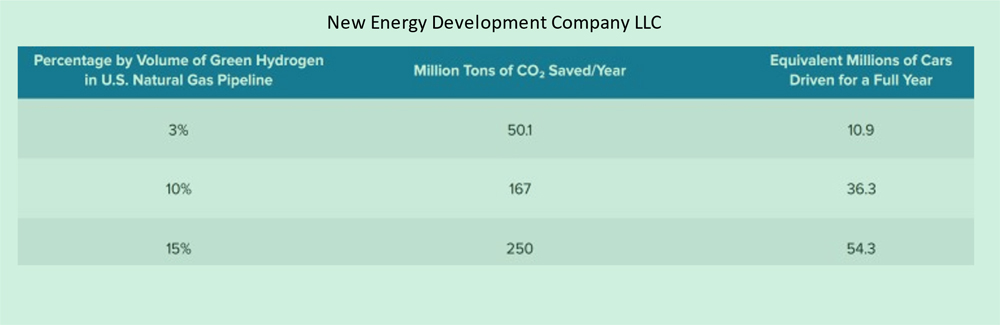

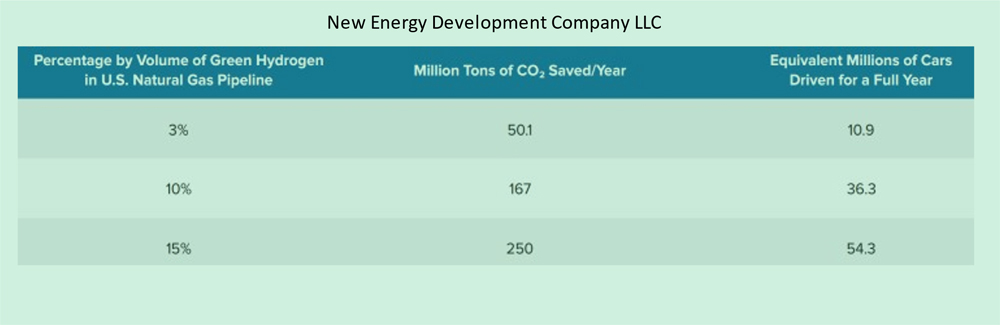

Small amounts of green hydrogen injected into gas transmission lines today would cut millions of tons of CO2 emissions equivalent to the carbon pollution created by millions of cars annually, argues Scott Shields, a founding partner of Houston-based New Energy Development Company and participant in a Northeast Energy Commerce Assn. webinar this week. | New Energy Development Co.

Small amounts of green hydrogen injected into gas transmission lines today would cut millions of tons of CO2 emissions equivalent to the carbon pollution created by millions of cars annually, argues Scott Shields, a founding partner of Houston-based New Energy Development Company and participant in a Northeast Energy Commerce Assn. webinar this week. | New Energy Development Co.

Shields argued that the future of hydrogen in the U.S. is blending with natural gas. “There’s not a [gas] turbine on the planet that can’t burn a blend of 15% hydrogen right now,” he said, adding that at that level, “we are making a huge dent in the carbon footprint of North America.”

But building gas pipeline infrastructure is difficult. Shields said the number of gas pipeline projects that have had to be scuttled because of public opposition and legal challenges has “created an opening for other fuels that otherwise wouldn’t be competitive”; in other words, green hydrogen.

“We are finding that green hydrogen is a unique substitution that goes hand in hand with LNG. Does New England need green hydrogen or LNG?” He said it does because during times of peak demand, the region must turn to oil and coal plants, totaling nearly 13 MW of capacity.

From a national perspective, he said gas-fired generation has grown, surpassing coal in 2008, but that hydrogen will gradually supplant gas, especially as green hydrogen production ramps up.

“The biggest surprise is the hydrogen use right now,” he said. “There is 13 Bcf of hydrogen produced every day. The U.S. has about 300,000 miles of natural gas pipelines — not counting the [local] distribution systems — but only 1,600 miles of dedicated hydrogen pipelines. …

“Is there going to be a flip of a switch and hydrogen is going to supplant natural gas? Absolutely not. That’s not how anything happens,” he said.

The Biden administration’s efforts to jumpstart the development of hydrogen hubs, he added, will help the growth, but that in general, hydrogen would grow with the right tax policies; “letting capital allocate to the most realistic and most cost-efficient areas would make the most sense.”

“It makes sense for hydrogen to supplant some of the most expensive natural gas markets where you cannot build pipelines,” he said, adding that by his company’s count, there are now 520 large hydrogen projects being planned across the nation.

Brian Jones, a partner at Boston-based Environmental Resources Management, said the administration’s hydrogen hub projects, funded by $8 billion allocated in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, is driving interest in hydrogen as the program calls for developments producing 50 to 100 metric tons of clean hydrogen per day.

He said the arguments over what constitutes “clean” hydrogen will likely come down to the carbon intensity of the method used to produce the hydrogen.

“There’s really a lot of focus from other stakeholders on what the emissions footprint looks like from that production process for hydrogen and then its uses,” he said. “Fuel cell-based technologies at the end-use can enable zero emissions in a bunch of different sectors, whether it be transportation, stationary remote power or portable power applications.”

Jones too said blending hydrogen into natural gas will likely occur, as well as the development of 100% hydrogen-capable gas turbines, enabling power producers to integrate intermittent renewable technologies with combustion generation.

“Clearly, there needs to be linkages between the renewable energy resources so we have a responsive fleet that can balance the intermittency of renewables as we get into a higher penetration in the future.

“When that day comes, we cannot rely solely on unabated natural gas, and so companies are looking at pilots and blending processes and even working towards 100% power generation from hydrogen and … then blending [hydrogen] into pipelines to repurpose existing assets,” he said.

At this point, however, the U.S. hydrogen strategy appears to be well behind European goals, particularly those of the U.K., the Netherlands and Germany, said Claire Thornhill, associate director at Frontier Economics, based in London.

“Europe has set really ambitious targets for the carbon hydrogen at the EU level, and the aim is to have 40 GW of renewable hydrogen in place by 2030. In the U.K., the aim is to have 10 GW of low-carbon hydrogen in place by 2030, and 5 GW of that should be electrolytic,” she said.

“At the end of 2021, there was a total of just 180 MW of installed capacity across Europe and the U.K. of green hydrogen.”