Severely behind on meeting its goal of having 600 MW of energy storage in place by 2021, New Jersey is slowly focusing on how to stimulate development to handle its ambitious offshore wind, solar and electric vehicle policies.

Gov. Phil Murphy’s 2019 Energy Master Plan set the 600-MW goal and directed New Jersey to plan for 2,000 MW of storage in place by 2030. Yet the state at present has only 500 MW “installed or in the pipeline,” according to the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities (BPU). And most of that has been in place for decades.

Storage is key to managing the electricity supply in the clean energy era. It ensures that when the wind blows and the sun shines, the state can create a store of electricity ready to be tapped when the wind stops or there is no available sun energy, such as at night or when the sky is cloud covered.

Without storage, that extra electricity would likely have to come from fossil-fueled peaker plants, which are dirty and expensive and undercut carbon reduction efforts.

“Energy storage is probably the single most important clean energy technology that we don’t talk enough about, and we don’t invest enough in,” Doug O’Malley, director of Environment New Jersey, told a recent hearing of the Senate Energy and Environment Committee. “It’s been kind of an afterthought in our state policy,” he said in a later interview.

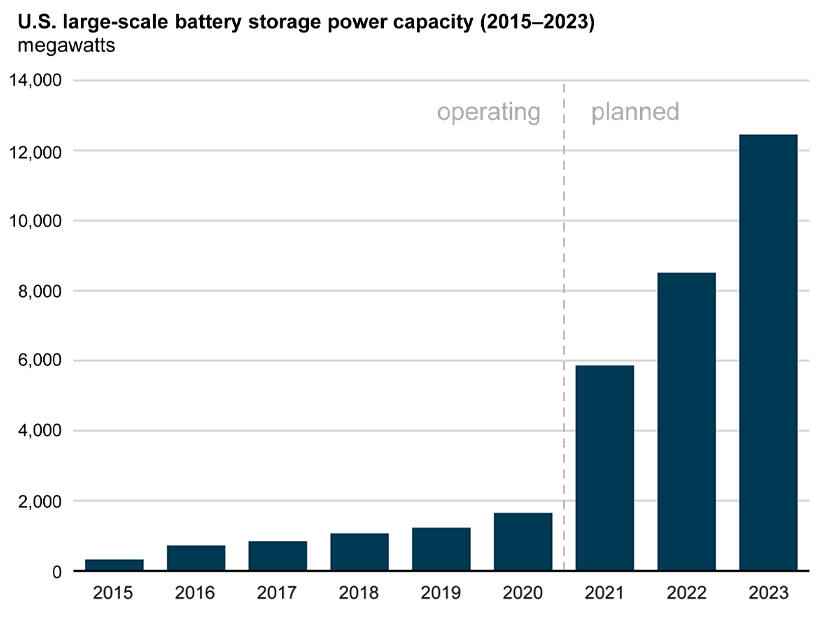

Other states have made more progress than New Jersey. The large-scale storage capacity of the U.S. as a whole grew about 35%, to about 1,800 MW, in 2020 and has tripled in the last five years, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. And utilities have reported plans to install 10,000 MW of power from 2021 to 2023. The pacesetters include New York, which released a report this year that says it is closing in on one of its goals: to create 1,500 MW of storage by 2025. And California, considered by some in the industry to be the most advanced state for storage, said in December that it has 2,500 MW in place and is close to reaching its storage goal for 2030.

Yet, there are signs that New Jersey’s relative inactivity may be changing. The Senate E&E Committee on June 9 backed a bill, S2185, that would require the BPU to develop a $60 million/year pilot program providing incentives for the installation of new energy storage systems in the state. The bill would require the BPU to adopt rules for a permanent storage incentive program no more than three years after the bill is enacted.

The pilot would offer upfront incentives based on the installed capacity of the storage that would account for up to 40% of the designated funds. It also would include a performance incentive based on how much it improves the efficiency of the grid and helps reduce peak demand.

The goal of the pilot, according to the bill, would be to provide “increased stability [for] the power supply, smoother integration of renewable energy sources, a reduction in the peak demand placed on centralized power plants and cost savings.”

Incentives for Grid Storage

In a separate initiative, the BPU is looking to incentivize the development of storage through the Competitive Solar Incentive (CSI) program, which provides subsidies for large-scale solar projects. And the BPU is developing a second phase of the storage proposals and expects to release them in a straw proposal in the second half of 2022, BPU spokesman Peter Peretzman said.

“Energy storage remains a priority of the board,” he said.

Part of the Successor Solar Incentive (SuSI) program approved by the BPU in July, the CSI program sets incentive levels for developers of solar projects above 5 MW through a competitive process, rather than the BPU setting the level.

The straw proposal, which stakeholders discussed at a May 26 BPU hearing, recommends that developers submitting a solar and storage project first compete for an incentive on the generation project alone. The developer seeking to develop storage would then submit a “storage adder” price in a second bid. (See Proposed NJ Solar REC Program Wins Initial Support.)

“Adding storage to a solar project carries some benefits that can result in increased project revenues over time,” the proposal states. “Solar projects that include storage can benefit from increased capacity ratings in PJM wholesale markets and from being able to store energy produced when local wholesale prices are low and sell when those prices are higher.”

The proposal also noted that “New Jersey does not currently have an independent energy storage program,” despite the fact that the state Clean Energy Act of 2018 required the state to develop “mechanisms for achieving energy storage goals.”

Indeed, little of the state’s existing storage stems from that legislative requirement. The state’s current storage capacity mainly consists of 68 MW of lithium-ion batteries, and the remainder comes from the 420-MW Yards Creek Pumped Storage Facility in Blairstown, the BPU told RTO Insider.

Yet the Yards Creek facility was actually developed in 1965, said Sen. Bob Smith (D), who co-sponsored S2185 and is chairman of the Senate E&E Committee. He called it a “screaming scandal” that the BPU includes the facility in its calculation of storage capacity.

“Come on BPU, you can’t take credit for that facility as meeting the state’s energy storage needs,” he said at a May 16 committee hearing. “There should have been some significant expansion. And we’re trying with this bill to nudge them along.”

Storage Growth

Nationwide, storage continues to grow. Capacity additions grew 173% in the first quarter of 2022, compared to the first quarter of 2021, according to American Clean Power. The increase was driven by the installation of 24 new battery storage projects totaling 758 MW, the organization said.

Most of the recent growth in storage capacity comes from battery energy systems co-located with or connected to solar projects, EIA said. Five states accounted for 70% of the nation’s battery storage capacity as of December 2020: California, Texas, Illinois, Massachusetts and Hawaii, with California accounting for nearly a third of the total.

CAISO said in December that it added 250 MW of storage from August 2020 to the end of 2021, at which point California had a capacity that, in the words of the ISO, was “the highest concentration of lithium-ion battery storage in the world.” The development of new storage puts the state on track to outpace the Energy Commission’s January 2021 forecast that its battery storage would reach 2,600 MW by 2030. (See California Energy Commission Updates Long-Term Forecast.)

Meanwhile, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul on June 2 announced what the state said was its largest ever land-based renewable energy procurement, with 22 solar and energy storage projects totaling 2,078 MW. (See NY Contracts More Than 2 GW in Solar and Storage Projects.)

A report released in April by the New York Public Service Commission concluded that the state by the end of 2021 “deployed, awarded or contracted” projects totaling 1,239 MW in capacity, or about 82% of the state’s target of having 1,500 MW of storage in place by 2025.

In her State of the State speech in January, Hochul doubled the state’s 2030 target of 3,000 MW. In the report supporting her proposals, the governor said the that adding storage would create a “pathway to supplant fossil-fueled generators that disproportionately affect disadvantaged communities, while ensuring a clean, reliable and resilient electric grid.”

Documenting the Storage Need

New Jersey is not unaware that it needs to advance its plans to create storage.

Speaking to the Senate Environment and Energy Committee on Feb. 10, BPU President Joseph Fiordaliso cited the topic in response to a question on what more the state should be doing to mitigate the threat of climate change.

“We have to get more involved in storage,” he said. “Storage is an expensive part of this. However, it’s one of the vehicles that’s going to make green energy work. We have to get involved with it.”

In response to a request for comment by RTO Insider on why New Jersey has not made more progress in meeting its storage goals, the BPU released a statement that said it “has taken a deliberate approach to developing energy storage programs which are an important component of our clean energy program. Although our progress to date has been deliberate, we have taken significant recent strides that will enable us to meet our goal of 2,000 MW of energy storage by 2030.”

Both Atlantic City Electric (ACE) and Public Service Electric and Gas, two of the state’s largest utilities, said they are waiting for the BPU to implement its storage plan, which will enable their own storage projects to advance. In the meantime, ACE said it expects to break ground in September on a battery storage project that will support the local grid and enhance service for customers in Beach Haven and Long Beach Island, two communities on the Jersey Shore.

PSE&G in October submitted a plan to the BPU to spend $180 million over six years to build 35 MW of storage. That plan is still pending because it has not yet received BPU approval, the company said. The project will “help us better manage power outages, reduce peak demands at substations that are under construction and allow critical facilities to maintain a reliable supply of electricity during extended power outages,” according to the company website.

The project would follow several small-scale storage projects developed by PSE&G in connection with solar projects, including one that is designed to supply power to the Department of Public Works building in Pennington and enable it to keep operating if the power goes out. The storage works in conjunction with a 158-MW solar farm at the building.

PSE&G said it also has built similar projects at the municipal wastewater treatment facility in Caldwell, Hopewell Valley Central High School in Pennington and Cooper University Medical Center in Camden.

Planning for Growth

The Clean Energy Act also required the BPU to compile a report assessing the amount of storage in the state and recommending ways to increase it. Based on that report, the board should “establish a process and mechanism for achieving the goal of 600 MW of energy storage by 2021 and 2,000 MW of energy storage by 2030.”

In part because of that ambitious goal and the state’s plan for a community solar program, the Interstate Renewable Energy Council in 2019 named New Jersey one of four states on its Clean Energy States Honor Roll for having the “most growth potential.”

Researchers at Rutgers University compiled the report required by the Clean Energy Act, and released the New Jersey Energy Storage Analysis (ESA) in May 2019. It concluded that “energy storage is an essential component of New Jersey’s sustainable energy future because it enables the grid to handle increasing amounts of clean renewable energy and manage changing, highly variable electricity demand.”

The report estimated that two technologies were cost effective and did not face excessive financial barriers: pumped hydro and thermal storage, in which energy is stored as heat and is then released when it needed. The report added that the cost of storing electricity in lithium-ion batteries, the least expensive battery storage at the time, was “dropping rapidly, but it is not currently cost-competitive for most applications.”

Meeting the state’s storage goal of 600 MW by developing battery capacity would likely require incentives totaling between $140 million to $650 million, the report concluded.

‘Variability and Balancing’

The Energy Master Plan determined that the state could meet its electricity demand by building 32 GW of in-state solar, 11 GW of offshore wind and 9 GW of storage.

“As New Jersey increases the amount of renewable generation in its energy mix, variability and balancing become critical,” the plan said. “Energy storage resources are extremely well suited to provide these services.”

The plan found that the state will need 2.5 GW of storage by 2030 and 8.7 GW by 2050. When the plan was published, New Jersey had 475 MW of existing storage — not far below the 500 MW it has now.

To promote storage development, the state at one point launched the Renewable Electric Storage Program (RESP), which lists projects initiated in 2016 and later. However, the program’s webpage has no data after Jan. 7, 2019. A report on the page shows only one storage project installed through the program, a lithium-ion battery project approved in 2017 for a $300,000 grant for Atlantic County Utilities Authority’s Wastewater Treatment Facility, which is powered by a small wind farm and a 500-kW solar project.

Program administrators also approved two other projects for funding — at a meat packer and a charter school — totaling $210,000, but it is not clear what happened. Another 15 projects were canceled, according to the page.

Asked what happened with the program, BPU spokesman Peretzman said that the “board cannot say with certainty why storage projects offered an award in the Renewable Electric Storage Program did not reach commercial operation,” and he suggested speaking to the project developers.

He added, however, that BPU staff had noted that the time when the incentive program was operating “overlapped with rules changes at PJM that made the behind-the-meter storage projects at issue in RESP less financially attractive and that likely contributed to the lack of participation.”

Storage for Home, EV, Tech Use

O’Malley, of Environment New Jersey, said the state’s failure to create storage stems in part from the BPU’s allocation of resources to other priorities.

“Obviously, we haven’t seen state investment or [the BPU] meeting the mandate set out in the Energy Master Plan,” he said. “The BPU is doing a lot. And energy storage has drawn the short stick.”

Former BPU President Jeanne Fox told the board at a hearing on the SuSI program in November that for all the impressive advances in wind and solar energy in the state “we’re behind on” energy storage. She said that homeowners such as herself and small business owners want the capability to have solar and storage projects ready to provide power if extreme weather damages the grid, and that will take an incentive program to help build capacity.

Fox, who has solar installed at her homes in Central New Jersey and the Jersey Shore, said that she lost power during Superstorm Sandy in 2012, and she wants to install storage in case it happens again.

“What you want is battery backup with that,” she said. “There will be more extreme weather events,” and storage can help mitigate the impact, she said.

James Sherman — vice president of Climate Change Mitigation Technologies (CCMT), which helps customers purchase electric trucks, buses and other vehicles — told the BPU in October that storage would be needed to support the proposed incentive program designed to generate the installation of medium- and heavy-duty EV chargers around the state for trucks and buses.

Many fleets will want a package of solar energy and storage capability to support the installation of chargers, and the cost of such a package is “impossible to know” until the BPU produces an incentive program, Sherman said.