As some data center operators plan to power their facilities with onsite generation, one researcher suggested it might be better to get electricity from the grid instead.

“At the end of the day, the hyperscalers do not want to be in the business of running a powerhouse on their data center property,” said David Porter, vice president of electrification and sustainability at the Electric Power Research Institute. “What they really want long-term is a reliable and resilient power supply. And that doesn’t come from any better place than the grid.”

Porter’s comments came during a California Energy Commission workshop Feb. 26 on California’s economic outlook, including data center growth. The workshop is part of the CEC’s 2025 Integrated Energy Policy Report (IEPR) process.

Even if a data center had small modular reactors or a combined cycle turbine on site, Porter said, operators would have to contend with maintenance, refueling and repairs.

“And it’s not a great equation for anybody that is connected to the grid to have the grid operator provide only backup service in times of extreme need and have to hold capacity back in their planning processes for some of those rare-type conditions,” he added.

An issue for data centers is that the energy-intensive facilities can be built relatively quickly but may need to wait for capacity or transmission infrastructure.

Helen Kou, a global research lead on data centers at BloombergNEF, said a standard feature of data centers is a backup generation system for reliability. But grid interconnection issues are now prompting data centers to explore a broader role for onsite generation.

“As data center loads continue to scale, the exact mix of onsite generation, be it natural gas, batteries, renewables or small modular nuclear, really just ends up depending on the project timeline, local regulatory frameworks and the corporate sustainability goals of the data center facility owner,” Kou said during the CEC workshop.

Bridging the Gap

Another strategy is the use of “bridge” solutions to meet a data center’s energy needs until transmission is available.

That could mean bringing in skid-mounted generation, Porter said, or installing solar-plus-storage to temporarily serve the data center. Even after the data center connects to the grid, the solar-plus-storage could stay in place in front of the meter as a grid resource, he added.

Another hot topic for data centers is their ability to be flexible in their energy use, particularly during grid-constrained hours.

One possibility might be for a data center to tap into its backup generation system at those times, panelists said. That could create air quality issues if backup power comes from diesel generators. But other technology is available.

Panelist Kushal Patel from Energy and Environmental Economics (E3) pointed to a Microsoft data center in San Jose, Calif., that has a backup power microgrid fueled by renewable natural gas. The RNG microgrid also allows Microsoft to participate in PG&E’s Base Interruptible Program, which pays customers to reduce electricity use when energy supplies are tight.

“The kind of capability and the kind of resource may be there,” Patel said. “Are there the right kind of regulatory incentives, policies in place to be able to maximize that?”

EPRI in October announced an initiative called DCFlex, which will establish flexibility hubs for data centers to try out new strategies that boost operational and deployment flexibility, streamline grid integration, and transition backup power solutions to grid assets. (See EPRI Launches DCFlex Initiative to Help Integrate Data Centers on the Grid.)

The initiative is bringing together hyperscalers, data center developers, technology providers, utilities, ISOs and RTOs. In February, EPRI announced an expansion of the program into Europe.

Peak Load Growth

In its 2024 IEPR, the CEC projected about 3,500 MW of new data center peak load in California by 2040, on top of roughly 1,000 MW in 2024. (See CEC Ups Data Center Demand Forecast After PG&E Revisions.) Those estimates will be updated as part of the 2025 IEPR.

Southern California Edison has about 80 MW in existing data center demand and is forecasting an increase to 1,000 MW by 2045, Elliot James Dean, an SCE data science specialist, said during the CEC workshop. Uncertainty in the forecast comes from potential on-site generation, increased energy efficiency, technology advancements and market conditions in the SCE service territory.

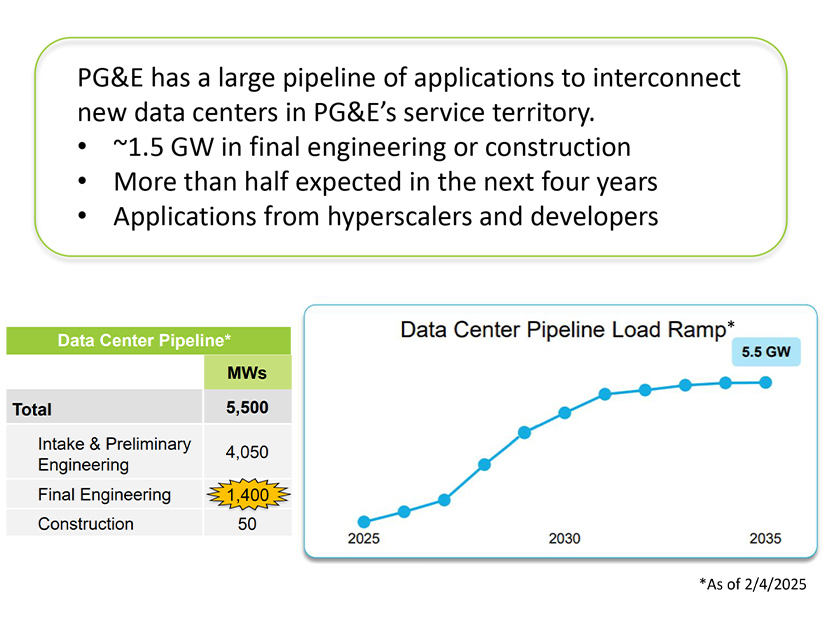

The data center pipeline in Pacific Gas and Electric’s territory totals 5,500 MW, including almost 1,500 MW in final engineering or construction, according to a workshop presentation.

One key question for utilities is how many inquiries from data centers are “real” versus an information gathering process to compare different regions. Dean said SCE has started assigning a confidence level to each project, based in part on whether it is also making inquiries elsewhere. (See Data Center Load Uncertainty Tied to Broader Economy, Google Rep Says.)

“That is not very straightforward,” Dean said. “And clear communication from the project is greatly appreciated on that piece for sure.”