The biggest issue facing FERC and the organized power markets it oversees is how they can meet rising demand reliably and affordably.

The Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on large loads from Energy Secretary Chris Wright and the co-location proceeding in PJM are both undergirded by the need to build new power plants. (See FERC Directs PJM to Issue Rules for Co-locating Generation and Load.)

“As I’ve been saying now for five years, PJM is heading for a reliability crisis, and now we’re there,” former FERC Chair Mark Christie said in an interview. “It’s no longer over the horizon. It’s right on the street with us, and the latest capacity auction results just drive home how bad the crisis is, when they fall short 6 GW of meeting the reliability requirement.” (See PJM Capacity Auction Clears at Max Price, Falls Short of Reliability Requirement.)

The primary driver for that crisis is the demand from new data centers, which has so far not been met with new generation to match it, he added.

“Really the problem is financing more than anything else,” Christie said. “We’re not getting large baseload generation built. We’re not getting combined cycle gas, which is the baseload generator of choice.”

Coal plants are not feasible at this point, and nuclear is not going to be ready at scale in time to meet the demand from data centers plugging into the grid soon, Christie said. Wind and solar, which dominate the queue, add much needed electricity to the grid, but they cannot be counted on to serve demand from data centers that want 99.999% reliable power, he said.

Christie’s home state of Virginia is a major contributor to the issue because it is home to the largest data center market in the world, Data Center Alley, and has contributed to the demand growth recently by plugging in new facilities that are ultimately served by imports from elsewhere in PJM.

“The Dominion zone was a big contributor to the deficit,” he added. “And we’re going to see whether the new governor and the new legislature are going to take action to try to get large baseload generation built.”

The supplies being added to the grid are either wind and solar or combustion turbines, and Christie is skeptical that the market on its own can add new baseload plants.

“I don’t know how high prices have to go to get large baseload generation built, but politically, you’re already getting a huge backlash because we’ve hit three all-time highs in the capacity market,” Christie said. “And we’re not getting large baseload generation announced.”

Virginia is one of the vertically integrated states in PJM, which means its political establishment needs to support the construction of new baseload, Christie argued.

“When I was on the Virginia commission, we approved four combined cycle natural gas generation units for Dominion, and every one of them got built,” Christie said. “Every one of them was ratebased, but the political leadership was supportive.”

PJM sits on top of huge supplies of natural gas in the Marcellus and Utica shale fields, which could power a new wave of combined cycle units.

“In the deregulated states, where they do not allow utilities to own generation, the question becomes: Who is going to build the large new combined cycle gas?” Christie said. “Are the [independent power producers] going to build it? We haven’t seen announcements of that.”

When states restructured their industries a quarter-century ago, PJM had excess supply, and the generators in those states were forced to sink or swim in the market, Christie recalled. Many sank, and it brought the reserve margins down for demand growth to return in a way no one expected.

“Now we’re in a perfect storm that, frankly, at the beginning of capacity market 20 years ago, nobody saw,” Christie said. “Nobody saw the explosion of demand coming from data centers 20 years ago.”

The capacity market was put in place at a time of wide reserve margins and slow, steady load growth. Ultimately, Christie thinks the states will have to address the issue on both sides of the supply and demand equation.

“The answer is really at the state level, not FERC,” Christie said. “The states have to deal with the demand side, with how they interconnect these large new data centers, and the states have got to deal with the supply side and getting generation built.”

Will the Market Respond?

Electric Power Supply Association CEO Todd Snitchler said the market will respond because PJM has now had three capacity auctions in the past year that have cleared at high prices.

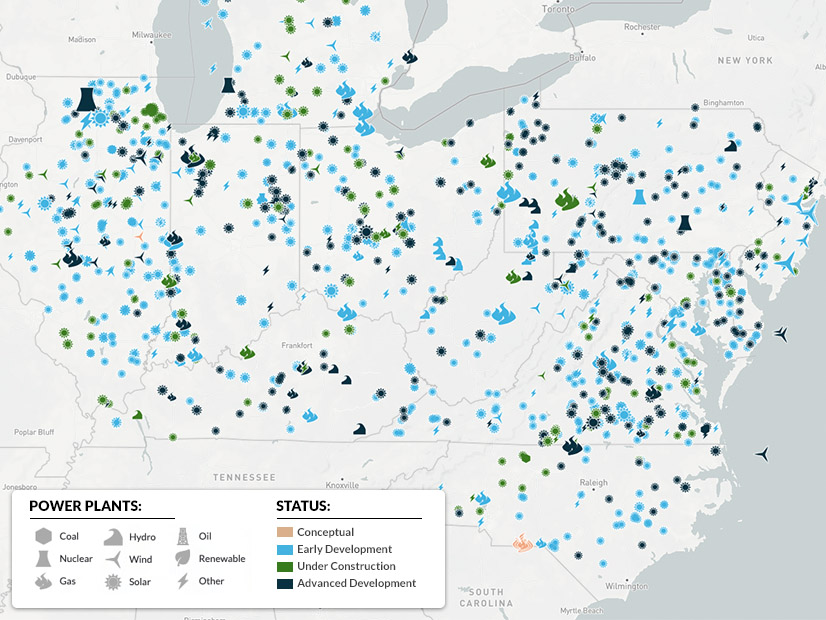

“We’ve seen almost 12,000 MW of new generation that’s expected to be added to the PJM grid between now and roughly 2030,” he said.

EPSA and a fellow IPP trade group, the PJM Power Providers, created a chart showing all the projects, including uprates and new builds, that have been committed to serve load in the market. They argued that market participants should continue responding to the higher market prices seen in the last auctions, even though they have been muted by a cap that the RTO agreed to after a complaint from Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shaprio (D). (See PJM, Shapiro Reach Agreement on Capacity Price Cap and Floor.)

“I think the compressed timeline of the auction has made it appear that the market is slower to respond,” Snitchler said. “But you know, you don’t drop a $2.5 [billion] or $3 billion investment in six months, or even maybe 12 months. And so, I think you’re going to see people who have had some time to digest the auction results lead to outcomes that are going to include that new generation that everyone wants to see.”

Before the July 2024 auction, the previous three cleared at low prices that were effectively signaling generators to retire just before the issue of meeting demands from new large loads like data centers started to become a reality, Snitchler said.

“As you see real load growth for the first time, really in probably 30 years, it’s triggering a response, and that response takes a little time to develop,” Snitchler said. “You’re already starting to see where there is incremental investment and new investment being made in PJM, but also in other parts of the country.”

The issue of rapidly rising demand leading to narrowing reserve margins is not unique to restructured markets, with vertically integrated states in MISO and SPP facing the same issues, he noted.

“It’s really a systemic issue that we’re all trying to address and resolve because everybody wants to make sure that we ensure, first and foremost, a reliable system that is also cost-effective and affordable,” Snitchler said. “I mean, if those two tenets aren’t met, then the rest of this is academic. We have to be sure that we’re meeting those two objectives.”

The load growth the industry is facing is different from that of the past, which was driven by economic and population growth. The new large loads are clustering in specific submarkets like Arizona, central Ohio and Loudoun County, Va.

Data centers might have plans to ultimately consume the same amount of power as a major city, but generally they do not immediately plug into the grid seeking to consume a gigawatt.

“There’s a construction ramp where they start from zero, and then you have that first tranche where you need to power it up,” Snitchler said. “Then they add the next phase until they’re finally complete.”

That gives the industry some time to respond to the load forecasts, which Snitchler argued are overstating future demand. While the power sector has limited supply chains for components like combustion turbines, the tech industry has a limited capacity to build the advanced chips needed for artificial intelligence-related data centers springing up around the world.

“If you look at the number of chips that are available from Nvidia and the fact that they’re sold out for the next couple of years, and there’s only 60 GW of new energy demand from those chips globally, [and] if you look at what is being projected in PJM and Texas, it would require every chip that Nvidia is going to sell for the next two years and more, and that’s not how that’s going to work.”

Utilities have also issued optimistic load forecasts that reflect plans for data centers that are not going to be built, Snitchler argued. When AEP Ohio put in place a new tariff for large load customers, it saw a pipeline of 30 GW of data centers cut down to 13 GW, and it’s not clear if all those will come to fruition, he said.

“They’re clearly an effective advocacy tool if you want to secure the ability to ratebase new generation, because ‘nobody’s moving as fast as a utility could.’ … I’ve never heard anyone say [that], but that’s the story that’s being told,” Snitchler said. “Then you need to have as big a number on your load forecast as possible, because that means you’re the solution to the problem that you’re creating.”

Multiple utilities have pushed for restructured states in PJM to change their laws and allow them to ratebase new generation for the first time in 30 years, which is an idea that EPSA is opposed to, arguing it would spoil the markets its members rely on.

“I understand they have a target earnings goal that they have set for Wall Street,” Snitchler said. “But that doesn’t mean that we should reverse 30 years of policy to help them achieve it when there are more cost-effective and more efficient ways to do that, and by putting the risk where it’s been for the last 30 years on shareholders and investors of competitive power suppliers.”

The Slippery Slope of Re-regulation

Ultimately if states change the laws and guarantee rates of return for new utility-owned generation, that would cut into the revenues of market generation owned by IPPs who would eventually ask for their own guaranteed rates — unwinding markets altogether, PJM Independent Market Monitor Joe Bowring said in an interview.

“If PPL builds power plants and puts them in rate base, then all customers are paying for them,” Bowring said. “There’s nothing stopping PPL from directly working out a bilateral agreement with the data center and building a power plant for them. But that’s not what they’re asking to do. They’re asking to put in rate base and charge everybody for it, and that’s just a way of making everyone else bear the costs and risks of the data center load.”

PJM’s markets have been slow to add generation in part because of overhanging issues from the interconnection queue and unstable market design in the capacity market, Bowring said.

“The developers who were caught up in all those delays had delayed getting some of their basic milestones,” Bowring said. “They’re now trying to catch up, but they’re behind, and that’s part of the reason we haven’t seen a lot of new additions.”

On top of the lingering issues from the queue, the capacity market has seen its rules change often, and Bowring is also skeptical of how the RTO has implemented effective load-carrying capability ratings for power plants.

“If data centers want to come online quickly — which is fine, we want them to come online quickly — they should figure out how to bring their own generation,” Bowring said. “That doesn’t mean you’re turning data centers into power plant operators. You sign a bilateral contract with a developer; they build the power plant. They manage all that for you, but you have power, and that’s the quickest way to get things going, because the data centers have a huge incentive to get power quickly.”

Some of the hyper-scalers in the data center world can build their own power plants. Google parent Alphabet announced Dec. 22 that it was buying Intersect, which develops power plants for new large loads. But not every data center developer is among the largest companies in the world by market capitalization.

“The market is going to take a little while to react, and I’m hoping that in a few years that will restore equilibrium,” Bowring said. “But at the moment, as you know, we’re something like 6,600 MW short.”

While meeting new load has always been a key part of the business, the scale of the new demands from data centers is unprecedented.

“We’re talking 30[,000] to 60,000 MW of demand,” Bowring said. “That is absolutely unprecedented,” and it’s amid “a time when PJM was getting tighter for other reasons. That confluence is, I think, absolutely unique. I mean, PJM has been long for almost forever.”

The last time the PJM region faced a major shortage was decades before it was an RTO, and the power pool was dealing with the aftereffects of the accident at Three Mile Island in 1979, he added.

The issues data centers present to the grid are unique, and they need to be handled differently than load growth was in the past, Bowring said.

“The whole notion of just plugging in is naive, almost willfully naive, in some cases,” Bowring said. “I understand why the data centers imagined a few years ago [that] they could just plug into the grid and everything would be fine, but everyone knew at least a couple years ago that that was not going to work longer-term; that it was simply overwhelming the grid. So, it has to be dealt with in special and targeted ways.”