New England Power Pool stakeholders proposed changes to Forward Capacity Market (FCM) parameters and rules regarding the timing of delist bids during a marathon Markets Committee meeting Sept. 8-10.

Several of the proposed changes concerned ISO-NE consultants’ estimates of the revenue potential of wind, solar and storage resources. Others concerned the inputs for the calculation of the net cost of new entry (CONE).

The committee will vote on the parameters and proposed amendments next month, but the votes are advisory under sections 8 and 11 of the NEPOOL Participants Agreement.

Abigail Krich and Alex Worsley of Boreas Renewables presented RENEW Northeast’s critiques of the revenue figures proposed by Concentric Energy Advisors (CEA) and Mott MacDonald, two consulting firms hired by ISO-NE to update the FCM parameters for the 2025/26 capacity commitment period.

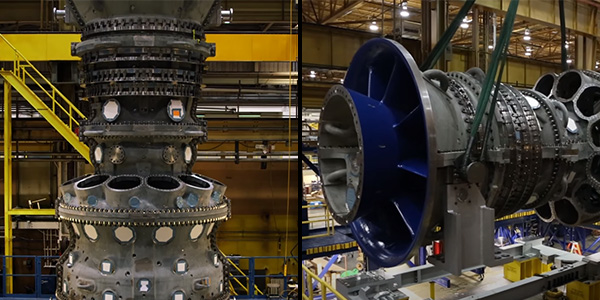

The key parameters — net cost of new entry (CONE) and offer review trigger prices (ORTPs) — can determine whether certain resources are competitive in the auction. Net CONE estimates the capacity revenue a new generator needs in in its first year of operation to make it economically viable; it is based on a “reference unit” — the most profitable commercially available generation technology for new entry in New England — currently General Electric’s 7HA.02 gas-fired combustion turbine.

ORTPs are estimates of the low end of competitive offers for other classes of technology. New supply offers above the ORTP are presumed to be competitive and not an attempt to suppress the auction clearing price. An offer below the price is subject to a unit-specific review by the Internal Market Monitor to verify the resource’s cost.

Offshore Wind

Krich told the committee Wednesday that the consultants’ estimates of offshore wind costs are “totally outside and above the range of other estimates.”

The RTO proposed using $5,876/kW (2019$) for the overnight capital cost for offshore wind, resulting in an ORTP of $32.31 to 32.51/kW-month, almost double the highest clearing prices on record and well above $2 to $7.03/kW-month range for the five auctions since 2016.

Krich said the assumption “is significantly higher than commercial expectations,” based on RENEW’s analysis of executed OSW contracts in New England and other publicly available data.

The RTO “used a bottom-up methodology for determining the capital cost assumption but has not presented cost-based benchmarking that supports any element of that analysis or the final capital cost assumption,” she said.

[Note: Although NEPOOL rules prohibit quoting speakers at meetings, those quoted in this article approved their remarks afterward to clarify their presentations.]

One reason the RTO’s estimates are too high is because its $70 million interconnection cost “does not align with cost estimates in completed ISO-NE interconnection studies for projects almost identical to the proposed project,” Krich said.

She noted that the average interconnection cost for the 13 OSW projects studied by ISO-NE is $35.5 million, with only three of the projects having costs of $70 million or more, she said.

“Choosing the highest costs for projects studied by ISO-NE is not representative of what developers will typically face and should not be used in the determination of an ORTP,” she said.

Krich also challenged the RTO’s $4.2 billion engineering, procurement and construction cost estimate for an 800-MW OSW project, saying it should be closer to $2.1 billion.

RENEW will ask stakeholders to reduce OSW’s capital cost assumption to $2,900/kW (2019$). At that cost, Krich said, OSW shows an almost $4/kW-month surplus based on its energy revenues and renewable energy credits, meaning it doesn’t need capacity revenue to cover its costs and should have an effective ORTP of $0.

“Prices have been dropping really precipitously” in the last few years, she said. “We honestly don’t understand where the higher numbers from ISO New England come from.”

Deborah Cooke, ISO-NE’s principal analyst for market development, who presented the RTO’s proposed on net CONE and ORTP calculations, declined to comment on the discrepancies between RENEW’s and the consultants’ estimates.

Operating Lifetime

Krich also challenged the RTO’s proposed 20-year asset life for all generation technologies in its ORTP model, saying lifetime expectations for wind and solar have increased beyond 20 years since the last ORTP recalculation.

“This leads to higher ORTP values, unnecessary review and potential mitigation simply because [the RTO] is not recognizing the full life expectancy of these technologies,” she said. “If certain technologies’ expected revenues beyond 20 years are being neglected in the [minimum offer price rule] implementation, the capacity auction could clear at prices higher than equilibrium.”

Battery EAS Revenues

Krich and Worsley said CEA was overly conservative in estimating batteries’ energy and ancillary service (EAS) revenues.

ISO-NE proposed using $1.87 to 2.67/kW-month (2019$) in energy and reserves revenue, which RENEW contends “underrepresents what a competent battery developer could earn in the New England markets” and fails to follow the guidelines the External Market Monitor recommended in December 2019.

RENEW proposed an ORTP value of $4.53 to 4.86/kW-month, compared to the RTO’s $4.92 to 5.78/kW-month.

Worsley said the RTO’s estimate shows no effort to optimize dispatch using available data at the time of dispatch, such as day-ahead market prices, and that its assumed charging timing is often suboptimal. It assumes no ability to respond to forecasted market conditions or to change strategies through the year, making it unable to capture daily, monthly or seasonal market changes, he said.

Using the EMM “continuous information” approach, Worsley said, the batteries would have 52% higher energy and reserve revenues than assumed by CEA. RENEW recommended the RTO adopt a more conservative calculation by the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office, which would result in a 41% increase.

“A competent [energy storage resource] owner should be assumed to use publicly available information known prior to dispatch,” he said. “These are common and not difficult to implement, and we believe [they] should have been appropriately within CEA’s scope of work.”

Ben Griffiths, an energy analyst for the attorney general, said the deterministic spreadsheet model CEA used resulted in “materially lower” EAS revenues than the basic linear optimization model he used. “It’s the wrong modeling tool for batteries,” he said of CEA’s choice.

The CEA model assumed the battery charges only during fixed windows, rather than when prices are expected to be lowest, Griffiths said. It also assumes it discharges when prices reach a fixed threshold — not adjusted for time-of-day or season — that often misses higher values later in the day. It also limited cycling to once-per-day, even if when it would be advantageous to cycle more than once, he added.

“EAS revenue estimates for ORTPs should not be based on the rosiest of predictions, but neither should they [be] based on the assumption of bumbling incompetence,” Griffiths wrote in a memo summarizing his research.

Inputs for Reference Unit Net CONE Calculation

Bruce Anderson of the New England Power Generators Association (NEPGA) identified several changes the group wants ISO-NE to make to input variables for the reference unit net CONE calculation.

Anderson called for using a historical premium on intraday gas costs during those hours when the reference peaker unit is dispatched in real time, as well as including the costs of firm gas delivery and sellback costs and imbalance charges for gas nominated but not consumed.

He also challenged the RTO’s proposal to use the lower heating value (LHV) for the nominal heat rate, saying it should use the higher heating value (HHV), on which gas prices are based. (HHV is the total heat obtained from combustion of a specified amount of fuel at 60 degrees Fahrenheit. The LHV is the HHV minus the latent heat of the water vapor formed by the combustion of the hydrogen in the fuel. HHV is typically about 11% higher than the LHV.)

NEPGA said the RTO’s proposal that the reference unit be located in New London County, Conn. — within 2 miles of both the Algonquin interstate gas pipeline and a 345-kW transmission line — is unrealistic because there are no greenfield sites permitted for industrial use that meet the criteria. It said it should extend the lateral and radial lengths to 5 miles to reflect the difficulty in finding suitable parcels.

Anderson also said the RTO improperly assumed there would be no compression or lateral upgrade costs to ensure gas delivery.

NEPGA also disputed the monetization of bonus depreciation, saying the proposed net CONE value is insufficient incentive for a sale lease back financing agreement or other tax equity financing. It also asked for a lower debt/equity ratio than the 55/45 proposed by ISO-NE to reflect merchant market risk and the inclusion of “reasonable estimates of owner’s cost and contingency,” which were omitted by the RTO.

LS Power’s Mark Spencer complained that Mott MacDonald had failed to provide information he said he had been requesting for three months regarding several of the company’s inputs and assumptions.

“We’re looking to have a vote next month, and the questions are still unanswered, so I don’t know what else to do other than to register an objection that it doesn’t seem like the information is forthcoming,” Spencer said.

Calpine’s Brett Kruse predicted the disputes over the assumptions will result in litigation before FERC and potentially federal court.

“They’re going to have to stand on their data as opposed to hiding behind the cloak of secrecy here. … My hope is that the ISO and Concentric are really riding herd on Mott MacDonald. Quite frankly, I have not been impressed with what I’ve seen from them.”

CEA’s Danielle Powers, who led its presentations on CONE and ORTP calculations, declined a request to respond to the criticism.Mott McDonald referred a request for comment to ISO-NE.

Change to Delist Bid Threshold

Sigma Consultants President Bill Fowler presented a proposal on behalf of Calpine and Vistra Energy, and Vistra’s Dynegy unit, to address the disadvantage he said is faced by resource owners having to lock in static delist bids four months before the Forward Capacity Auction.

The IMM is proposing that the dynamic delist bid threshold (DDBT) be set equal to its expectation of the next auction clearing price. All delist requests above this level must become static bids.

Fowler said locking in prices for statics is much riskier and more expensive than a dynamic bid, creating a disincentive to offer at prices only slightly above the DDBT. “Failing to recognize this will bias offers and may lead to clearing prices below competitive levels,” he said.

The lock-in means resource owners cannot account for market and regulatory changes that occur between October and February, including the installed capacity and local sourcing requirements, waiver requests, and state and federal regulatory actions, including FERC action on FCM questions, Fowler said.

Resources making static delist offers will add a risk premium to account for these costs and risks, Fowler said. If the resource’s competitive price is greater than the DDBT but less than the DDBT plus the margin, he said, resource owners are incented to not bid the competitive price, and instead bid the DDBT minus 1 cent.

“The resource owner has to hope that his offer to exit at DDBT minus 1 cent clears. If it doesn’t, the resource is stuck with a CSO [capacity supply obligation] at a price it didn’t want.”

It also means the Monitor and market will never see the true competitive offer; the resource may take on a CSO it doesn’t want; and the FCM may clear at an uncompetitive level, he added.

Fowler noted the RTO’s analysis of the new DDBT method found it misses the actual clearing price by 25%. At a $2 clearing price, a 25% margin equals 50 cents; at a $4 clearing price, it is $1.

As a result, Fowler said the DDBT should be set at a “reasonable margin” — 50 cents to $1/kW-month — above the expected clearing price. “A margin of this size would help address this inaccuracy,” he said.