2020 was a year that strained the very idea of society and tested the United States’ democratic institutions. It began with the acquittal of the president on impeachment charges and ended with his re-election defeat, seen by many as a referendum over his response to the novel coronavirus that has killed more than 350,000 people.

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the value of the Internet even as it proved that people are still as dependent on face-to-face contact and social interaction as their ancestors 300,000 years ago.

The year also brought increasing evidence of climate change: The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season was the most active in recorded history, and the Western U.S. saw record-high dry weather that once again triggered dangerous wildfires and a heat wave that drove CAISO to enact rolling blackouts in California.

An Appetite to Address Climate Change?

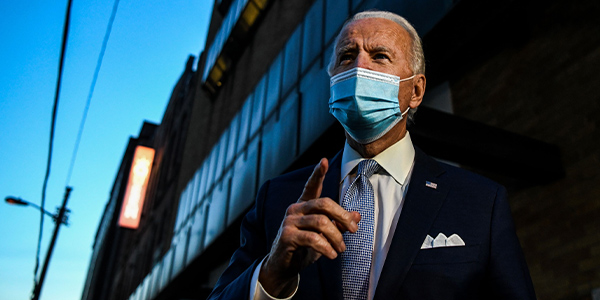

Though Joe Biden won the presidential election, Democrats did not manage to flip the Senate as they had hoped, at least not yet. That will be determined as soon as tomorrow, when Georgia holds two runoff elections for its seats, currently held by Republicans. If Democrats win, there will be a 50-50 tie in the Senate, and Vice President Kamala Harris will hold the tie breaker.

Democrats also lost seats in the House of Representatives, narrowing their majority. Thus, Democrats will lack the sort of margins that could enact Biden’s promises for sweeping climate change policies. (See GOP Senate May Limit Biden Climate Ambitions.)

In the final days of the year, the Democratic-controlled House and the Republican-controlled Senate passed the first comprehensive energy policy legislation since 2007 as part of an annual spending package. After hinting at a veto, President Trump signed the bill a week after it was passed. Among its many provisions the legislation included tax break extensions for wind, solar, energy efficiency and carbon capture; a requirement for the Interior Department to seek at least 25 GW of renewable projects on federal lands; and a phaseout of the use of hydrofluorocarbons in air conditioning and refrigeration. (See Wind, Solar, EE, CO2 Storage Win Tax Breaks.)

How much the bill will impact U.S. emissions is unclear. But the legislation will not result in the scale of decarbonization of transportation, industry and building infrastructure that experts say is necessary to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. (See Net Zero Price Tag: $2.5 Trillion.)

Another question that arose late last year is how the U.S. will rejoin the Paris Agreement on climate change after it formally withdrew just after Election Day. Biden has pledged that he would immediately begin that process after he is inaugurated, but the U.S. will need to update its emission-reductions targets from those sought by President Barack Obama in 2015. And though he has proposed spending on clean energy projects to combat climate change, Biden has not yet detailed regulations, like Obama’s Clean Power Plan, to achieve any targets under the agreement.

FERC Transition

With commissioners serving staggered five-year terms, the makeup of FERC is always in flux, and last year was no different for the agency.

Early on, Commissioner Bernard McNamee announced he would not seek another term after his current one expired June 30. While he said he would continue to serve until a replacement was confirmed, he resigned shortly after President Trump nominated his intended successor, Virginia State Corporation Commission Chair Mark Christie, in late July.

It took the Senate until Nov. 30 to confirm Christie, a Republican, and Allison Clements, a Democrat and former energy policy consultant. Clements was sworn in soon after being confirmed, and Christie was sworn in on Jan. 4, giving the Republicans a 3-2 edge. (See Senate Confirms Christie, Clements to FERC.)

Meanwhile, tension continued to grow between FERC and states, which complained that the commission’s capacity market rules were frustrating their efforts to integrate renewable resources.

But Chair Neil Chatterjee, a Kentucky native, continued his transformation from coal-state partisan by shepherding through Order 2222, which ordered RTOs and ISOs to open their markets to distributed energy resource aggregations. (See FERC Opens RTO Markets to DER Aggregation.) He also held a technical conference on integrating offshore wind and supported a policy statement inviting states to propose carbon pricing in the wholesale markets.

Chatterjee acknowledged that these actions likely led Trump to demote him and name Commissioner James Danly — who was confirmed in late March after serving as FERC’s general counsel — as chair. (See Trump Names Danly FERC Chair.)

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, if Danly is replaced immediately after Inauguration Day he will be the only chair to have never presided over an in-person open meeting. The commission moved its January meeting to the day before Biden will become president, ensuring at least one more virtual session for Danly and the Republican majority. Biden will name either Clements or her Democratic colleague Richard Glick (the more likely candidate) as chair.

How long the Republicans will maintain their majority will depend on Danly. Chatterjee’s term ends June 30, though he can stay on after that until a replacement is confirmed or Congress adjourns for the year, and he has pledged repeatedly to serve out his term.

It is also possible that Danly could resign — as Republican Chair Joseph T. Kelliher did when Obama assumed the presidency in 2009 — allowing Biden to fill his seat with a Democrat. That would give the Democrats a 3-2 edge and could allow Biden to renominate Chatterjee.