The panel discussion on green hydrogen at the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners’ Winter Policy Summit last week hit many of the same themes sounded at the organization’s summer conference. Speakers at both events touted the potential of the emissions-free technology to provide days or even weeks of power while acknowledging the challenge of scaling the still-expensive process of using renewable energy to produce hydrogen from water. (See NARUC Panel: ‘Green’ Hydrogen Could Lower GHGs.)

What appears to have changed in the last six months is the level of energy industry buy-in, as evidenced by the Electric Power Research Institute’s recently launched Low-Carbon Resources Initiative, which CEO Arshad Mansoor said was able to quickly raise $100 million from corporate sponsors for research on hydrogen and other low- and no-carbon fuels.

NextEra Energy’s Florida Power & Light generated plenty of industry buzz last July with the announcement that it would build a 20-MW electrolyzer to produce green hydrogen that would be mixed with natural gas to run a 1.75-GW combined cycle plant. (See NextEra Dips its Toe in Hydrogen Energy.)

Despite the positive press, Matt Valle, vice president of development for FPL, cautioned that while green hydrogen “seems like a silver bullet, it may not be.”

“Think about the technological advances that are going on in lithium-ion batteries right now,” Valle said at the NARUC session on Feb 10. “You have solid state; you have longer-duration and flow batteries. It’s certainly not the only thing out there that could help decarbonize the economy. There’s a lot of hype right now, and you have to separate it.”

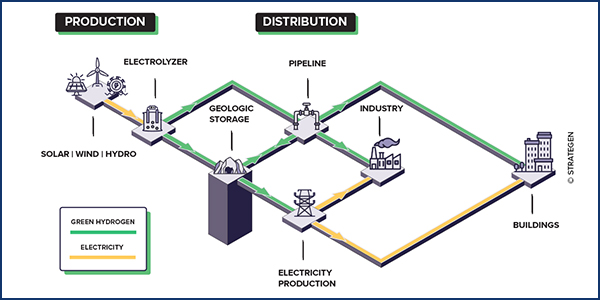

Utilities’ excitement about green hydrogen is linked not only to its ability to store energy for long durations, Valle said. It’s also about the technology’s potential to repurpose fossil fuel plants and natural gas pipelines that might otherwise become stranded assets.

Another major green hydrogen project in development, the Intermountain project in Utah, aims to recommission a former coal plant to initially burn a mix of hydrogen and natural gas, with the goal of running 100% on green hydrogen by 2045. Hydrogen produced for the plant will be stockpiled nearby in a natural salt cavern capable of keeping 150,000 MWh of power on tap, according to the nonprofit Green Hydrogen Coalition.

For Laura Nelson, executive director of the coalition, the rising interest in green hydrogen signals a critical expansion of the net-zero discussion. “When we talk about this 100% clean energy future, that means different things to different folks,” Nelson said. “The carbon neutrality goals are not going to be completely met with renewable energy and battery storage. We have this rapidly transforming energy system, and you’re going to need a robust portfolio mix.”

Nelson, Valle and Mansoor all pointed to green hydrogen as a bridge for decarbonizing industries that are hard to electrify.

“In order to get to the net-zero world, the most important opportunity is actually not in the electric sector; it’s in the industrial sector,” Mansoor said. “If you are in the chemical industry, if you are a petroleum company, if you are a plastics manufacturer, you’re not using petroleum; you’re not using natural gas in the future. You could be using hydrogen.”

“I typically don’t talk to chemical plants or steel plants or heavy-duty trucking,” Valle added. “What if I had hydrogen to potentially sell to those customers in the future? Not to necessarily say it has to be utilities, but somebody is going to have to generate a lot of green hydrogen. That is going to play a major role in decarbonizing the U.S. economy over time.”

New Technology, New Infrastructure

Hydrogen gas, produced from a natural gas feedstock, is already used around the globe for industrial processes such as oil refining, methanol production and ammonia production for fertilizers. But, according to the Green Hydrogen Guidebook produced by the GHC, as of 2019, green hydrogen represented 0.1% of global hydrogen production, with $365 million invested in 94 MW of capacity.

Pilot projects are a first step toward commercialization. But ongoing research and investment ― like EPRI’s Low-Carbon Resources Initiative ― are needed to whittle down costs and address other key issues about the technology. To produce hydrogen without carbon emissions, excess wind and solar energy are used to power an electrolyzer that splits water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. The hydrogen gas can then be stored, for example, in a fuel cell or run through a turbine to produce electricity.

The GHC guidebook pegs the current cost of producing hydrogen via clean-energy electrolysis at $1,200/kWh. But, as the technology scales, prices could drop 90%, to between $115 and $135/kWh by 2030, according to the guidebook.

Nelson also stressed the importance of integrating green hydrogen into resource planning and wholesale markets.

“Regulation can be important for creating markets, and that’s what has to happen,” she said. “Market rules really have to allow green hydrogen to be an eligible technology. It is going to be critical to see an evolution of this resource to provide services in the energy storage, resiliency and reliability space.”

On the logistics side, storing and transporting hydrogen requires considering its difference from fossil fuels: Specifically, as the second lightest element on Earth, hydrogen takes up a lot more space. It is not “a one-on-one replacement for either petroleum or natural gas,” EPRI’s Mansoor said. “If you have one can of natural gas, you would need three cans of hydrogen.”

Valle points to efficiency as another key issue: Too much energy is lost in the process of making green hydrogen and then converting it back into electricity.

Converting renewable power to hydrogen, “you lose 30% or so of the energy,” he said. “When you take the hydrogen and run it through a combined cycle [plant], which has its own efficiency losses, you’re down to 50%. Hydrogen is not going to win head-to-head against the battery today.”

Still another problem is embrittlement, the weakening of metal infrastructure that may occur because of the hydrogen atom’s small size and ability to interact with metals and plastics. Whether natural gas pipelines could be used for 100% hydrogen remains a question, one that could lead to more regional production and consumption, said panelist Llewellyn King, host of the public affairs series “White House Chronicles.”

“Every new technology, every new material produces its own infrastructure” and generates its own innovation, King said.

“What information we have around testing and pipeline integrity is going to be important,” Nelson agreed. “How we construct and build that new infrastructure is going to be a function of how this particular commodity and the economy for this commodity emerge.”