By Michael Brooks

Climate change could have catastrophic effects sooner than previously thought and preventing them will require cooperation on an unprecedented global scale, according to a new report by the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

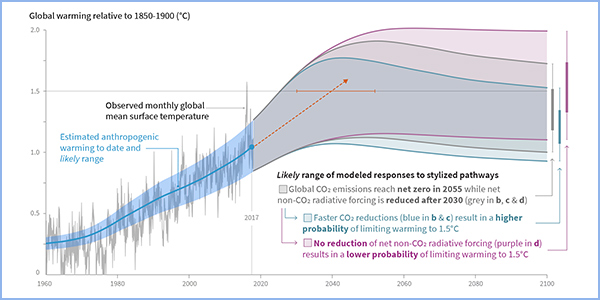

The study, released on Sunday from Incheon, South Korea, examined the effects of a 1.5-degree Celsius (2.7-degree Fahrenheit) increase in the global average temperature from 1850-1900 levels. If the current rate of global warming continues, the average temperature would hit 1.5 C by 2040, according to the report.

“It’s like a deafening, piercing smoke alarm going off in the kitchen. We have to put out the fire,” The Washington Post quoted Erik Solheim, executive director of the U.N. Environment Program. He said the world must either stop carbon emissions entirely by 2050 or find some way to remove them. “Net zero must be the new global mantra.”

The report estimates that temperatures have increased by about 1 C (1.8 F) so far, and that the impacts of that increase are already being felt in increased storm intensity, precipitation, wildfires and heat waves; rising sea levels from melting polar ice; and the nearing extinction of several species, including coral. Such impacts could disrupt the global food supply chain and cause mass migration and increased poverty, the report says.

“Extra warming on top of the ~1 degree C we have seen so far would amplify the risks and associated impacts, with implications for the world and its inhabitants,” the IPCC said in a FAQ. “This would be the case even if the total warming is held at 1.5 degrees C, just half a degree above where we are now, and would be further amplified at 2 degrees C global warming.”

The report is a result of a provision in the 2015 Paris Agreement, which saw 195 countries, including the U.S., agree to reduce their carbon dioxide emissions by 26% from 2005 levels by 2025 to prevent a 2-degree Celsius (3.6-degree Fahrenheit) increase. It was added at the request of small island nations in the tropics, which wanted the effects of a 1.5-degree increase to be studied, as they are more susceptible to rising sea levels.

To prevent a 1.5-degree increase, global CO2 emissions would need to be reduced by 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 and 100% by 2050, according to the report. This is still possible, the authors say, but it would require a massive undertaking by the entire world.

“The speed and scale of transitions and of technological change required to limit warming to 1.5 degrees C has been observed in the past within specific sectors and technologies,” the report says. “But the geographical and economic scales at which the required rates of change in the energy, land, urban, infrastructure and industrial systems would need to take place are larger and have no documented historic precedent.”

For the electricity industry, this means dramatically reducing the use of coal and increasing the use of renewable resources for generation. This is true under every scenario, or “pathway,” studied by the report’s authors.

Coal’s share of the resource mix would need to drop to 1 to 7% by 2050, compared to 40% now, and only if large-scale carbon capture and sequestration technology is developed by then. Natural gas-fired generation would also have to be reduced by as much as 60% (though it could increase with the use of CCS), and renewables’ share would need to increase to as much as two-thirds.

The report is less sure about nuclear power. Under some scenarios global nuclear capacity increases, while it decreases in others. The report attributes this to the high cost of building nuclear plants and political opposition stemming from perceived safety risks. While some countries may elect to rely on nuclear for emission-free power, it may not be feasible for developing countries, the researchers said.

President Trump in June 2017 announced he intended to withdraw the U.S. from the Paris Agreement. The earliest the country can do so is Nov. 4, 2020. (See Trump Pulling U.S. Out of Paris Climate Accord.)