By Michael Brooks

PJM stakeholders last week dug in further on the RTO’s proposed revamp to its capacity market, reiterating comments made last month in FERC’s paper hearing on the proposal (EL16-49, ER18-1314, EL18-178).

In reply comments Nov. 6, PJM rebutted “anticipated” criticisms of its Extended Resource Carve-out (RCO) proposal, which would allow specific, state-subsidized resources to opt out of the capacity market and the RTO to adjust market clearing prices as if the resources were still in.

PJM’s proposal is a response to the Fixed Resource Requirement (FRR) Alternative FERC recommended when it found the RTO’s minimum offer price rule (MOPR) unjust in June. PJM’s current FRR only allows utilities to opt out of the market if they can serve all of their load through other means, such as bilateral contracts.

“Despite the hundreds of pages of initial comments, barely a handful provided the commission with detailed proposals supported by pro forma tariff changes,” PJM said. “Of those that did, only PJM’s proposal meets both key objectives, i.e., preserving competitive markets while accommodating state policies.” (See Little Common Ground in PJM Capacity Revamp Filings.)

Critics generally fell into two camps. One argued for a rejection of any carve-out, calling instead for a “clean,” MOPR-only construct that extended to all resources. The other generally supported the concept of the FRR Alternative but argued that because of the repricing mechanism, Extended RCO would lead to inflated capacity prices.

Exelon said the FRR Alternative “strikes a just and reasonable balance among equally important policy goals. It makes room for states to pursue energy policy initiatives favoring particular types of generation resources, by allowing states to provide for the procurement of their capacity outside the PJM auction market — but credits load for that capacity, thus avoiding unnecessary costs for customers.”

Exelon said “the Extended RCO results in … massively inflated customer costs because of a fatal design flaw: PJM proposes to set the stage 2 price — which cleared resources would be paid — by removing RCO resources from the supply curve entirely. In other words, rather than resetting the bids of RCO resources to ‘competitive’ levels at stage 2, as the MOPR purports to do, the Extended RCO simply acts as though the RCO resources do not exist. That makes no sense.”

The Maryland Public Service Commission, which also argued that Extended RCO would lead to inflated clearing prices, proposed a separate auction for state-subsidized resources.

“Resources that do not clear the auction but serve to set a higher clearing price would be paid what PJM terms as ‘infra-marginal rent payments,’” the PSC said. “These potentially perpetual payments, in the form of uplift, are characterized as rents those resources would have ‘earned’ had they cleared the auction at the elevated artificial clearing price.”

FirstEnergy Solutions called Extended RCO “a reasonable means of accomplishing the objectives articulated by the commission.” But it also criticized PJM’s proposal to continue applying the MOPR to previously subsidized resources seeking to re-enter the capacity market. “The commission should consider the reality of this proposal: Most resources that elect the [resource-specific FRR] for some period of time would effectively be precluded from ever re-entering” the capacity market, FES said.

Exelon also joined in a reply brief in support of the FRR Alternative filed by a diverse group of stakeholders: the Nuclear Energy Institute, the Illinois Citizens Utility Board, the Natural Resources Defense Council, Talen Energy, the Sierra Club, PSEG Energy Resources & Trade and the D.C. Office of the People’s Counsel.

Noting that they frequently disagree on other issues, the groups said, “We are unified, however, in our belief that the commission and PJM must reasonably accommodate states taking actions to achieve their clean energy policies. …

“The only parties arguing against the concept of balancing an expanded MOPR with adoption of a resource-specific FRR mechanism are the companies that have brought — and lost — legal challenges to the states’ authority to implement clean energy programs.”

Clean MOPR

The Electric Power Supply Association, the PJM Power Providers Group and NRG Power Marketing continued to insist on a clean MOPR, in which all resources, with limited exceptions, are subject to the rule. They also criticized FERC’s FRR Alternative proposal.

“As acknowledged by PJM and others advocating such an approach, the FRR Alternative will negate the remedial benefits of an expanded MOPR and thus perpetuate the price suppression problem that the commission properly found to be unjust and unreasonable in the June 29 order,” EPSA said. “Adopting such a replacement rate would be irrational and unacceptable as a policy matter and unlawful as a statutory and constitutional matter.”

“Let’s call FRR-A what it is: a proposal to reregulate a substantial portion of the competitive wholesale market,” NRG said. “Adopting FRR-A would signal a retreat from the competitive markets that the commission has espoused since its landmark Order No. 888. Like all massive government interventions in the market, FRR-A would stifle the efficient allocation of private capital, shift costs and risks to consumers, and replace private, at-risk investment with ratepayer-backed investment.”

EPSA criticized Exelon, whose nuclear plants in Illinois are the beneficiaries of zero-emission credits, for calling for a blanket waiver of FERC’s affiliate transaction rules in espousing the right of states to choose how they procure energy. In its initial brief, Exelon had said, “At the very least, the commission should treat state involvement in the procurement of capacity by a load-serving entity from an affiliated generation company as strong evidence pointing against any affiliate abuse.”

“Leaving aside the fact that it is a bit rich for Exelon to imply that the Illinois legislature spontaneously decided to award Exelon billions of dollars in subsidies, there is simply no basis for the contention that the commission’s concerns about rates negotiated between affiliates are a function of the level of ‘state involvement,’” EPSA replied. “The commission has a statutory duty to ensure that rates for wholesale sales are just and reasonable and … that duty may not be delegated to the states.”

‘Moral Obligation’

Calpine, which had led a challenge to PJM’s MOPR in 2016, argued that Extended RCO was FERC’s best option, and that it had a duty to it and other generating companies to implement the proposal.

“The commission cannot turn its back on existing generators,” Calpine said. “Not only does the commission have a statutory obligation to ensure that capacity market prices are just and reasonable, the commission also has a moral obligation to implement rules that allow competitive generators the opportunity to recover their investments in the market. …

“Competitive generators have flocked to the PJM market, investing tens of billions of dollars of private money with the understanding that they will have a fair opportunity to recover their investment. There was no guarantee that their investment would be recovered, but there was a regulatory compact that PJM and the commission would protect and defend competitive markets, so investors have the opportunity to compete on a level playing field. … If the commission fails to take the necessary action in this proceeding to shore up the structure of PJM’s capacity market, then the commission must be prepared to develop mechanisms to provide stranded cost recovery for these investors who were otherwise tricked into investing capital in a market with no meaningful opportunity to recover that capital, and a fair return with it.”

Calpine’s claim was rebutted by the Harvard Electricity Law Initiative in the opening lines of its comments. “As the commission considers how to avoid raising wholesale capacity rates, it should discount generators’ warnings that they may demand ‘stranded cost’ recovery if the commission does not approve their preferred approach to the PJM Tariff,” it said.

“Generators’ actual expectations about market rules and prices are premised on a mistaken view of the commission’s ratemaking authority and have no equitable force,” Harvard said. “Generators assert that the commission must approve a ‘clean’ market, untouched by direct and certain indirect government interventions, to ensure that the PJM capacity auction is ‘competitive.’” The judiciary has held that the “just and reasonable” standard in the Federal Power Act does not necessarily mean “structurally competitive,” Harvard noted.

Consumer Responses

A group of industrial customers said the Extended RCO should be rejected because it is essentially identical to the capacity repricing proposal the commission rejected in June as an unjust cost shift. “In addition to discriminating against customers that are captive to states that are subsidizing resources, the Extended RCO is likely to produce pricing outcomes that cannot be defended as being just and reasonable.”

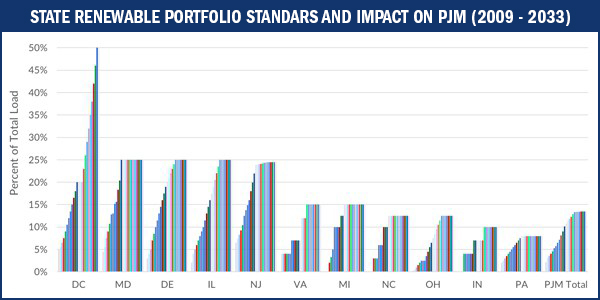

State consumer advocates for Illinois, West Virginia, Delaware, Maryland and D.C. said there is no evidence that state resources are suppressing capacity prices, noting that “PJM has two-thirds more capacity than necessary to meet its reliability requirement, the largest excess of any RTO in North America.”

They also said PJM’s proposed resource-specific criteria for the carve-out are too restrictive. “States should be allowed to count carved-out resources toward resource adequacy requirements according to actual grid needs, which are portfolio-wide and seasonal,” they said.

PJM’s Independent Market Monitor lobbied for its proposed “Sustainable Market Rule,” which would allow all nonmarket resources to participate in the energy market but use the capacity market as a “balancing mechanism” to provide incentives for entry and exit.

“If resources offer at competitive levels and clear the capacity market, the resources are paid the market clearing price. If resources do not clear the capacity market, the resources are not paid for capacity,” the Monitor said. “Any nonmarket revenues required to meet the public policy goals associated with these resources would be provided outside the market in whatever manner the supporters of those resources choose.”

Rich Heidorn Jr. contributed to this report.