By Mark Dyson, Chaz Teplin and Grant Glazer

Last week, RTO Insider published an op-ed from Steve Huntoon that challenged the approach and findings of the latest report from Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) on “clean energy portfolios” (CEPs), defined as combinations of renewables, storage and demand-side management programs that, together, can provide the same energy and reliability services as a gas-fired power plant.

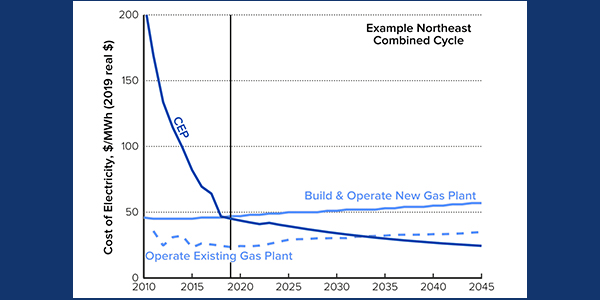

Our study, using detailed modeling approaches and robust, region-specific data, found that 90% of gas plants currently proposed for construction face significant risk of competition from CEPs, and associated stranded-cost risk within 10 to 15 years.

The RMI team welcomes feedback and respectful discourse from all perspectives as it relates to our work and its implications, but Huntoon’s article misses the mark by misrepresenting our motivation, oversimplifying our approach, and downplaying the significance of key findings relevant to investors and other RTO market stakeholders. In dismissing our study as relying on “pixie dust,” Huntoon ignores evidence of the fundamental transition underway in the electricity industry and reflects a view of industry dynamics from a decade or more ago that is unsuited to today’s landscape.

An Evidence-based Study Focused on Financial Viability and Risks

RMI is an independent research and consulting firm focused on market-based, profit-motivated solutions for clean energy. Having observed the plight of the coal industry and its investors in recent years, we set out in our study to answer a simple question: Is gas-fired generation heading down the same pathway that has led coal plants into financial distress and early retirement?

There is evidence that this is already occurring. The Panda Temple project bankruptcy in 2017 was an early warning signal, and the planned closure of a 10–year–old gas plant in California announced in June 2019 suggests a growing trend. Nationally, investors are taking notice, with final investment decisions in new gas capacity declining each year since 2014, and capacity factors for a growing share of new combined cycle gas projects already falling significantly below expectations.

With more than $100 billion in planned gas infrastructure investment through 2025, we set out to examine the risks to shareholders and ratepayers if those investments don’t pan out in today’s rapidly changing competitive environment.

A Transparent Approach with Conservative Assumptions

Huntoon’s first claim about our study is that “numbers are lacking: It’s not possible to validate the data and algorithms.” In fact, we clearly cite every source of data that we rely on, all of which are drawn from industry-standard sources (see pages 27-29 and the technical appendix). We also reference the full mathematical formulation of our model published in our initial, 2018 report (pages 29-37 of the appendix).

Huntoon then challenges our inclusion of energy efficiency and demand response in aggressive quantities. In fact, our estimates are consistent with definitive resource potential assessments from the Electric Power Research Institute, FERC and others, as well as recent evidence from leading utilities. To name just a few examples from the past year: Xcel Energy is including more than 800 MW of EE in its integrated resource plan in Minnesota; Portland General Electric is leaning heavily on demand flexibility in its 2019 IRP while building no new gas; and Glendale Water & Power ran a competitive, all-source procurement that resulted in new EE, DR and other customer-sited resources accounting for approximately 20% of new capacity needs.

Huntoon also argues that it is illogical for us to consider EE and DR only as part of CEPs, and not as complements to gas-fired generation. However, our optimization-based modeling approach shows directly how EE and DR are natural complements to zero-marginal-cost generation from wind and solar, with regionally distinct portfolios that leverage resource diversity and load profile characteristics across seasons and hours. More importantly, in making this argument that a combination of EE, DR and a small gas plant might be less costly than either a big gas plant or a CEP, Huntoon actually bolsters the case that EE and DR are a competitive threat to gas investments if planners do not account for them when sizing projects.

Finally, Huntoon takes issue with the possibility that batteries included in CEPs may be charged with “pixie dust” — or more accurately, energy from fossil-fired generation. To be clear: That is a feature of our analysis, not a bug. This assumption that batteries can be charged from the grid during off-peak hours is consistent with the reality of electricity markets, where off-peak capacity is readily available. Our model also carefully subtracts the energy required for battery storage when calculating the CEP’s net monthly energy generation.

A CEP shouldn’t be restricted from leveraging the current system any more than any other grid asset. Similarly, we would not argue that a new gas plant must keep the lights on without help from other, existing generators. Huntoon’s argument is irrelevant as it pertains to our central finding: that CEPs can compete and win on gas plants’ own turf.

Risks and Uncertainty in an Investment Case for New Gas Capacity

In short, the challenges made by Huntoon against our work are inaccurate, irrelevant or both. Our study finds clear evidence that the majority of proposed gas generation projects are uneconomic to begin with and, if built anyway, will likely lose money well ahead of their expected economic lifetimes. Far from relying on “pixie dust,” our analysis reflects the current state of the market and the inevitable outcomes of further innovation and cost declines in renewables and storage. Perhaps the “pixie dust” that Huntoon refers to is, instead, required to believe forecasts of new gas plant profitability even in light of current market trends and their clear implications.