By Ann McCabe, David A. Svanda and Betty Ann Kane

Given the costs and increasing impacts on resource choices that PJM market rules impose on states, states would benefit from a larger voice at PJM. Compared with its counterparts in other regions, the Organization of PJM States Inc. (OPSI) has less formal engagement and influence on PJM rules and decisions. Strengthening the role of OPSI’s 14 members (13 states and D.C.) would help ensure that states have meaningful opportunities to influence PJM’s rules and policies and could benefit everyone: states, retail and wholesale customers, and PJM.

One example of a PJM rule that impacts state renewable policies and costs to customers is PJM’s proposed change to its capacity market, the expansion of its minimum offer price rule currently under review at FERC. The proposal is estimated to cost customers in the PJM region an additional $5.7 billion per year.

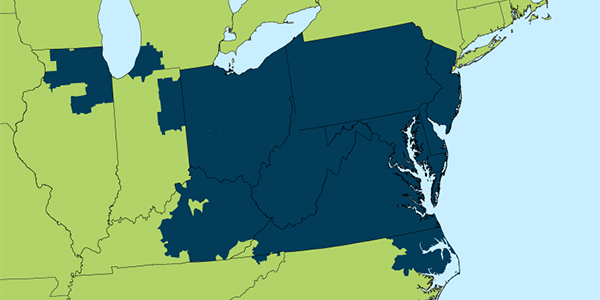

PJM’s footprint | PJM

While the Federal Power Act generally provides PJM states a say over critical energy matters such as resource adequacy planning — how future energy needs will be met — states have seen their influence wane as PJM market rules and policies weight the scales that shape the mix and cost of capacity resources. As a result, PJM’s markets operate increasingly at odds with state energy goals, often at consumer expense.

Like many RTOs, PJM has an official auxiliary group through which states in theory can make their collective voices heard on policies and market rules: OPSI. Consisting largely of state public utility commissioners, OPSI monitors PJM, submits comments and interfaces with the RTO’s board and staff. Unlike state organizations in other RTOs, however, OPSI plays little more than an advisory role. PJM’s current structure leaves states without power to vote on proposed market rules or to file alternatives with FERC.

States’ abilities to directly influence RTO actions vary by region across the U.S. PJM states sit at one end of the spectrum, without voting ability and unable to file challenges with federal regulators. On the other end, states in SPP wield the most authority of any RTO state organization over generation and capacity matters. Taking a look at how RTOs in other parts of the country allow for state engagement is instructive as states in PJM strive for more voice and a better balance between their individual goals and the important role of the regional grid and markets. We overview several RTO/state models in a recent white paper.

Making PJM’s State Committee Work for States

Inspired by the examples of other RTO state committees, here are a few ways to increase the role and influence of PJM states:

- Create stronger communication and collaboration between PJM and states: RTOs in other regions give deference to the views of state committees regardless of their rules. They prioritize a constructive working relationship.

- Provide regular opportunities to provide formal input: OPSI should be able to weigh in on the design of PJM’s capacity market and transmission planning, both of which influence billions of dollars of supply investments and customer impacts.

- Back OPSI’s feedback with bylaws: PJM’s governing documents could have specific opportunities for states’ input and require the RTO to say how it took OPSI’s input into account.

- Give states more power to determine their own capacity needs: By adopting a provision like that available in MISO, individual states would be able to set their own targets for capacity reserves — rather than relying on a single target set by PJM — to better reflect state needs and energy goals.

- Give states the option to supply their own capacity needs: A so-called “fixed resource requirement option” would give states and utilities more flexibility to meet demand on a megawatt-by-megawatt basis.

- Give OPSI the power to make FERC filings: OPSI could be given the power to make its own filings to FERC under FPA Section 205, giving the states more power over resource adequacy planning.

- Give states a role in selecting PJM’s board members: In MISO, for example, the state committee is often represented on the search committee for the RTO’s board members.

- Require PJM to file states’ alternative proposals: PJM could have a provision where it must file an alternative approved by some percentage of OPSI members. In ISO-NE, the percentage is at least 60% of New England Power Pool participants.

These suggestions are not new, but the events of recent years renew their urgency: PJM is proposing significant changes to its market while searching for its next CEO, public utility commissioners have ongoing concerns about consumer costs, and many states are racing toward a renewable energy future.

Changing the balance of power between PJM and its states is critical to prepare the nation’s largest energy grid for the new energy era that lies ahead.