Making the dream of a hydrogen economy reality will require additional technical advances to overcome resource constraints and reduce costs, speakers told the Smart Electric Power Alliance (SEPA) and Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) H2Power conference last week.

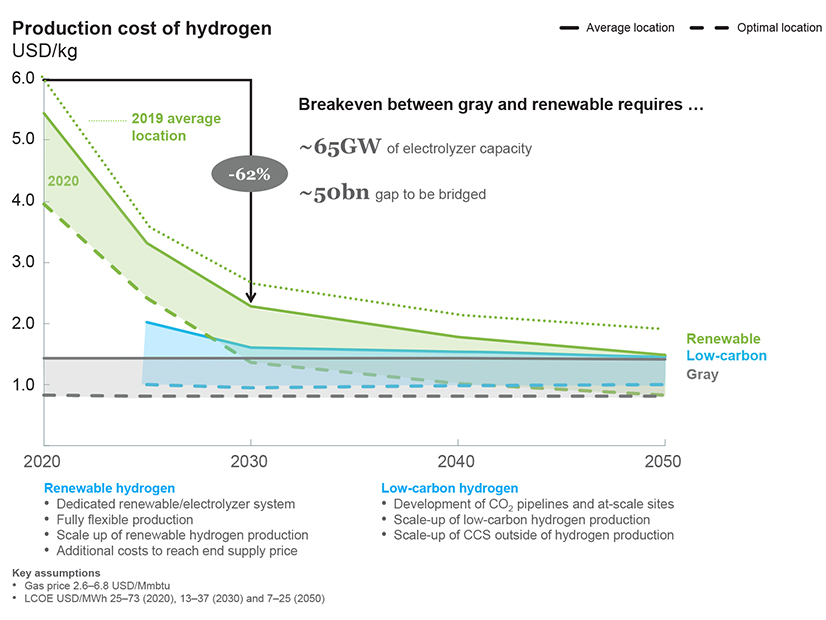

Jigar Shah, director of the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office, said cost reductions won’t come until efforts move beyond research and development to deployment.

“R&D is essential, and we continue to do more of it at the Department of Energy,” he “But you cannot continue to keep doing R&D and expecting the very first deployment to be cheap. And so the first deployments have to happen. And then the second deployment … and every cumulative doubling, gets you this cost reduction curve.”

Xiaoting Wang, an analyst for BloombergNEF, is also impatient for demonstration-scale projects. “Although the technology now still has a lot of space to improve, we think now it is a time to get subsidies from the government … to trigger some demo projects or large-scale [projects], because that will give the first challenge for equipment manufacturers to use automatic manufacturing. Why? Because if the order is very tiny, it does not justify using automatic manufacture, [and it] will not say trigger the first round of cost reduction.”

Getting to Economies of Scale

Katherine Ayers, vice president of research and development for Nel Hydrogen U.S. (OTCMKTS:NLLSY), said achieving economies of scale for electrolysis doesn’t require gigawatt-scale projects.

“Most of these multi-megawatt scale electrolyzers have thousands of cells in them. And so you can get to pretty good numbers from a manufacturing standpoint,” she said.

“I do think that it’s important to … gain experience from some demonstrations to help grease the skids on that. But I think that there’s so many opportunities for electrolysis to serve some of these markets that one of them is going to happen, and it’s going to help the whole space.”

Water, Catalyst Constraints

Some skeptics have questioned the water demands of hydrogen production. Others note that it requires precious metals such as platinum as a catalyst.

Ayers said precious metals “are certainly an area of concern. But we also see many pathways to reduce those [through] manufacturing advancements” to reduce catalyst costs.

The cost of water is less of a concern, she said. “It’s certainly something that has to be considered when you’re implementing a unit because these require high-purity water. But typically, the cost of the water purification — even if you have to desalinate — it is not a huge portion of the cost.

“We have electrolysis units in places like Saudi Arabia, where water is certainly scarce,” she continued. “And if you look at electrolysis, even though it’s using water as the feed source versus some other energy technologies, it’s actually not that high in its usage.”

DOE’s Shah agreed that water use should not be a hindrance to hydrogen’s growth.

“One of the largest users of water in the West is cooling towers for thermal power plants. So they’re already using a lot of water at coal power plants. The total amount of water they’re talking about using here is substantially less than the evaporation losses that are already occurring within the existing coal footprint.”

Transporting Electrons vs. Hydrogen

Another question is how to integrate hydrogen production in the electricity supply chain. Nel Hydrogen’s Ayers acknowledged challenges with transporting and storing hydrogen.

Nel announced last month it had received an order for its containerized 2-MW polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) electrolyzer that will be part of the green hydrogen infrastructure for a fleet of 46 Hyundai trucks in Switzerland.

“Electricity is not that easy to transport either,” she said. “We just had visitors the other day that were looking at our megawatt system and seeing the giant copper cables that have to go to the system in order to power it and the little, tiny hydrogen hose that comes off of it with the megawatt worth of hydrogen. So, you really have to look at how those two things play against each other and not discount the cost of transporting electrons either.”

International Efforts

Cutting the cost of producing hydrogen will not depend solely on U.S. efforts. Ayers said several countries have already committed to gigawatts of hydrogen projects over the next decade.

“There’s huge amounts of activity going on in Europe, largely actually spurred by the pandemic and a desire to use hydrogen as a way to help stimulate the economy as they come out of that. I think that’s really going to help drive these supply chain” improvements, she said.

“Hydrogen from electrolysis is really at a tipping point. And what that means is that competition is also increasing rapidly. So we’re seeing a lot of other companies catching up to what we’re doing here in the U.S., particularly in the PEM area, where I think there’s a lot of technology development happening. One of the things that we’re concerned about is making sure that the U.S. remains competitive in these markets — not just for the electrolysis piece, but also for this … installation experience that’s already going on in places like Europe and China. We’re going to have to learn ourselves as well.”