Participant Funding: ABCs

Participant funding has been a foundational principle in all the RTOs[3] — dating back more than 20 years in PJM for example.[4] Stated simply, a new generator pays for whatever upgrade of the grid is needed to maintain reliability with the interconnection of its project. If the new generator causes a reliability risk, a.k.a. violation, that didn’t exist before, the new generator pays to relieve the violation.

Economics

This principle makes so much sense that even an economist can explain it. Take, for example, a developer pursuing two potential wind projects of the same size and capacity factor; the first would cost about $110 million to build and the second would cost about $90 million. The first would necessitate $10 million in grid upgrades in order to maintain reliability, and the other would cost $50 million in grid upgrades. If the developer has to consider the total cost of its alternative projects, then it will opt for the first project at a total cost of $120 million instead of $140 million for the second. If, instead, others (transmission customers for example) will pay for the upgrades then the developer will opt for the second project at a total cost to it of $90 million instead of $110 million. The generator saves $30 million on its project; transmission customers pay $50 million for the upgrades; and the difference of $20 million is a deadweight loss to society. Not good.

And Fairness

Not only is participant funding economic, it is also fair. Other than paying for any necessary upgrades, the new generator gets access to the grid for free; transmission customers and past generators paid (and pay) for the existing grid. Transmission customers pay for the transmission service from the generator to load. And transmission customers will pay for any upgrades needed in the future even if the new generator contributes to the need for such future upgrades.

The discontents like to say (often in the case of the ANOPR) that a new generator’s upgrades can provide increased transmission capability, a.k.a. “headroom,” that provides system benefits like lower energy costs and higher reliability. What this ignores is that the new generator gets the benefit for free of existing headroom paid for by transmission customers and past generators. To illustrate this, a new generator’s project could increase loading on, say, 10 transmission lines (remembering that this is a grid where new generation injected at a single point is distributed across many lines[5]). On, say, eight of the 10 lines there is existing headroom, paid for by others, such that the project does not cause a reliability violation on those lines. The generator gets to use that headroom for free.[6] On the other two lines there are reliability violations, and the generator pays for upgrades to relieve those violations. Manus manum lavat, hand washes hand.

Speaking of fairness, let’s not forget the many, many billions that investors have contributed to construct and interconnect the existing generation that today provides us reliable electric service at reasonable cost and at declining carbon emissions. Changing the rules now to favor new generation investment, at the disadvantage of past generation investment, would be unfair.

System Benefit Claims

Even if the above weren’t enough — which it ought to be — we need to carefully scrutinize claims of system benefits. Let’s remember at a basic level that whatever energy savings benefit comes from new generators at uneconomic locations, that we’d get roughly the same benefit from new generators at economic locations. Why pay extra to subsidize uneconomic generation?

And a few words about the latest study to claim benefits for customers as a reason to abandon participant funding: A study by the ICF consultancy paid for by the American Council on Renewable Energy (ACORE).[7] In a nutshell ICF started with a pool of 663 network upgrades in SPP and MISO, and selected 12 (2%). One criterion for selection was that the upgrade capital cost be low relative to the potential generation that would be connected; it’s unclear how that might have biased the results. In any event, if you add up all the costs of the 12 upgrades,[8] the total is about $3.3 billion. If you add up all the claimed benefits to load, the total is about $990 million. Somehow these results are supposed to show that we should get rid of participant funding and just bill load for the $3.3 billion. So load would pay $3.3 billion and in return get $990 million of benefits. Such a deal!

The study also ignores the benefits that new generation gets for free from transmission that was paid for by others, as discussed in the preceding section. Is the benefit that new generation gets from others more than the benefit it provides others? I don’t know, and neither does anyone else.

As for the assertion: more transmission = more reliability, this is specious. The grid is planned to satisfy reliability criteria. More transmission facilities driven by the need to interconnect remote generation (the ANOPR’s premise is that the new generation we need is remote) may, or may not, increase reliability. All else equal, the longer the transmission line the less the reliability (think longer lines’ increased exposure to extreme weather and, yes, more squirrels).

Remoteness

The ANOPR tried to come up with a reason why the last 20 years of RTOs developing — and FERC blessing — participant funding should be thrown away. (See FERC Goes Back to the Drawing Board on Tx Planning, Cost Allocation.)

The lead claim seems to be that since Order No. 2003 was issued, “the composition of the generation fleet has rapidly shifted from predominately large, centralized resources to include a large proportion of smaller renewable generators that, due to their distance from load centers, often require extensive interconnection-related network upgrades to interconnect to the transmission system. The significant interconnection-related network upgrades necessary to accommodate geographically remote generation are a result that the commission did not contemplate when it established the interconnection pricing policy for interconnection-related network upgrades.”[9]

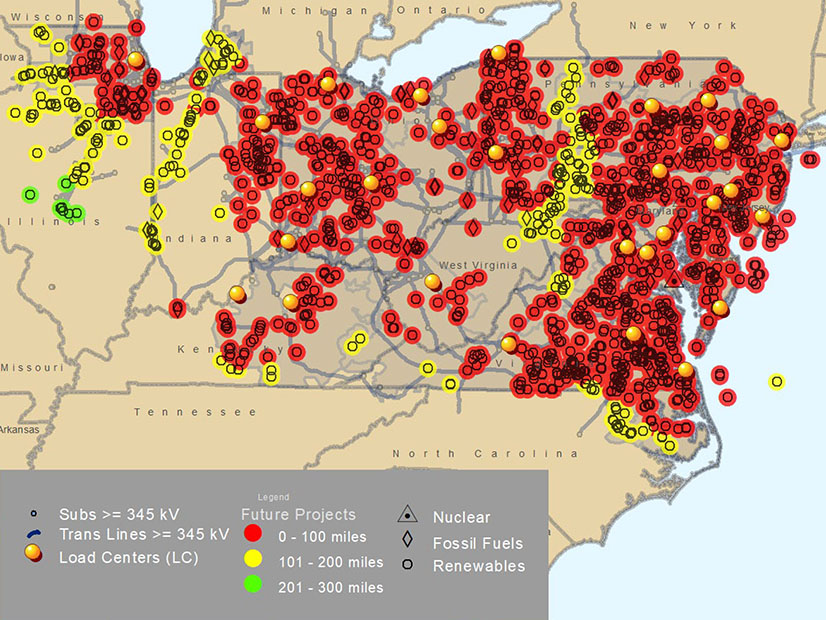

I count four fatal flaws in this thesis. First, I can’t find anything in Order No. 2003 that says participant funding turned on a lack of remote, smaller generation, or that the commission didn’t contemplate the possibility of remote, smaller generation needing “extensive” network upgrades. Second, conditions on the ground when Order No. 2003 was issued don’t support the thesis, as there already were wind projects, such as 30 listed in the PJM queue.[10] Third, currently proposed renewable projects aren’t necessarily remote from load centers as this PJM slide shows.[11] Fourth, perhaps most fundamental, if new renewable generation is relatively remote and if that can cause “extensive” network upgrades, then all the more reason that such generation not be interconnected without considering total cost, including upgrades.

Wrapping Up

Participant funding was the right idea 20 years ago. And it still is.

[1] https://netzeroamerica.princeton.edu/img/Princeton_NZA_Interim_Report_15_Dec_2020_FINAL.pdf, slide 136.

[2] Building for the Future Through Electric Regional Transmission Planning and Cost Allocation and Generator Interconnection, 176 FERC ¶ 61,024, 86 Fed.Reg. 40266 (2021).

[3] The ANOPR states at P 105: “Over time, each RTO/ISO sought, and the Commission accepted, independent entity variations to adopt some form of participant funding rather than the crediting policy.”

[4] PJM Interconnection, L.L.C., 87 FERC ¶ 61,299, at page 17 (1999) (“… generators will be required to pay the full cost of grid expansion …. this type of proposal forces the developer to consider the economic consequences of its siting decisions when evaluating its project options, and should lead to more efficient siting decisions.”).

[5] A good introduction to the basic concepts is here, https://www.e-education.psu.edu/ebf483/node/513.

[6] To get a little technical, take a line that has peak loading of 70 MVA, and a maximum line rating of 100 MVA. Suppose the project increases the peak loading to 85 MVA. Because that is still below the maximum line rating of 100 MVA, the new generator pays nothing for increasing the peak loading.

[7] https://acore.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Just-Reasonable-Transmission-Upgrades-Charged-to-Interconnecting-Generators-Are-Delivering-System-Wide-Benefits.pdf.

[8] Exhibit 2 on page 5.

[9] ANOPR at P 100.

[10] https://pjm.com/planning/services-requests/interconnection-queues, select “Wind” as fuel and the “Dates” tab for queue date.