Parts of New Jersey’s electricity grid are so old and its capacity so limited that new solar projects can’t be connected in certain areas of the state, a weakness that is stifling solar energy expansion, developers told legislators Monday.

During a Senate Energy and Environment Committee hearing for a bill that would levy a fee to generate millions of dollars to modernize the grid, developers said they wait for months, even years, to get projects connected, and sometimes the connection never happens. The problem is worst in South Jersey, where Atlantic City Electric (ACE) (NASDAQ:EXC) is the utility, but parts of the state served by Public Service Electric and Gas (NYSE:PEG) and Jersey Central Power & Light (NYSE:FE)

also have problems, they said.

“We’ve got to modernize the grid,” said Fred DeSanti, executive director of the New Jersey Solar Energy Coalition. “The grid is 100 years old. It was designed for a completely different purpose. We need a system of highways; we need a system of byways. This has got to be equal access, where you can put power in any place and take it out anyplace. The only way to get there is to fund it.

“If we don’t start getting on that road right now, I can tell you that the industry is going to start to really close down,” he said.

The developers spoke in support of S431, which would establish a fixed “grid modernization” fee structure to pay for the cost of upgrading the grid, with the owners or developers of renewable energy systems paying the fee to electric utilities who would carry out the upgrades. The bill would require the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities (BPU) to create different “tiers” for the modernization fees depending on the size of the project, capping the fee for a residential net-metered system of 10 kW or less for the first three years at $50/kW.

The fee would defray the costs of interconnection, including administrative tasks or studies conducted by the utility, and infrastructure upgrades necessary for the safe operation of the renewable energy system, according to the bill. Electric utilities could charge their customers additional fees to recover interconnection costs that are not covered by the modernization fees.

In addition, the legislation would direct the BPU within 18 months of the bill’s enactment to adopt rules and regulations that would create a model procedure that conforms to those of the Interstate Renewable Energy Council (IREC).

The committee solicited public input but did not vote on the bill. A similar bill did not advance in the last legislative period, which ended in January.

Utilities said they recognize, and are taking steps to resolve, the problem.

ACE is “working to create new opportunities for solar in areas where the grid no longer has the available capacity to accommodate more solar installations,” spokesman Francis Tedesco said in an email.

“We continue to invest in and adopt new grid modeling tools and grid automation technologies as they become available,” he said, adding that such technology “allows us to optimize the system and make us better able to accommodate increasing amounts of solar.”

“As a result of our efforts, we have been able to expand interconnection opportunities for solar and continue to notify interested customers of these opportunities as they occur,” he said. “However, even with more sophisticated technologies and tools, physical upgrades to increase the capacity of the local energy grid will be required to accommodate the significant growth of solar we expect to see in the coming years.”

To help meet the challenge, the company is “working with interested stakeholders to identify the most efficient and fair path forward to expand capacity on the local energy grid to create new opportunities for solar,” he said.

PSE&G did not respond to request for comment.

A spokesperson for JCP&L, a subsidiary of FirstEnergy, said the hearing on S431 “provided a valuable opportunity for FirstEnergy representatives to hear the assessments from developers and better understand additional perspectives on interconnection.”

“We look forward to working with the sponsor and other stakeholders to provide future testimony and gather additional comments as this bill continues to evolve,” they said.

Closed Circuits

More than half a dozen solar developers — as well as representatives of the Mid-Atlantic Solar & Storage Industries Association (MSSIA) and the Solar Energy Industries Association — spoke in support of the legislation, outlining a scenario that is urgent and already hurting the industry.

Joshua Lewin, president of Somerville-based Helios Solar Energy, said the company has three customers with projects ranging from 120 kW to 1 MW that have been unable to connect a solar project to the grid. One is a data center; another is a furniture store owner that is trying to convert to clean energy with electric vehicles and heat pumps at his stores and distribution centers; and a third is a union contractor that is looking to convert its vehicle fleet to clean energy.

“Atlantic City Electric has denied us again and again,” he said. “We’ve tried multiple different ways to overcome these issues, and everything unfortunately fell through.”

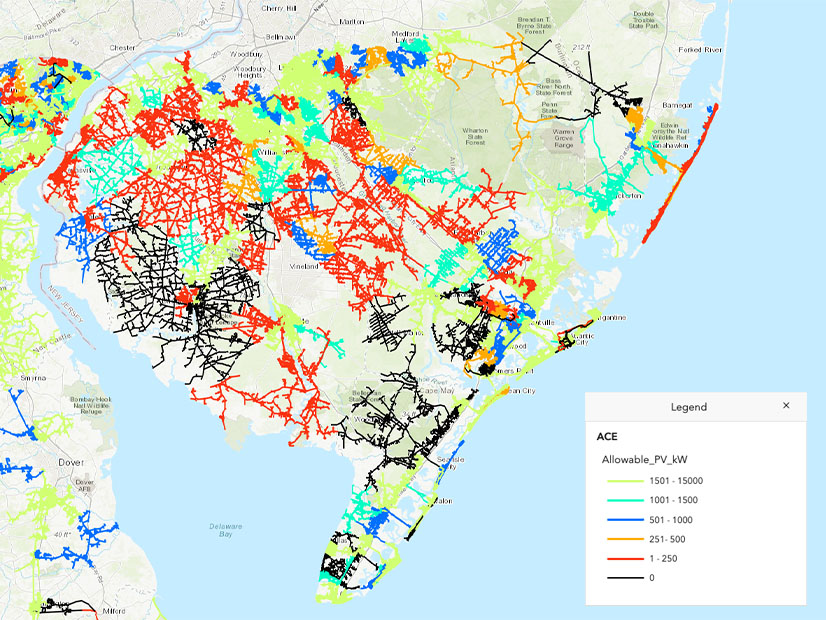

DeSanti said there are now 50 circuits closed to new solar projects in the ACE area and showed the committee a map of the grid in South Jersey, in which some areas were colored black and a larger area was colored red. The grid in the black areas are “completely closed down” to new solar connections, and the area in red can accommodate no more than 250 kW of extra power, or about 25 homes, DeSanti said.

“So that means you can’t host community solar there; you can’t do grid supply there; you can’t host anything but a couple of residential [projects], maybe a small retail or warehouse facility,” he said. “But essentially, that’s pretty close to being closed as well.” He said that the legislation would create a fund to fund to invest in resolving that problem “on the backs of the development community,” who would pay the fee.

In a May 13 letter to the committee, the New Jersey Division of Rate Counsel urged members not to advance the bill, fearing that ratepayers would face unfair charges.

Rate Counsel Director Brian O. Lipman argued that a system to fund grid upgrades through set fees on developers supplemented with contributions from ratepayers would undermine the “beneficiary pays principle.” Under that principle, developers pay for grid upgrades as long as they consider that the risk is worth it and the expense allows the project to be financially viable. By placing the risk of cost overruns on the ratepayers, developers will not be as fiscally responsible in their decisions, the Rate Counsel argued.

Traditionally, the developer will pay if it considers the risk worth the reward, and that without that connection — if the developer just pays a fee and ratepayers cover the remainder — “avoidable and expensive electric system upgrades will be foisted onto captive ratepayers,” the letter said. In addition, by setting the fees every three years, they will lag the actual costs of projects, “possibly for significant periods of time,” and ratepayers may end up paying for upgrades for projects that never get built, the counsel wrote.

Clean Energy Growth

The legislative effort follows a series of hearings launched by the BPU in October that have focused on how to modernize the grid to handle the extra stress of rapidly growing solar and offshore wind generation in the state. The agency expects to release a draft report on the issue on June 27 and a final report later this year. (See NJ Launches Modernization Study.)

The state’s Energy Masterplan describes grid modernization as the “backbone on which all other efforts to transition to a clean energy economy will rely.” The plan sets a goal of 32 GW of solar-generated electricity, 11 GW of offshore wind and 9 GW of storage by 2050.

To reach that goal, the state — which had 3.89 GW of solar capacity in March — will need to deploy 950 MW of solar a year, according to the masterplan. But the state has averaged only 365 MW a year since 2016, according to BPU figures. And that installation rate could decline if developers struggle to get their projects connected to the grid. (See NJ Solar Pipeline Surges While Installations Drop.)

Supporting S431, Doug O’Malley, director of Environment New Jersey, said the grid connection problems potentially could “strangle clean energy projects before they can get onto the grid” and are already doing so.

“The critical thing to remind ourselves is that we have an electric grid that does not work for clean energy projects in a vast amount of the state,” he said. “Right now, we’re seeing essentially a de facto solar moratorium in place for certain parts of the state.”

Spreading Upgrade Costs

Similar concerns were raised by solar developers.

MSSIA President Lyle Rawlings said the grid problems in New Jersey is the “No. 1 issue that we need to address this year.”

“Many members are saying they’re abandoning Atlantic City electric territory altogether,” he said. “We are shutting down this industry, and businesses are leaving the state entirely, because they don’t see a future.”

He said New Jersey needs a statewide solution that would “socialize” the costs, or spread them across all users, replacing the current system, which is unfair, he said. At present, new solar developments connected when the circuit is open can early on be added for little cost but when it can handle no more, “the last one in has to pay for upgrades for the whole circuit, after a large number of projects got a free ride,” Rawlings said.

Kyle Wallace, director of public policy for Sunrun, said that if the modernization fee had been in place in some of the state’s busiest solar installation years — from 2016 to 2018 — it would have raised $3 million a year for grid upgrades. That would have been sufficient to improve the grid enough that those circuits now closed to new projects would still be open, he said.