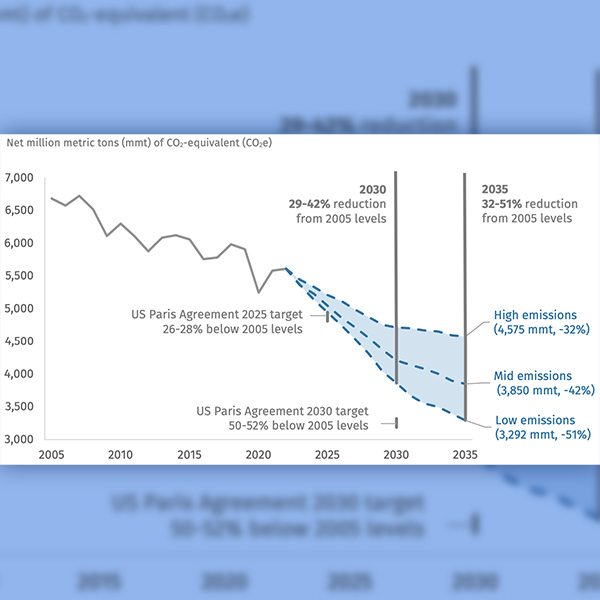

The U.S.’ current policies have it on course to cut emissions by 32 to 51% below 2005 levels by 2035, which is an improvement over previous years but still short of its pledges under the international Paris Agreement, the Rhodium Group said in a report released Thursday.

The country is on track to get to 29 to 42% cuts by 2030, while the Paris Agreement calls for cuts of 50 to 52% by that year.

Rhodium Group releases a version of its “Taking Stock” report every year, and this year it has the benefit of a better understanding of how the Inflation Reduction Act is going to be implemented. The law has Rhodium predicting the power sector will see the largest declines in greenhouse gas emissions in its history of tracking emissions.

“The power sector in particular looks quite different in 2035 compared to today, with zero- and low-emitting power plants making up 63 to 87% of all generation that year, up from around 40% in 2022,” the report said. “Electric vehicles also continue their rapid growth, and, taken together, this progress on decarbonization also reduces household energy bills by an average of $2,200 to $2,400 per year in 2035 from 2022 levels.”

Getting there will be challenging, with the country needing to add 32 to 92 GW per year of wind and solar, while its actual annual record is roughly at the very bottom of that range. That level of deployment “faces headwinds in nearly every direction,” with more work to be done on the supply chain, interconnection, transmission, siting and an expanded workforce.

“Without the IRA, cost competitiveness would be one of the primary barriers to clean energy deployment,” Rhodium said.

While new wind and solar had proven to be cost-competitive with new natural gas before the law, they also have to compete with existing fossil fuel generators, which are either partially or entirely depreciated.

“But if cost is less of a barrier, all the other headwinds remain,” Rhodium said. “Until now, relatively less attention has been paid to these other challenges because cost was front and center. That means policy solutions for overcoming these barriers are less developed and have less political momentum.”

Rhodium estimates “economically rational” deployment of renewables, which means some of those other headwinds are not fully taken into account in the report. The group said it planned to tackle them more completely in future research.

Taking into account announced retirements and future economic decision-making by generators, Rhodium expects the trend of coal plant retirements to accelerate in the coming years, averaging 22 to 23 GW from 2023 to 2025, compared to 12 GW over the past five years. The trend slows down in later years because of a much smaller coal fleet.

“Additions of combined cycle and peaker gas plants also accelerate into the 2030s in the mid- and high-emissions cases,” the paper said. “But gas capacity growth is effectively flat through 2030 in the low emissions case and then starts to decline in the early 2030s.”

The paper’s power sector emissions projections include the impact of federal incentives from the IRA such as the extended clean energy tax credits; tax credits for nuclear, carbon capture and storage; current EPA rules such as the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards; and state policies such as renewable portfolio standards and offshore wind mandates.

EPA’s proposed power plant rule to limit greenhouse gases would require a mix of carbon capture retrofits, hydrogen blending, natural gas co-firing, federally enforceable retirement decisions and capacity factor limitations. The agency has yet to take comments on its proposal, which is likely to change before it is finalized. (See EPA Proposes New Emissions Standards for Power Plants.)

“We generally adopt EPA’s proposed phase-in schedule and the stringency of emissions reductions, but we offer a high degree of flexibility for states to create and submit plans for achieving equivalent levels of emissions reductions,” Rhodium said.