The U.S. must double the number of transmission projects permitted and built each year to meet its clean energy potential, according to the NRDC.

The U.S. must double the number of transmission projects permitted and built each year to meet its clean energy potential, the Natural Resources Defense Council said Wednesday in a report recommending ways to speed permitting rules to allow enough construction to meet midcentury climate goals.

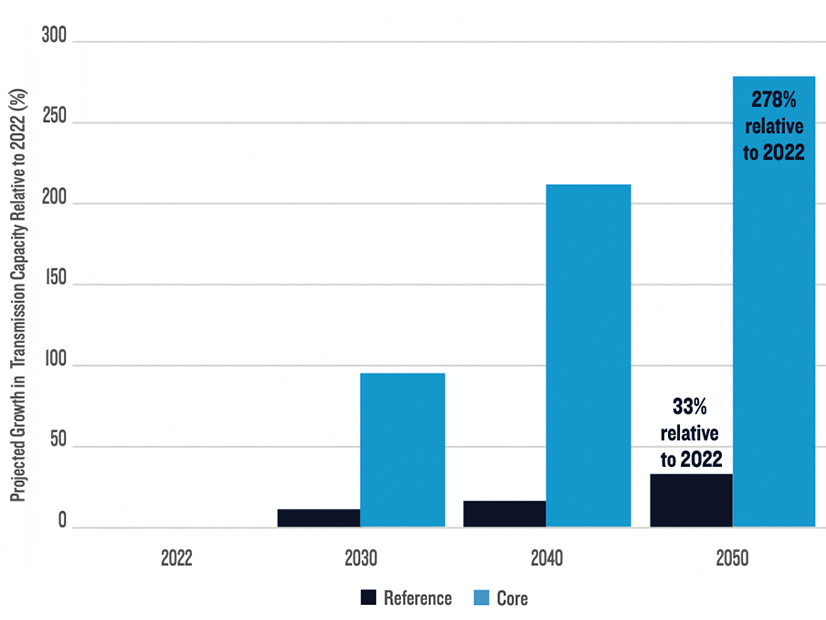

“We also must double the rate at which we expand the transmission system and simultaneously shift to building large interstate transmission lines instead of the small local lines that are mostly added today,” said NRDC Senior Advocate Nathanael Greene, the report’s lead author.

The Inflation Reduction Act is a huge opportunity for the country to roll out renewable energy and make significant progress on cutting greenhouse gas emissions, while the heat and natural disasters this summer show that climate change is happening and must be addressed, Greene said in an interview.

“Those two things I think allowed people to put building things higher on their priority list,” he added.

Issues around permitting have been a major focus for those working on federal energy policy all year, but so far, Congress has passed only a small package that largely ignored transmission. (See Lawmakers, White House Promise More Work on Permitting After Debt Deal.)

It is unclear whether lawmakers will be able to come up with another legislative package, but given the limited time due to the need to fund government operations and election season kicking into gear, NRDC wanted to express views on the subject to help inform any potential legislation, Greene said.

“This is an important conversation for Congress to be having because if a window opens, that’s not going to be open for long, and people need to know what’s important, what to do, what not to do,” he said. “Because it’ll have to happen quickly when it happens.”

A deal could be attached to some kind of must-pass bill this year, which would leave little time for members to examine the legislation, he added.

The report identifies four major barriers to getting needed transmission built, the first being the need to obtain federal authority to site, permit and allocate costs for large interstate lines while increasing community engagement.

FERC and the Department of Energy should work quickly to implement their strengthened authority to designate new “national interest transmission corridors,” the report said. (See States, RTOs Caution DOE on Transmission Corridors.)

NRDC is critical of FERC’s “rubber stamping” of natural gas pipelines, so it wants the agency to do more robust environmental reviews and provide stronger landowner protections when it comes to expanding the electric grid under its limited siting authority. While NRDC has litigated some of FERC’s implementation of the Natural Gas Act, that same kind of “bright line” siting authority would help expand the grid, Greene said.

“As long as it’s a political question about whether they’ll use that authority, it’s always going to be harder for them to do that permitting,” he added.

Ultimately, Congress should pass a law giving DOE authority to plan and FERC the ability to site large, interstate transmission lines, the report said.

Given that many of the projects NRDC wants to see built will cross state lines, having federal agencies planning and siting them makes sense, Greene said.

Another major recommendation is for FERC to “consider all the benefits of transmission” and then allocate them based on who benefits. The commission can implement rules to broadly allocate costs of new transmission to states, but if it fails to do so, then Congress should pass legislation requiring that, the NRDC said.

A pending notice of proposed rulemaking would update FERC’s planning and cost allocation rules. And while Chairman Willie Phillips has called that a priority, it has yet to pass.

Dealing with NIMBY

The report’s second recommendation is meant to deal with the opposition transmission projects often encounter because people do not want major infrastructure built near their homes, but that can be minimized by making community engagement a pre-requisite to siting rather than an afterthought.

“We know all the pieces of doing permitting better,” Greene said. “We just need to integrate and hold people accountable.”

The report suggests ensuring that communities gain benefits from hosting clean energy infrastructure. Specific benefits would vary by project, but they include jobs, environmental protections, financial contributions and energy benefits.

“Some developers already routinely negotiate community benefit packages for their projects,” the report said. “States should incentivize or require this as a best practice.”

The Inflation Reduction Act also earmarked money to help beef up permitting regulators in the states so they can adequately review the expanded pace of transmission development, Greene said.

The report’s third recommendation is to improve federal coordination, accountability and staffing of clean energy permitting and environmental reviews. That can be done without undermining the purpose behind the National Environmental Policy Act, the report said.

“Environmental reviews can be made much more efficient through increased agency resources, greater use of programmatic reviews, and permitting solutions that are tailored specifically to clean energy projects,” the report said.

The final recommendation is to embrace “smart from the start” planning to ensure that clean energy projects deliver conservation benefits and mitigate the impacts. That involves early and robust stakeholder engagement, planning at a landscape level, conservation of lands with important natural resources and cultural values, and moving projects to “low-conflict areas.”

“‘Smart from the start’ is designed to make permitting more efficient and to protect high-value lands by strategically focusing on regional or landscape-level efforts to mitigate the impact of renewable energy resources,” the report said. “These larger mitigation efforts often produce greater conservation outcomes than disparate project-level mitigation.”