The U.S. Supreme Court’s conservative majority on Feb. 21 appeared inclined to pause the Biden administration’s Good Neighbor Plan, an EPA rule to limit ozone-forming nitrogen oxide emissions from power plants and industrial facilities in certain states.

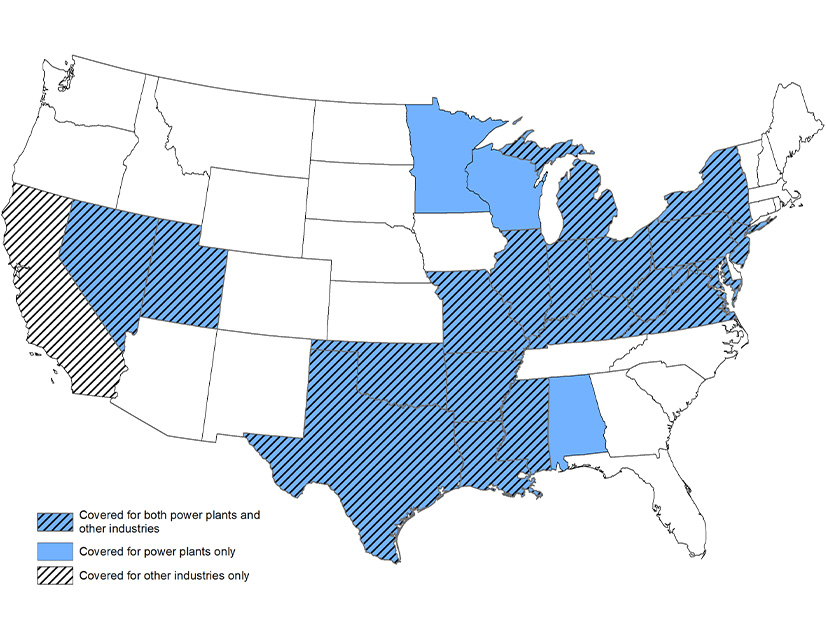

The plan was first proposed in 2022, and EPA issued a final rule early last year that applied to 23 states found to be contributing to unhealthy levels of ground-level ozone in neighboring downwind states, making it difficult for those states to meet the 2015 National Ambient Air Quality Standards.

Lower courts have stayed the rule in 12 states while they consider it, but the agency has continued to enforce it for the remaining 11. The Supreme Court agreed in December to listen to petitions for an emergency stay — consolidating challenges by Ohio, Indiana and West Virginia with those of Kinder Morgan, the American Forest and Paper Association, and U.S. Steel — after the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals declined to rule on the matter while the lower court challenges proceed. Ohio and Indiana are among the remaining 11 states, while West Virginia is not currently required to comply.

Several conservative justices focused on whether the plan’s cost calculations are still justified for the remaining states, while liberal justices expressed concern about the precedent the court would set by ruling before the lower courts had a chance to hear the case.

Representing the states, Ohio Deputy Solicitor General Mathura Sridharan asked the court to pause the implementation of the rule, arguing that “while these [lower court] proceedings are going on, the states and their industries continue to suffer irreparable harm.” An emergency ruling is justified by “the threat of power shortages and heating shortages.”

EPA’s calculation of the compliance cost threshold was set based on all 23 states, and the agency did not adequately consider how removing states from the plan would affect it, said Catherine Stetson, representing the industry challengers.

“What happens if you take out the states where maybe you can control those costs most cheaply and you’re left with states that actually have much higher cost thresholds to impose on industries or on” electric generating units? Stetson asked.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh said the burden is on EPA to show the cost threshold calculated based off all 23 states should still apply to a smaller number of states.

“The problem is we’re not sure if the requirements would be the same with 11 states as with 23,” Kavanaugh said. “It’s just not explained.”

But other justices expressed skepticism that a stay in some states justified a re-evaluation for the others, as the compliance costs are fixed and not changed by the exits.

“If all these lawsuits that the states are bringing are going to end up losing,” said Justice Elena Kagan, “the idea that you can be here and be demanding emergency relief just because states have kicked up a lot of dust seems not the right answer to me.”

Justice Amy Coney Barrett questioned Stetson on the timing of challengers’ request for the Supreme Court to intervene.

“You’ve talked about projected injury, projected costs that you’re going to incur, but, presumably, I mean, the rule’s been in effect for a while,” Barrett said. “Why haven’t you talked about that? I think you’re kind of shifting gears now.”

Stetson responded that EPA’s plan will cause significant costs to power plants over the coming 12 to 18 months, triggering “immediate reliability issues.”

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson said she is concerned about the precedent the Supreme Court would set by pre-empting a ruling from the D.C. Circuit.

“Your argument is just boiling down to, ‘We think we have a meritorious claim, and we don’t want to have to follow the law while we’re challenging it,’” Jackson said. “I don’t understand why every single person who is challenging a rule doesn’t have that same set of circumstances.”

Representing EPA, Deputy U.S. Solicitor General Malcolm Stewart argued that the court must consider harms that pausing the agency’s plan would have on downwind communities.

“To stay the rule in its entirety based on some theoretical possibility that the contours of an 11-state rule might have been somewhat different if EPA had anticipated all the stays would be terribly unfair to the downwind states,” Stewart said.

The agency has said the plan “will save thousands of lives and result in cleaner air and better health for millions of people living in downwind communities.”

The final rule noted that ozone exposure increases risks of early death, exacerbates asthma symptoms and harms ecosystems. EPA also highlighted environmental justice benefits of ozone pollution reductions, noting that the agency’s impact analysis “found greater representation of minority populations in areas with poor air quality relative to the revised ozone standard than in the U.S. as a whole.”

“The harms from a stay will flow to both the residents of downwind states who will experience health dangers and to downwind industry, which pays increased costs to compensate for upwind pollution and comply with the current, more stringent standard,” New York Deputy Solicitor General Judith Vale said, representing states in support of the rule.

Vale argued that the costs of pausing the rule would be greater to downwind states than the costs the rule would impose on upwind states, noting that the rule requires “controls that downwind sources and many other sources across the country have already done, … like turning on pollution controls on power plants that are already installed.”

Kavanaugh said both sides have shown evidence for harm, and therefore the “only other factor on which we can decide this under our traditional standard is likelihood of success on the merits.”

When considering the merits, Kavanaugh said the court must evaluate whether EPA’s methodology was arbitrary and capricious.

“One of the classic arbitrary and capricious conclusions is a failure to explain,” Kavanaugh said. “One of the complaints they have, which we have to evaluate, is whether they’re likely to succeed in saying that the rule was not adequately explained.”