Lengthy wait times in PJM’s generator interconnection queue are interacting with siting and permitting timelines, supply chain disruptions and inflation to contribute to increasingly long construction periods, according to a study released last week by Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

The report, “Outlook for Pending Generation in the PJM Interconnection Queue,” surveyed 30 developers with projects in the “advanced stage” of the queue regarding the amount of time it would take for them to reach commercial operations after receiving an interconnection service agreement (ISA) and what major roadblocks could stymie those projects.

“The key finding from the survey is that PJM’s increasingly lengthy interconnection process is exacerbating siting and permitting challenges and leading to knock-on delays in equipment procurement and financing decisions, suggesting the timeline for new generation in this market will likely remain long for the foreseeable future,” wrote the authors, Abraham Silverman and Zachary A. Wendling. “Given the importance of new entry to keeping prices competitive and maintaining reliability amid the retirement of older fossil resources, PJM will need to find ways to reduce interconnection delays or reconsider when those fossil resources should be retired.”

The amount of time for a project to go from design to completion has been increasing over the past five years, the study said, and in PJM, the time it takes for a new interconnection service request to receive an ISA has increased from two years to five.

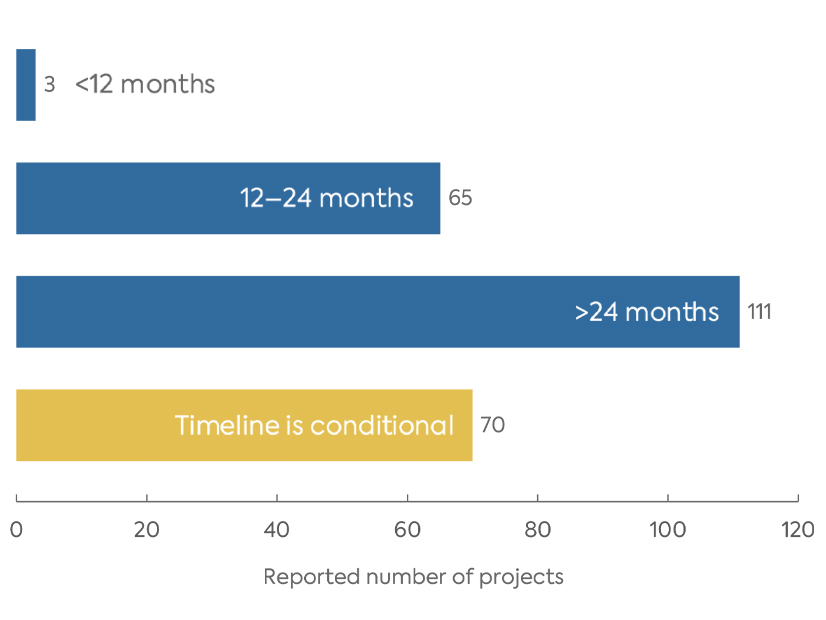

If they were to receive an ISA today, participating developers said about 1% of the 249 projects they collectively have in PJM’s queue would be able to reach commercial operation within a year, while 26% could be completed within two years and 45% would take even longer. Among the 28% of projects with an in-service date conditioned on factors that made completion difficult to predict, siting and permitting was the largest source of uncertainty, along with supply chain constraints and the cost of transmission upgrades.

Because local siting approvals and permits tend to be valid for up to two years, developers said uncertainty around their timelines for receiving an ISA has led many to wait until their interconnection studies have been complete to seek new permits, which can add time to how long it takes projects to get off the ground after PJM has completed its studies.

One developer interviewed as part of the study described the interaction between the queue and permitting as “a bit of a chicken-and-an-egg problem: Ideally you would time these things so [permitting and construction] would come together, but until you have some kind of certainty that you are going to get an interconnection, we’ve been unwilling to make massive spending on permitting.”

State regulations and siting requirements can complicate the matter as well, with West Virginia and New Jersey called out by developers for having rules that prove difficult for solar developers to navigate, and local authorities opposed to projects subjecting them to “a never-ending appeals process.”

Offshore wind developers said federal regulators desire flexibility around projects’ points of interconnection or turbine designs, changes that can trigger PJM to restart the interconnection process.

The study also questioned a central premise of the cluster-based interconnection process PJM embarked on this year: that many developers were submitting multiple interconnection requests for the same project to determine which point of interconnection would result in the least expensive network upgrade allocation. Part of the justification for including increasingly large readiness deposits as proposals progress through the queue was to weed out speculative projects. (See FERC Approves PJM Plan to Speed Interconnection Queue.)

“The extent to which these duplicative requests slow down PJM’s efforts to complete interconnection studies has been hotly debated, and several of PJM’s recent queue reforms were designed to eliminate them,” the study said. “In the sample, only one developer identified an interconnection queue request that had been suspended or paused because it was extremely similar to another project with a separate queue position. Given this issue has been a major theme in PJM discourse, it was surprising to find only a single instance of it among … all the projects in the survey, though it is possible that developers are unwilling to self-report filing a duplicative or speculative interconnection request.”

PJM spokesperson Jeff Shields disputed the report’s finding that speculative projects did not contribute to the queue backlog, saying there were 734 projects eligible for study when the RTO began implementing the new study approach last year, 118 of which dropped out or did not meet the new readiness requirements.

He said most of the issues the report laid out are being addressed by the revised process, which has been on pace since implementation began last summer and is expected to clear about 72 GW of generation by mid-2025 and 230 GW over the next three years. The approach is designed to streamline the process for developers and provide more “transparency, certainty and equity,” Shields said in an email.

“The delays for new projects are related to the fact that there are such a high number of megawatts in the queue ahead of them. What’s more concerning is the 450-plus projects totaling nearly 40,000 MW that have cleared PJM’s study process without moving to construction and operation due to siting, financing and/or supply chain challenges not related to PJM’s process,” he wrote.

Shields said network upgrade costs should pose minimal barrier for the 26 GW of projects sorted into the expedited process, which places proposals in a fast lane if they’re allocated less than $5 million in upgrades.