Puerto Rican company Pluvia filed a petition with FERC in February asking the commission to find that its proposal to link the territory to the continental U.S. via grid-scale batteries on cargo ships could trigger its jurisdiction over the island (EL25-57).

The batteries being shipped back and forth would be storage-as-transmission-only assets (SATOA), and similar projects have been proposed using railcars. The mobile storage also could ship power the other way. The firm’s filing says the technology could be used for day-to-day shipping and under emergency conditions.

The firm filed its petition in early February, and FERC noticed it a couple of weeks later. It largely has flown under the radar, with only Public Citizen filing a “doc-less” motion to intervene before the comment period closed March 3.

Pluvia describes itself only as “a domestic limited liability company wholly owned by citizens of the United States and organized under the laws of the commonwealth of Puerto Rico, inter alia, to produce, transmit and sell electric energy at wholesale.” Exactly who is behind the firm is unclear: Its petition was filed by one lawyer, and its incorporation documents with Puerto Rican authorities only list another lawyer.

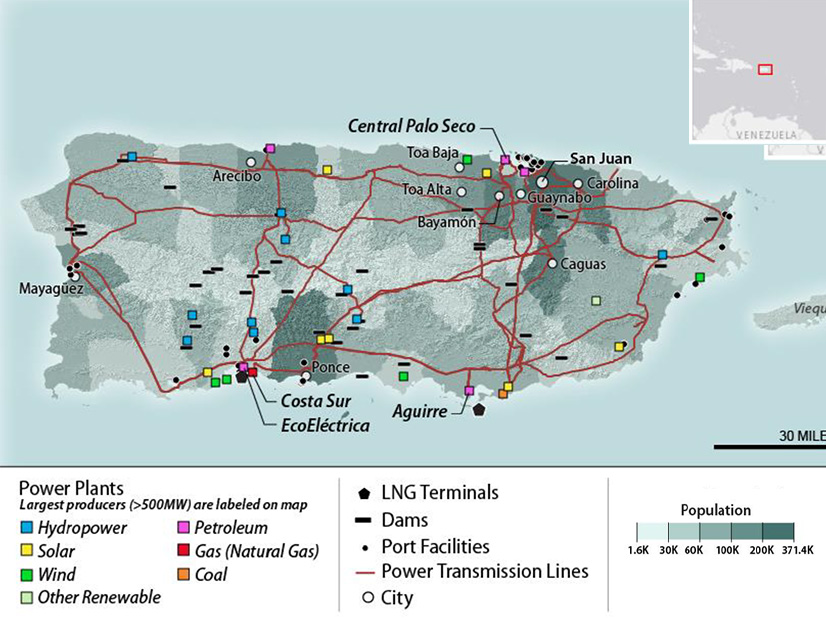

The state-owned Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) entered into contracts with Luma Energy (a subsidiary of Canadian utility Atco and Quantas Services) to run its grid in 2021, and with Genera PR (a subsidiary of the LNG firm New Fortress Energy) to run its generation in 2023. Pluvia told FERC that those deals have kept a monopoly in place, which is overall detrimental to the island’s population.

“Public electricity monopolies have been effectively managed by other states, which have cooperated to lower costs and improve service to customers by implementing federal electric competition policy under the” Federal Power Act, Pluvia said. “The government of Puerto Rico’s administration, however, has been unsuccessful. The damage Puerto Rico’s electricity monopoly has caused is considered a human-made disaster with appalling humanitarian and economic impacts in Puerto Rico that also impact United States taxpayers.”

The island infamously was impacted by Hurricane Maria, which in 2017 destroyed the island’s power grid and kept some of its residents without power for four weeks.

“It’s really not done well since the hurricanes; the reliability of the system is probably about 10 times worse in terms of safety and safety metrics than the U.S. average,” Cathy Kunkel, energy consultant for the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, said in an interview. “And the reliability has actually declined over the last year or so.”

PREPA’s system was contracted to Luma and Genera after the hurricane, with Kunkel saying it was not sold outright because that would have put at risk federal disaster relief funds being used to shore up the grid.

High costs and an unreliable power system have been impairments to economic growth on the island and its ability to stop people from moving to the mainland, Pluvia said in its petition.

On top of still running a creaky grid before and after Maria ravaged PREPA’s system, the public utility has been bankrupt, which has hampered its ability to attract needed investment, Pluvia said

“PREPA’s lack of credit creates a barrier to normal project financing for energy projects, as financing sources hesitate to bet on PREPA’s performance of its long-term contractual obligations to buy electricity in quantities and at prices stated in” power purchase agreements, Pluvia said.

The combination of public monopoly and insolvency leads consumers and investors to a dead end, while creating the misleading appearance of an energy transition through multiple phases of bids and awards that produce contracts needing affordable financing, it added.

While Pluvia and its backers might have run into trouble with securing contacts, Kunkel noted that major deals have been struck recently.

“There’s definitely been long-term contracts that have been signed in the last several years,” Kunkel said. “There’s been a number of new renewable energy contracts and some battery storage contracts and a new natural gas plant contract that was signed in December.”

Another trend since Maria has been end-use consumers’ increasing adoption of distributed solar and storage, which Kunkel said makes up about 9% of Puerto Rico’s electricity consumption.

The issue of FERC jurisdiction over Puerto Rico’s grid has come up before, such as when Alternative Transmission filed a petition in 2023 seeking a finding from the commission that its proposed undersea cable would not trigger commission jurisdiction (EL23-14). The project and its details were a little too vague for FERC to give a firm answer, but it did discuss the jurisdictional issues and said it could forswear oversight of Puerto Rico’s grid as it has in similar cases involving ERCOT. (See FERC Weighs in on Jurisdictional Questions over Puerto Rico Project.)

The Alternative Transmission case came up in Pluvia’s petition as it seeks to clarify that its proposal of shipping batteries back and forth by sea could trigger FERC jurisdiction over the island’s power system, which the commission said could happen with an undersea cable.

The petition does not ask FERC to claim jurisdiction immediately, but Pluvia said it may request that in future proceedings, and it expressly reserved the right to do so.

Puerto Rico has a version of a state regulator already called the Energy Bureau, which was set up about a decade ago to oversee PREPA. IEEFA’s Kunkel said it has helped bring some normality to the island’s regulatory structure.

“One of the problems with PREPA … was that it really had just kind of become a very politically driven entity and was not making decisions based on best-practice, sound utility planning,” Kunkel said. “For example, it had not had a base rate case since the 1980s. One of the first things that the Energy [Bureau] did was to have a base rate case.”

As for bringing RTO-style markets to the island, it is unclear how much benefit they would bring: Puerto Rico’s system is far smaller than any of the continental organized markets, meaning it would lack the benefits that come from centrally dispatching large amounts of generation across a wide footprint, Kunkel said.