Summer’s officially over, white shoes have been relegated to the back of the closet, and pumpkin spice everything is back. Now that the worst of the hot weather is most likely behind us for the year, it’s a good time to reflect on the pressure that extreme heat puts on the electric system.

Extreme weather has earned its way onto the short list of life’s certainties. Whether it’s heat waves, excessive precipitation, storms or freezes, there’s a higher chance than ever that where you live or where your company does business will be affected by extreme weather in ways that are as varied as the biblical plagues.

Heat affects the full length of the electric supply chain, from generation, through the grid, to utilities’ customers. In the first of a series on the impacts of climate extremes, this column will dig into the many ways hotter weather challenges the electric system.

Hot Town, Summer in the City

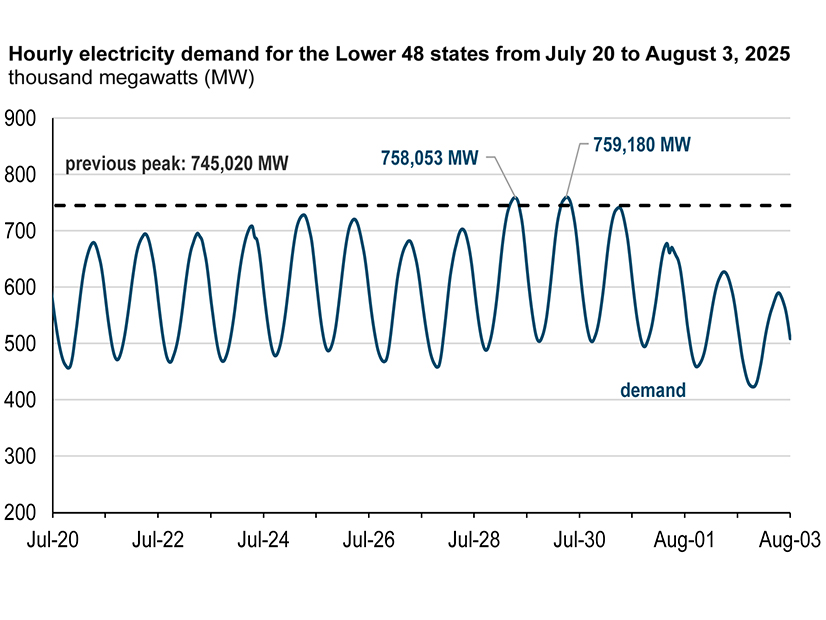

Extreme heat drives demand spikes. On July 28, 2025, peak demand in the lower 48 states broke the record set in July 2024, only to surpass it the next day. The peak demand of 759,180 MW between 6 and 7 p.m. July 29, adjusted for time zones, was nearly 2% higher than the July 2024 record.

The demand is driven largely by an increase in the cooling load, though there probably were some AI servers churning out answers to heat-related questions: How can I cool my home? Will a blended margarita cool me down more than one on the rocks?

It’s not a surprise that demand spikes with heat: Who doesn’t want to walk into a cool home at the end of a hot commute? But heat waves are changing what these demand spikes look like. It’s not just that it takes more energy to cool a home when outdoor temperatures are higher than usual, but also that those with air conditioning are using it longer.

Heat waves can show no mercy at night. Earlier in 2025, some areas in the Southwest saw overnight lows as high as 95°F. This means household cooling loads extended well beyond the typical peak hours from 4 p.m. to 8 or 9 p.m.

Cooling a home becomes more challenging as the heat wave lingers. A home’s thermal mass—dense building materials such as brick, concrete or stone — absorbs heat and radiates it out during cooler periods. Usually, the thermal mass protects a home from heat (that’s why it’s cool inside a building with thick stone walls), but exposure to multiple days of extreme temperatures can slow down how a home cools at night and result in heat continuing to radiate after the heat wave ends.

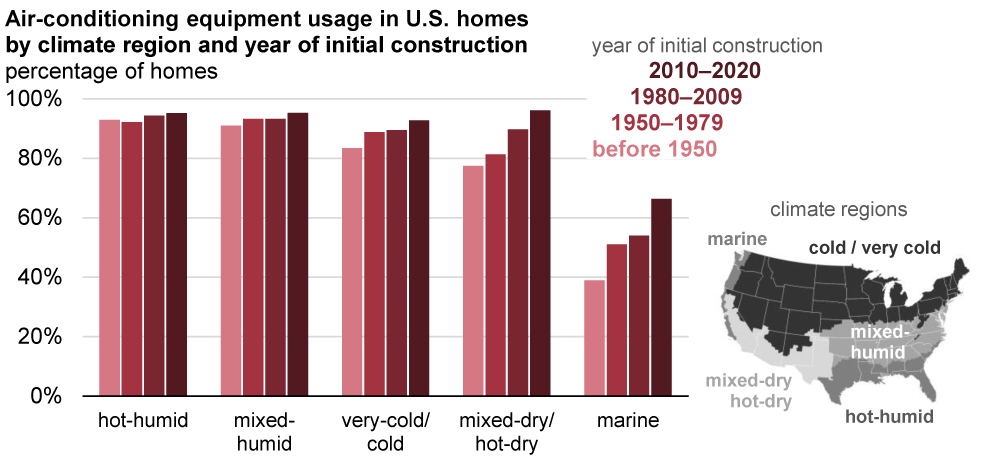

Growing home sizes and increasing adoption of home cooling systems also increase demand. The results can be a capacity deficiency as demand spikes in areas not known for extreme heat, such as the spike ISO-NE dealt with in June.

The biggest change is happening in what the Building America program calls the marine climate region, which extends from the San Francisco Bay Area along the coast all the way to Canada. After record-breaking heat waves in the Pacific Northwest — in June 2021, Portland hit a record 116°F while Seattle hit 108°F, and then in late August 2025, Portland again recorded temperatures over 100°F — installing air conditioning in new homes is becoming common.

The bottom line: The grid will need to plan for ever-higher and longer demand spikes if it wants to maintain reliability.

Heat Strains Supply on Many Fronts

If the only challenge were meeting those demand spikes, the electric system probably would be in good shape. But generation and the grid itself are less efficient during extreme heat, sometimes dramatically so.

The first challenge comes from hot air being less dense: Combined cycle and gas combustion plants are less efficient when the air mixed with the gas to combust in the turbines is less dense.

Efficiency losses vary based on technology, but almost all are affected by heat, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists: “Many types of power plants become less efficient at higher temperatures. A gas turbine rated at 60° F might be able to generate only 85% of that capacity when ambient temperatures reach 100° F, for example.”

Similarly, power plants that use dry cooling, which works like a giant car radiator, have difficulty when the air needed for cooling already is heated.

The bigger challenge comes from hot water: All generation plants that involve combustion require cooling, regardless of whether they burn fossil fuels or split atoms. Most use water for cooling, which means drawing from seas and the like. If that water is hotter than usual before the cooling process, it will be less efficient at cooling, and there usually are limits on discharging hot water.

For example, nuclear reactors in Switzerland and France were throttled after heat waves warmed the water coming in so much that it couldn’t effectively cool the plants and environmental restrictions prevented them from discharging hot water into already overly warm rivers.

While most of these losses can be anticipated, extreme heat can cause extreme outcomes.

Attack of the Overheated Jellyfish

Not once, but twice this summer, the European grid had to cope with unplanned supply shocks because of [checks notes] jellyfish…?

It’s a story that sounds straight out of the eco-thriller “The Swarm”: The warming planet leads to a hotter English Channel, causing jellyfish to thrive, resulting in a “massive and unpredictable” horde of them in a French nuclear plant’s seawater cooling system. It happened in August, and closed four of six reactors, cutting output by 3.6 GW. Less than a month later, and only 165 miles up the road, another jellyfish swarm led to the shutdown of one reactor and the throttling of another, taking 2.4 GW offline.

While jellyfish swarms may be unpredictable, what we can predict is that heat waves will have widespread and varied consequences.

Renewables also are Challenged by Heat

Certain types of heat can make wind farms less efficient too. Heat lowers air density, and wind turbines produce less power when the air’s easier for the blades to pass through, so any hot day will cut production. However, when a stagnant high-pressure weather pattern settles in and creates a heat dome, the problems multiply: Low winds and less variation in wind speeds at different heights from the ground both cut output. A research paper in Europe found the impact varies by location, but one heat wave cut wind power output by more than 30%.

Hydroelectric output’s not immune either. Early heat waves in 2023 melted snowpack in the Pacific Northwest, leaving less water flow for the summer. Overall, the May heat wave decreased output 23% in Washington state across the 2022/23 water year. (Like the school year, the water year is not aligned with the calendar: It starts on Oct. 1.) Of course, heat often is associated with drought, which also limits hydroelectric output.

What about solar? More sun is good, right? Not if it comes with heat. There’s a reason Chile’s Atacama Desert is a prime location for utility-scale solar: It’s cool and sunny. Electronics are more efficient as temperatures drop, and every degree of extra heat lowers the output of a solar module.

Solar module datasheets include a measure called Pmax: the peak power the module can produce at standard operating conditions of 25°C (77°F). Right after that number, there’s always a temperature coefficient: the percentage drop in efficiency for every degree Celsius above 25°C.

While newer solar modules are less temperature sensitive, most still lose around 0.35 to 0.40% efficiency for each degree. This means that back in May, when Texas hit an early heat wave, exceeding 100°F (38C) in Austin — more than 7°C above the average high of 87°F (30.5°C) — the solar farms were delivering at least 2.6% less peak power than they would have on a normal summer day.

That sounds like a small amount of loss, but it was significant, as ERCOT recorded peak usage of over 78 GW, setting a record in May and again pushing the grid to its limits in July. And who wants their utility asking them to limit the use of air conditioning when the nights get down only to the 80s?

Even the Grid Wilts in the Heat

Like all of us, the grid is saggy and inefficient during heat waves. The power lines not only stretch, but also are less efficient conductors as the heat vibrates the conductive material and slows the flow of electrons. So, line losses, which typically consume 5% of electricity across the grid, increase during heat waves, meaning more generation is required to deliver the same amount of electricity where it’s needed.

PNNL researchers have discovered that adding graphene to copper conductors reduces heat-related disruptions. However, with 5.5 million of miles of transmission and distribution lines already deployed, it’s unlikely that efficiency will improve anytime soon.

Labor Sizzles as Temperatures Soar

As heat waves get longer and hotter, generation asset construction and grid upgrades and maintenance also are at risk. Heat accounts for about $100 billion in lost productivity nationally, and any industry where labor works outside is affected.

Some states are instituting worker protections that require breaks, shade and other cooling for outdoor workers (as someone who’s at high risk of heat stroke, I have to give a shout-out to Heat Relief Depot’s phase-changing vests). Some of those regulations have followed heat-related deaths. Other states, such as Florida, are doing the opposite: banning worker protections. But with or without protection, it’s reasonable to assume outdoor worker productivity will decline during excessive heat.

Upstream is not Immune

While we’ve looked from generation to end user, extreme heat has effects all the way upstream in the fossil industry.

In the ultimate irony, melting permafrost puts pipeline foundations at risk of sinking and causing a rupture in the pipeline. It’s a problem in Alaska and other arctic regions, and often is managed using passive thermosyphons (think of vertical radiators around pilings). However, hotter ambient air renders them less effective, and refreezing the permafrost under pipeline footings may require running fossil fuel-powered chillers.

A Hot Take on the Markets

The industry already knows how to manage hot weather. However, to think of extreme heat events as just extra hot weather is a mistake. Excessive and persistent heat, with little nighttime relief, creates challenges that are more diverse and harder to model. So, how should the electricity markets plan for extreme heat?

First, it means that the RTOs are on the right path as they aim to raise installed reserve margins and encourage demand response programs. And utilities should incentivize anything that can temper those peaks, from distributed energy storage to more efficient cooling technologies, such as rebates for mini-splits.

Second, as extreme heat events become more common, the industry needs to plan for them in a nuanced way. It’s critical to understand the wide and varied impact on generation assets. Gas and nuclear? Keep an eye on how they keep cool. Wind? Beware of the heat domes. And given that solar’s decline in efficiency in extreme heat events is easy to calculate (and has zero jellyfish-related risk), it may be time for RTOs to reconsider how they think of solar’s reliability. It’s not just about generation assets: The industry’s ultimate asset is its people, so thinking about worker safety also is critical.

Finally, extreme heat risk reinforces the need to diversify generation and consider where energy storage assets can best act as a shock absorber for the grid. They are, of course, useful sited next to intermittent generation assets, but there’s a strong argument to think of all generation assets as intermittent when extreme heat events are concerned.

Power Play Columnist Dej Knuckey is a climate and energy writer with decades of industry experience.