The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory released a paper recently examining why some states have seen retail power prices rise faster than inflation. The listed reasons include distribution investments, extreme weather and wildfire, natural gas prices and state renewable targets.

“Factors influencing recent trends in retail electricity prices in the United States” includes an article in The Electricity Journal. It found that states in the Northeast and on the West Coast saw some of the biggest price increases from 2019 to 2024 but noted the national averages were in line with inflation.

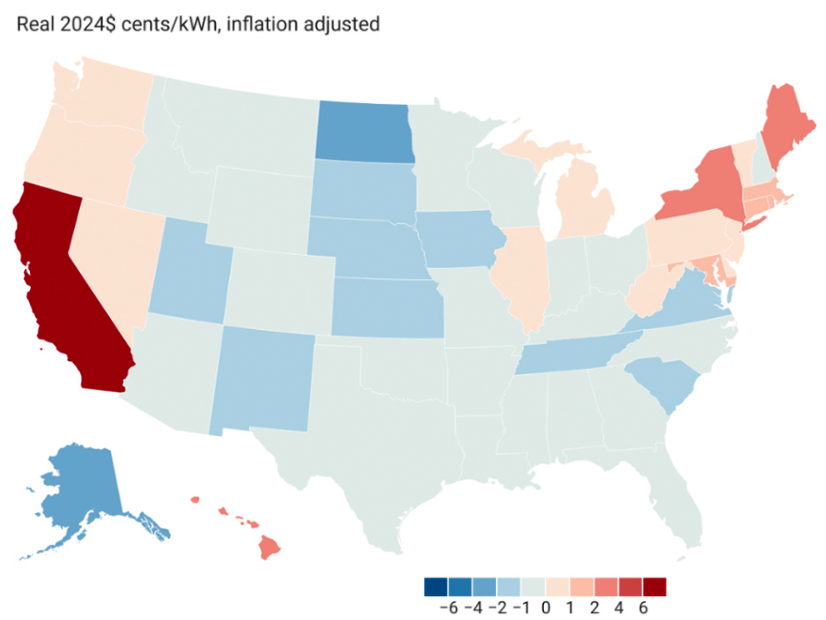

In nominal terms, prices rose 23% between 2019 and 2024. Controlling for inflation, they were flat outside of a bump in 2022 related to the Ukraine-Russia war’s effect on natural gas prices. The national average masks a big difference in state average prices that range from 8 cents/kWh in North Dakota to more than 27 cents/kWh in California.

“Examining recent trends in inflation-adjusted prices, 31 states saw real price declines from 2019 to 2024, while 17 states experienced increases,” the article said. “States on the West Coast and in the Northeast were most affected by rising prices — especially California, where average retail prices increased by 6.2 cents/kWh in real 2024 dollars.”

States with the greatest price decreases typically exhibited increasing customer loads over that period, which misses the recent run-up in PJM capacity prices in the 2025/2026 auctions that are affecting customer bills now, according to a presentation accompanying the study.

PJM’s Independent Market Monitor found that new data center load contributed to the largest chunk of the capacity price increase (alongside some market design parameters), and most PJM states saw retail prices jump from 10 to 15% when the new delivery year started.

Rising demand from data centers, manufacturing and other sources has been cited as creating a risk of higher prices due to their purported impact on wholesale markets, higher retail prices or cost allocation policies that might favor large commercial and industrial customers in the name of economic development. But the study found that load growth from 2019 to 2024 tended to reduce retail prices.

“In the 2019-2024 time frame, the regression suggests that a 10% increase in load was associated with a 0.6 (±0.1) cent/kWh reduction in prices, on average,” the article said.

That aligns with the understanding that a primary driver for utility spending has been refurbishing existing transmission and distribution infrastructure in recent years. Spreading those costs over a larger base cuts average prices, but the study noted that negative load-price relationship was seen in average prices and lost when focused on residential prices.

“Load growth over this historical period was led by commercial customers, and cost allocation practices have tended to benefit those large, non-residential customers,” the article said.

The study focuses on average prices across customer classes, but it noted that residential prices generally are higher than commercial and industrial prices and have risen more than those classes in recent years.

Investor-owned utilities have seen prices rise faster than public power, but the article noted that in California it is largely due to differences in wildfire risk and related costs.

“States with the greatest price increases typically exhibited shrinking customer loads — partially linked to growth in net metered behind-the-meter solar — and had renewables portfolio standards (RPS) in concert with relatively costly incremental renewable energy supplies,” the article said.

Net energy metering offers participants bill savings, but utilities must invest more in their distribution systems and recover fewer fixed costs from customers on NEM programs. The study found a 5% increase in net-metered, behind-the-meter solar led to an average price increase of 1.1 cents/kWh.

Utility-scale wind and solar development that happened outside of RPS might have led to lower retail prices in recent years, though the impact was not statistically significant, the article said. It added that RPS targets are likely to increase prices if they lead to renewables the market would not have delivered. Three-quarters of utility-scale wind and solar growth from 2019 to 2024 happened outside of RPS mandates.

Another major driver of higher prices is extreme weather, which impacts two of the states that have seen prices rise the most in recent years – Maine and California. Central Maine Power’s storm recovery cost rider rose from 0.1 cents/kWh in late 2020 to 1.8 cents/kWh in 2024.

“Between 2019 and 2023, California’s three large IOUs were authorized to include $27 billion in wildfire-related costs in retail prices,” the article said. “By June 2024, wildfire-related costs constituted an average of 17 % of total IOU revenue requirements, up from 1.7 % in 2019 and, if directly translated into one-year cost impacts, equivalent to a 4 cent/kWh increase.”

On average, the states with the highest wildfire risks have seen power prices rise by 1.1 cents/kWh, the article said.