All seven clean energy technologies evaluated for a new report might someday help New York reach its decarbonization goals, but each would require innovation and support to reach that potential.

All seven clean energy technologies evaluated for a new report might someday help New York reach its decarbonization goals, but each would require innovation and support to reach that potential.

The authors say that while hydrogen, biofuels, advanced nuclear, carbon capture and storage, next-generation geothermal, long-duration energy storage and virtual power plants all are in development, none exists at a scale to serve as a dispatchable emissions-free resource to backstop all the intermittent wind and solar generation New York wants to build.

The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority submitted the “Zero by 40 Technoeconomic Assessment” to the Department of Public Service on Oct. 22 (15-E-0302).

The report was prepared by the Electric Power Research Institute. Its title alludes to the state’s statutory goal of a zero-emission power grid by 2040.

The Public Service Commission in May 2023 ordered the report to identify methods of closing the gap between existing renewable energy technologies and future system reliability needs.

The cost and complexity of all-new or greatly expanded infrastructure is likely to be a limiting factor in the near term, giving a larger role by default to technologies that would not require significant infrastructure upgrades, the authors wrote.

The report comes as the state’s clean-energy transition lags well behind the timeline envisioned for it. State officials expect to miss the 2030 statutory goal of 70% renewable energy, perhaps by a wide margin. Delayed fossil retirements or even new fossil generation are being contemplated as a result.

The report groups the seven technologies evaluated into three functional categories: low capacity factor resources to deploy at peak system need (hydrogen and biofuels); high capacity factor resources that can a provide firm supplement to renewables (advanced nuclear, next-generation geothermal and CCS attached to thermal plants); and filling gaps with resources to balance supply and demand (long-duration storage and VPPs).

Hydrogen

Hydrogen can be a zero- to low-carbon energy resource, depending how it is produced. Economywide demand for hydrogen would be the most economical scenario; building a bulk underground storage and pipeline transport system just for the power sector would be costly.

Pipelines are expensive and slow to build. But without them, the cost and logistics of statewide use of hydrogen for power grid reliability would be prohibitive.

The greatest near-term opportunity appears to be in upstate New York, if low-cost or curtailed renewable electricity could power hydrogen production co-located with geologic storage.

However, there may not be excess renewable electricity to generate hydrogen in 2040, and the cost of hydrogen is expected to be significantly higher than natural gas.

Biofuels

Renewable natural gas (RNG) and renewable diesel (RD) are the biofuels most relevant to the power sector because they are drop-in replacements for natural gas and distillate fossil fuels.

RNG has relatively few infrastructure needs, but its feedstocks are limited and are required for decarbonization of other sectors. So RNG would most likely serve as a peaking resource. The air-quality impact of RNG combustion depends on whether it is evaluated by net emissions, which are zero or close to zero, or by gross emissions, which are similar to natural gas.

RD may be particularly important to New York’s grid as it shifts to a winter-peaking system. But it is expected to be significantly more expensive than fossil distillate, and it is less efficient than RNG in combustion turbines.

Biofuels and hydrogen have near-term supply constraints, but the availability of hydrogen has the potential to outstrip biofuels because of the finite supply of biofuel feedstocks.

Advanced Nuclear

Nuclear reactors are expensive; operating them at a high capacity factor is more economical. So while advanced reactors are expected to be capable of more flexible operation than today’s conventional fleet, they are likely to remain baseload power.

Developing any new nuclear generation in New York by 2040 will require early and careful planning, as the timeline may stretch a dozen years per facility, unless federal intervention or economies of scale speeds up the regulatory and construction process.

Carbon Capture and Storage

CCS can be used on a natural gas-fired peaker plant, but it is best used on baseload power plants because it is expensive and less efficient on an intermittent basis.

CCS would require significant buildout of transport and storage infrastructure that does not exist in New York. Such an ecosystem would face challenges in regulation, permitting and public acceptance but could benefit hard-to-decarbonize industrial applications.

Even a carbon capture rate of nearly 100% would not make a significant reduction in upstream emissions totals as tallied by New York’s greenhouse gas accounting system.

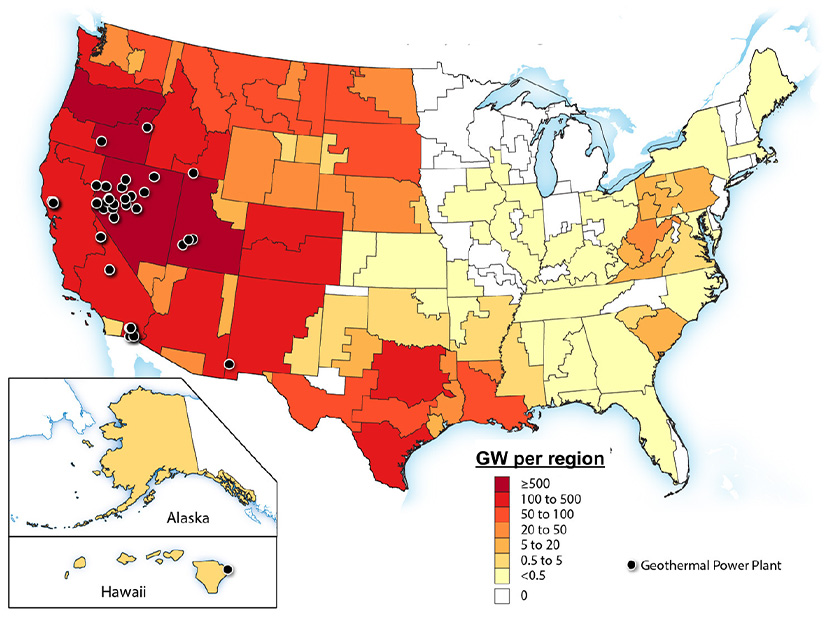

Geothermal

The geological landscape of New York is largely unexplored for its geothermal power potential, but the potential is believed to be quite low — less than 1 GW by 2040 — using existing technology.

But in the longer term, with continued technological innovation, there is a theoretical potential for greater use of the earth’s heat to generate electricity in New York. The cost of such an effort is highly uncertain.

Long-duration Energy Storage

Short-duration storage (less than 10 hours) presently can meet most grid-balancing needs, but greater reliance on renewable power will require larger capacities and longer durations of storage.

The report examines 18 electrochemical, mechanical and thermal energy storage technologies capable of operating for durations greater than 10 hours.

Electrochemical and mechanical technologies generally are more ready for deployment. Electrochemical technologies are more modular and can provide more grid services but come with safety considerations, higher costs and shorter lifetimes. Thermal technologies potentially are useful for industrial decarbonization.

All come with round-trip efficiency losses, and some with standby losses.

Emerging technologies must be assessed to mitigate any risks as they move from early development to deployment.

Electricity market design changes are needed to support market-based deployment of long-duration storage.

Virtual Power Plants

VPPs could serve as a key intermediary between flexible distributed energy resources and load-flexible appliances.

A recent study showed VPPs could reach 8.5 GW of flexibility potential in New York by 2040, a cost-effective approach to balancing supply and demand.

VPPs carry low capital costs and short lead times, but realizing their potential would require improving customer recruitment and participation; standardizing communications and market interfaces; and addressing metering and telemetry costs. Programs with easier enrollment and reduced user interface are expected to have the greatest impact.

Where to Begin

The report identifies several no-regrets actions the state can take to set the stage needed for its 2040 goals:

-

- Do not overly rely on one technology; pursue a diverse portfolio.

- Start early.

- Invest in grid-enhancing technologies to reduce the need for backstop resources.

- Invest in innovation.

- Develop strategies across industries to overcome infrastructure hurdles.

- Engage early with developers, end users and other stakeholders.

- Model a range of costs and performance attributes of technologies to deploy.

- Reassess options regularly and remain flexible as new options become available.