By Christen Smith

Decarbonization of the energy sector holds the key to reversing greenhouse gas emissions and preventing a catastrophic rise in global temperature, the U.N. Environment Program said in its annual Emissions Gap report published Tuesday.

And the increased electrification of economies — powered by renewable resources — will be vital to that effort, UNEP found.

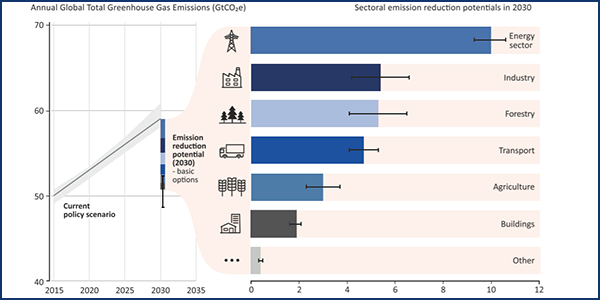

National-level climate policies have so far been unable to offset emissions levels over the last decade and now, UNEP warns, a 7.6% annual reduction through 2030 is necessary to limit the world’s temperature increase to just 1.5 degrees Celsius — in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

“When looking back at the 10 years we have prepared the Emissions Gap Report, it is very disturbing that in spite of the many warnings, global emissions have continued to increase and do not seem to be likely to peak anytime soon,” said John Christensen, director of UNEP DTU Partnership. “The reductions required can only be achieved by transforming the energy sector.”

UNEP’s analysis identified six key areas that carry the most potential for decarbonization and limiting emissions to 21 gigatons of CO2 equivalent in 2030: solar and wind energy, efficient appliances and passenger vehicles, afforestation and stopping deforestation. Although concentration on these strategies will get the world much closer to its temperature goals, UNEP said the reductions will still fall short of 32 gigatons necessary to keep on track for a 1.5-degree Celsius rise.

“The good news is that since wind and solar in most places have become the cheapest source of electricity, the main challenge now is to design and implement an integrated, decentralized power system,” Christensen said.

‘Easy Win’

UNEP calls the expanded use of renewable power to drive electrification an “easy win” in the short-term effort to reduce CO2 emissions. It says the “three pillars” of decarbonizing the power sector include a “vast expansion” of renewables, along with a “smarter and much more flexible” grid and a “huge” increase in the number of products and processes that run on electricity — particularly for transportation and industry.

The report points to promising trends for electrification, noting that needed technologies already exist. Growing investments in renewable energy spawned capacity additions worldwide of 50 GW for wind and more than 100 GW of solar in 2018 — outpacing net additional power generation of nonrenewable resources for the seventh year in a row, UNEP said. Global investment in renewables that year reached US$272.9 billion, about triple the spending on new gas- and coal-fired resources combined.

“The main enabler for the accelerated deployment of renewable energy in the last decade has been the continued and rapid decline in capital costs,” the report said. “In most parts of the world today, renewables have become the lowest-cost source of new power generation and are generally competitive without incentives when directly compared with fossil alternatives.”

But while renewables have increased their share of global generation to 12.9%, helping to avoid about 2 gigatons of CO2 emissions, UNEP insists adoption must grow at six times the current rate to meet climate targets.

The agency points to a key hurdle in achieving that level of adoption: the need for investments in flexible resources equipped to respond to the short- and medium-term variability of wind and solar.

“Conventional power plants, gas-fired generation and hydropower with reservoirs are currently the predominant sources of system flexibility in modern power systems, but other options will increasingly become important such as electricity networks, battery storage, distributed energy resources and enhanced predictability,” the report said.

UNEP points to findings that show the cost of flexibility needed to integrate renewables is “generally quite small” at US$5 to $13/MWh, with costs rising on systems with more inflexible coal or nuclear units. The report notes governments and grid operators can take measures to support flexibility, including modifying legal and regulatory frameworks, market rules and system operation protocols.

Other major challenges to cleaner generation persist. Developing countries reliant on fossil fuels must take decarbonization slower so as to limit socioeconomic impacts while other nations must take bigger swings toward reductions to keep the temperature goal within sight, UNEP concluded. G20 countries account for 78% of all worldwide emissions, but only five have committed to long-term zero emissions targets.

“Our collective failure to act early and hard on climate change means we now must deliver deep cuts to emissions — over 7% each year, if we break it down evenly over the next decade,” said Inger Andersen, UNEP’s executive director. “This shows countries simply cannot wait until the end of 2020, when new climate commitments are due, to step up action. They — and every city, region, business and individual — need to act now.”

“We need quick wins to reduce emissions as much as possible in 2020 … we need to catch up on the years in which we procrastinated,” she added. “If we don’t do this, the 1.5 degree goal will be out of reach before 2030.”

Ignoring the Alarm

UNEP’s report provided a host of recommendations to several G20 countries — Argentina, Brazil, Japan, China, India, the European Union and the United States — that could accelerate emissions reductions. Some of the policy changes include eliminating subsidies for fossil fuel generation, phasing out coal plants, supporting the electrification of vehicles and use of public transportation and implementing carbon pricing.

Even with energy-specific taxes and carbon policies currently in use, half of fossil fuel emissions are not priced at all and less than 10% are priced at an appropriate level to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius, UNEP said.

“For ten years, the Emissions Gap Report has been sounding the alarm — and for ten years, the world has only increased its emissions,” said UN Secretary-General António Guterres. “There has never been a more important time to listen to the science. Failure to heed these warnings and take drastic action to reverse emissions means we will continue to witness deadly and catastrophic heatwaves, storms and pollution.”

Robert Mullin contributed to this article.