PJM’s Independent Market Monitor on Tuesday defended its conclusion that ratepayers are likely to see cost increases in jurisdictions that exit the RTO’s capacity market and adopt the fixed resource requirement (FRR) option.

PJM IMM Joe Bowring | © RTO Insider

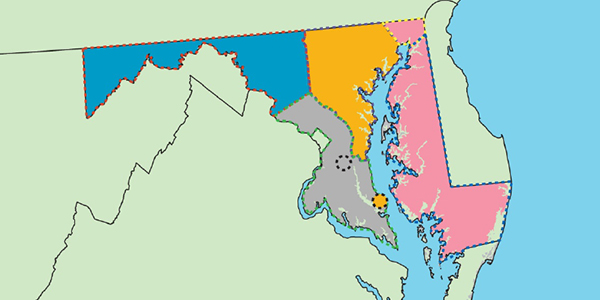

Regulators in Illinois, New Jersey and Maryland have said they are considering the FRR option in response to PJM’s MOPR Quandary: Should States Stay or Should they Go?)

“Based on conversations I’ve have had — both public and private — with those who are pursuing FRRs, they’re increasingly recognizing … that the costs are likely to be higher under an FRR than under the competitive market,” Monitor Joe Bowring said during Raab Associates’ Energy Policy Roundtable in the PJM Footprint webinar Tuesday.

States can require their utilities to make the FRR election. The FRR entity must provide adequate capacity for all load-serving entities in its territory regardless of the existence of retail choice, Bowring said. LSEs are required to pay the FRR entity based on either a state-mandated compensation mechanism or — in the absence of a mechanism — on the Rest of RTO capacity price, he said.

The Monitor issued an analysis on the impact of Exelon’s Commonwealth Edison leaving the capacity market for an FRR in December and one on Maryland’s options April 17.

The ComEd report’s first scenario concluded net load charges would increase 23.6% if ComEd procured all of its capacity obligations outside of the BRA at the offer cap — $254.40/MW-day — rather than the $195.55/MW-day clearing price in the 2021/22 Base Residual Auction.

Maryland Public Service Commission Chair Jason Stanek | Md. PSC

In a second scenario, the Monitor calculated that ComEd’s load charges would decrease 5% if the price negotiated for its capacity were equal to the locational deliverability area’s (LDA) clearing price. The report contended the first scenario was more plausible, “given Exelon’s assertions that the current total revenue from energy, ancillary and capacity markets is not adequate for its nuclear plants.”

Only one of six scenarios in the Maryland analysis showed possible cost savings for Maryland ratepayers (5.4%), while the other scenarios saw increases of 5 to 43%. (See “Monitor: Maryland FRR Likely to Increase Capacity Costs,” FERC: RGGI, Voluntary RECs Exempt from MOPR.)

FRR “is not an easy exit ramp to choose,” said Maryland Public Service Commission Chair Jason Stanek, who also appeared on the panel on pursuing state clean energy policies under the expanded MOPR.

Lower Reserve Margin

But Rob Gramlich, president of Grid Strategies, said FRRs won’t necessarily raise costs. “The cost-reducing effect of FRR is known — the lower reserve margin. All other things [being] equal, that clearly has the effect of reducing prices,” he said. The FRR unforced capacity (UCAP) obligation for the ComEd zone is 23,385 MW — about 2,700 MW (10.4%) less than ComEd’s requirement of 26,112 MW under the BRA.

Gramlich said the Monitor’s analyses are based on improper assumptions, including that generators outside the LDA would be paid more under FRR than what they would earn in the PJM auction. Half the scenarios assumed prices at the offer cap for the applicable LDA. The $254.40/MW-day in the ComEd LDA is 30% above the $195.55/MW-day clearing price in the 2021/22 BRA.

He said the analyses only look at the next BRA and assumed “MOPR has no cost impact going forward, thus finds no savings” under FRR.

Gramlich also said the Monitor ignores the flexibility in FRR for portfolio-based penalties. Four-hour storage, which gets little capacity value in the BRA, can be included in FRR entities’ portfolios to avoid performance penalties, he said.

“I’m not necessarily advocating for FRR,” Gramlich said. “There are good and bad FRR approaches. … My point is nobody should be surprised that states are trying to accomplish their own objectives, and I think the rhetoric around FRR meaning a retreat from markets is not accurate. And studies saying FRR necessarily raises costs [are] also not accurate.”

Exelon also has challenged the Monitor’s analysis. Exelon’s Jason Barker told PJM stakeholders in February that the ComEd analysis was not “a credible or useful tool for understanding the value of an FRR for Illinois customers.” (See Exelon Challenges PJM Monitor’s ComEd FRR Analysis.)

Bowring was unyielding Tuesday. He said his firm’s reports are not attempting to predict what the final capacity prices would be under FRR but to give low and high price estimates of the economic impacts on consumers. He said the reports are conducted with detailed analysis using defined input assumptions so others can evaluate the results.

He said the increase in costs under FRR would be even larger once state subsidies to nuclear and renewable resources are factored in. “It appears to be demonstrably cheaper to stay with the markets, and if you need to do additional subsidies on the side, you can do that” for a lower total cost than FRR, Bowring said.

Market Power

Bowring said FRR would be a weaker variant of cost-of-service regulation and noted that imports into capacity market delivery areas are limited by capacity emergency transfer limits, which he said are relatively low compared to capacity requirements. The concentrated ownership of capacity that can meet the state’s capacity requirements gives local generation owners market power.

“It’s the state bargaining with monopolists who have better information [and] more knowledge about the cost of the resource and the nature of the resource,” Bowring said. “It’s not an equal negotiation. So basically, you’re giving market power to the generators in the FRR, and that’s the really critical point.”

He noted that generators within an FRR area are not required to participate, giving them leverage over pricing. “If you don’t think you’re going to get a fair price — a price equivalent to what other people are being paid for capacity — then you don’t have to participate and the FRR can’t occur,” he said.

Capacity Transfer Rights

Bowring said that while Gramlich pointed out that the reliability requirement would be lower in an FRR, he ignored that capacity transfer right (CTR) payments would go down significantly, causing prices for consumers to rise.

Rob Gramlich, Grid Strategies | © RTO Insider

Gramlich insisted the CTR payments are “not a factor.”

“That number is identical to the … excess payments [the Monitor] assumes for that external generator to sell into a constrained area. … That’s not the case if you pay that external generator a competitive price.”

Gramlich said the Monitor’s market power concerns are “partially contrived by the assumption that states would prefer to choose resources that are internal to their state. Well, the state doesn’t have to do that. … In some ways the analysis assumes bad FRR design by choosing the generators, thereby conferring market power to them rather than competitively soliciting power from internal and external generators.”

New Jersey

Gramlich said the expanded MOPR has been “the worst thing since the California flawed initial market design [to] the cause of RTOs and competition,” saying it will result in almost 32 GW of unmet state renewable portfolio standard demand by subjecting almost 8,800 MW (UCAP) of nuclear and renewable resources to the rule.

The shortfall will increase by 2035 with the addition of 7,500 MW of offshore wind from New Jersey and again with Virginia’s adoption of a 100% clean energy standard, he said. (See Va. 1st Southern State with 100% Clean Energy Target.)

The New Jersey Board of Public Utilities is accepting comments until May 20 on alternatives to the state’s participation in the capacity market, with reply comments due June 24 (Docket EO20030203).

Bowring said a report on New Jersey’s FRR options should be released in a few weeks. He declined to speculate on its findings, saying it would be market-sensitive information. “I doubt it would be very different” from the previous analyses, he added.

New Jersey’s contract for offshore wind — a long-term contract with built-in escalators — “sounds a lot like some of the old PURPA [Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act] contracts that were signed that ended up costing New Jersey customers billions of dollars in excess of market value,” Bowring said.

Maryland’s Approach

Stanek said the Maryland PSC has been reviewing the Monitor’s analysis for the state and is working with its legislators in Annapolis to determine its best move. He said it is also closely looking to see what actions Illinois and New Jersey take.

“We’re taking a slower approach,” he said. “We would like to see what the next BRA auction results are. One thing we can agree on is that they’re not going to be terribly out of line compared to the last auction.”

Beyond that, he said, there are no guarantees.

“I don’t believe that we’ve made a good use out of the past two years fighting FERC, working on this MOPR. I think all parties — whether you’re [the] renewable sector, you’re a state regulator, you’re a … merchant generator — I don’t foresee that this current capacity market … is going to continue in the current state. So, we need to use our resources to figure out what comes next. True, we’ll have a few more BRAs in the coming future. But we need to plan for the next phase so that states can pursue their public policies.”

Returning to the Bargaining Table

Sarah Novosel, managing counsel and senior vice president for government affairs for Calpine, said she was grateful that FERC acted on rehearing only four months after its December order, allowing those who oppose it to make their case before the appellate courts.

Sarah Novosel, Calpine | © RTO Insider

“I’m hopeful that it’s now going to allow the legal issues to be put into the courts where they belong — they need to be sorted out by the court — and really allow FERC and parties to focus on the compliance process. Because that’s really what we need to do, is … get the compliance order issued and get the auctions started again.”

Novosel said her company — which filed the FERC complaint that resulted in the December order — is open to additional negotiations to address concerns over renewables.

“Calpine, and I think other generators, are open to coming back to the bargaining table,” she said. “We’ve got the order now, and we’ve gotten to the point where we really do need to get some data from the auctions. … Let’s see where the prices are heading.”

One way for offshore wind to participate under MOPR, she said, would be for PJM to adopt something similar to New England’s Competitive Auctions with Sponsored Policy Resources (CASPR) two-stage construct. Under CASPR, ISO-NE will clear the Forward Capacity Auction after applying the MOPR to new capacity offers to prevent price suppression. In the second Substitution Auction, generators nearing retirement that cleared in the primary auction could transfer their obligations to subsidized new resources that did not clear because of the MOPR.

Carbon Pricing

Bowring, Gramlich and Novosel all expressed support for carbon pricing, which was the subject of a second panel.

Susan Tierney, senior adviser for the Analysis Group, discussed her analysis on NYISO’s carbon pricing proposal, which she said could be only one of the many tools the state will need to meet its ambitious goals under the 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act: 70% of electric supply from renewables by 2030 and 100% from zero-carbon resources by 2040.

Solar will have to triple in five years, and energy storage will have to grow tenfold in the next decade, she said. Meanwhile, the state expects to lose two of its nuclear generators in the next few years.

“It took 60 years to get to 28% renewables [penetration]. So, this is a huge lift that is going to have to take place,” she said. “New York should really [use] every tool under the sun. … No one knows how they will accomplish these goals, so innovation is absolutely critical.”

Tierney said passage of the law “changed the tone of [NYISO’s] stakeholder discussions in a very big way,” broadening support.

The ISO is now awaiting state action on its plan. (See NYISO Focus Turns to Grid ‘Transition.’)

“The NYISO has always said that … taking a proposal to FERC would really require some signal from the state — the politicians — that there was interest in having FERC entertain this,” she said.

Discussions with New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s office have been derailed by the coronavirus pandemic, leaving timing uncertain.

“What’s going to happen may also be timed to the next elections and new appointments to FERC,” she said.

Emanuel Bernabeu, PJM’s director of applied innovation and analysis, discussed the RTO’s efforts to model carbon pricing in parts of its footprint and ways to limit leakage, which it shared with stakeholders in February. (See PJM Panel Weighs Impact of Pa., Va. Joining RGGI.)

Bernabeu said the PJM’s next steps will be to model RTO-wide carbon pricing and higher prices — $25/ton and $50/ton, compared with the $7/ton and $15/ton modeled previously. He cautioned that the previous results cannot be extrapolated. “Everything is very highly nonlinear,” he said.

Karen Palmer, director of Resources for the Future’s (RFF) Future of Power Initiative, noted that Virginia is planning to join the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative in 2021. “That’s a big addition,” she said. “It’s going to substantially increase the number of emitting generators under the RGGI cap.”

Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf has said he wants the state to join RGGI also, but he is facing opposition from the Republican-controlled legislature. (See Critics: Pa. RGGI Hearing Stacked with Detractors.)

“We’ve done some modeling showing that if Pennsylvania wants to do a cap and trade, joining RGGI is a good idea because it’s going to be cheaper than going it alone. And also … there are ways you can target revenues from the allowance auctions that could help reduce emissions leakage.”