ISO-NE External Market Monitor David Patton delivered highlights from his 2019 assessment of the RTO, comparing its markets with others in the Eastern Interconnection and making several recommendations.

Patton, president of Potomac Economics, related concerns about the current Forward Capacity Market and plugged the benefits of a prompt capacity in the context of improving coordinated transaction scheduling with NYISO.

“We think the pros of a prompt capacity market outweigh the cons,” Patton told the New England Power Pool Participants Committee on June 23. “In other words, we tend to think prompt capacity markets perform better than forward capacity markets, and the large demand forecast errors that have occurred In New England highlights one of the many concerns of a forward capacity market.”

[Note: Although NEPOOL rules prohibit quoting speakers at meetings, those quoted in this article approved their remarks afterward to clarify their presentations.]

However, he did not recommend eliminating the FCM because the benefits of doing so do not clearly outweigh the market disruptions it would cause. But he did recommend that ISO-NE replace the descending clock auction with a sealed-bid auction to improve competition in the Forward Capacity Auction.

Patton also recommended improving the minimum offer price rule by: eliminating performance payment eligibility for units subject to the MOPR; capping the minimum offer price at the net cost of new entry; and exempting competitive private investment from the MOPR.

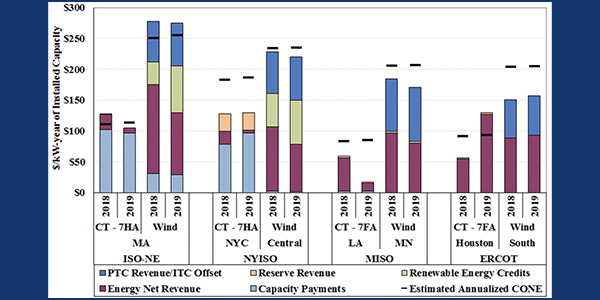

A comparison of net revenue across various regional electricity markets showed that a well functioning wholesale market helps establish transparent and efficient price signals, which in turn influence the locations and technologies of new projects, according to the EMM’s report.

In New England, net revenues have been close to the levelized new entry costs for combustion turbines, but this will not continue in the future as capacity prices fall over the next few years, the report said. With tax credits and renewable entry credits, the markets are providing more than sufficient revenues for wind resources. Wholesale market revenues will continue to play a key role in motivating entry of flexible units that help integrate policy resources and prompt the retirement of inflexible units.

The EMM also recommended the RTO modify allocation of “economic” net commitment period compensation (NCPC) charges — the payment made to market participants that don’t recover their effective offer costs — to align it with cost causation, and pursue improvements to the price forecasting that is the basis for CTS with NYISO.

An uplift rate of $2 to $3/MWh over the past three years generates millions of dollars in day-ahead NCPC payments, but “the shocking number is the number of hours, almost half the hours of the year, when commitments are being made to supply spinning reserves,” Patton said.

“This signifies that both our prices and our compensation in the day-ahead is not very efficient when it comes to the types of units that are supplying the spinning reserve product,” he said. “It also tends to undermine the energy price because, to the extent that costs are being incurred to meet the spinning reserve requirements, those costs should be reflected in energy prices.” However, Patton indicated that the RTO’s Energy Security Improvements (ESI) initiative will address these concerns.

When asked about how recent reductions in load forecasts should be factored into the capacity market requirements, Patton said that “the general principle is that you should do everything you can to make your installed capacity reserves forecasts as accurate as possible, recognizing that there are Tariff requirements and tradeoffs where the ISO has to publish what the requirements are in advance of the auction so that people can … offer into the auction.”

Further recommendations are to modify the performance payment rate to rise with the reserve shortage level and not implement the remaining planned increase in the payment rate; and consider modifying the capacity compensation of energy-limited resources to be consistent with their reliability value.

The Monitor also recommended that the RTO require the use of the lowest-cost fuel or configuration for multiunit generators when they are committed for local reliability.

BPS Reliability Perspectives for 2050

NERC CEO Jim Robb gave the PC a look at various bulk power system reliability perspectives at midcentury, with key issues being the timing of technology development and deployment (especially batteries), the pace of deep electrification and the regulatory treatment of natural gas.

“The one challenge our industry has is that we’re enormously reactive,” Robb said. “We are great at responding to an event and figuring out what went wrong and changing it, but we are not great at heading events off before they happen, because it’s hard to motivate people to make hard choices when they don’t feel them very present.”

Bruce Ho of the Natural Resources Defense Council referred to the need for increasing system flexibility in which load follows generation — rather than just generation following load — as the country gradually moves to a fully decarbonized grid that relies on variable energy resources like wind and solar.

“I’m curious what you see as the role in the other direction, with more dynamic loads that follow supply,” Ho said, citing the importance of demand response. “What role do you see on the demand side, and do you have any thoughts on how markets and reliability standards might need to adapt to incorporate and compensate that dynamic load?”

“We need to rethink so many things, because I actually have a bias of thinking of the electric system serving load,” Robb said. “And you’re right; as Mark Lauby says — who’s our chief engineer and the smartest technical guy I know on this stuff — that concept is increasingly flawed.”

Planners need to expand their thinking about the grid beyond a linear relationship between the bulk power system, the distribution system and end users, he said. It would be wrong to describe them as being “integrated,” Robb said.

“Really, they’re all interdependent,” he said. “When I talk about the new models, the new operating paradigms, I think those issues need to be brought in as much as anything else. Demand response can play a really important role, but will it be there on the fourth day of the heat wave? I have a little bit of a [former PJM CEO] Terry Boston view of the world in that I like iron in the ground, because I know I can do something with it.”

Robb cited cybersecurity as a constant issue and said he does not like the term “Internet of Things,” preferring to think of it as the “Internet of Threats.”

Investing in the Future

Scott Kushner, managing director of Boston-based John Hancock Infrastructure Investments, discussed how he and his team decide where to invest in the electric power industry and how changing public policy affects such decisions.

Of the firm’s $30 billion in assets under management, approximately 30% is invested in private equity investments, while the remaining 70% is in investment-grade, long-term, fixed-income debt products, Kushner said.

“We lend to utilities; we’ve lent to projects, power plants of all technologies, all fuel sources; but certainly lately renewables has become a very big piece of what we’re looking at on both the debt and equity side,” Kushner said. “One of the main drivers of that, if you look at what an insurance company likes to invest in, is the lower-risk stuff, the stuff with longer-term contracts.”

On lowering the cost of capital, James Daly, vice president of energy supply at Eversource Energy, asked whether Kushner preferred programs with more revenue certainty or those dependent on merchant revenues.

“It certainly helps from an institutional investor standpoint,” Kushner said. “I would say that SREC 1 and SREC 2 [solar renewable energy credits] in Massachusetts worked really well, but certainly when we’re looking at the cost of capital for the SMART [Solar Massachusetts Renewable Target] program, which has the longer-term feed-in tariff like contracts, the cost of capital has come down even lower.”

Whether because of highly structured state programs or just the evolution of time and more investors starting to get comfortable in the clean energy space, “certainly the longer the contract, the more certainty in it, there’s no denying that will lower the cost of capital,” Kushner said.

“It seems that the capacity market in New England, with the seven-year lock rate available for new resources, is able to provide sufficient revenue certainty and risk reduction to make financing terms attractive for gas generation, but it doesn’t have the comparable impact for financing of renewable generation because those resources get the majority of their revenue from the energy market, which has no similar long-term certainty,” said Abigail Krich, president of Boreas Renewables.

“While state solicitations for long-term contracts and programs like SMART are filling in that gap to provide comparable revenue certainty to renewable resources, if the wholesale market were modified to be able to supply a similar level of revenue certainty to renewable resources, would those long-term contracts and policy commitments for renewables still be needed in order to be able to finance them?” Krich said.

There’s a place for both gas-fired generation and renewables in the market, Kushner said.

“If the market were to shift from these longer-term contracts to something like the capacity market for fossil fuels, which gives these projects price certainty for maybe five to seven years, the projects absolutely will get financed,” Kushner said. “It just depends on who’s going to actually finance them and what the ultimate cost of capital is.”

Problem Trio

Rutgers University professor Frank Felder, who teaches electricity policy and market structures, presented a thesis posing three types of problems that market operators and public officials must address: political economy, economic/regulatory and engineering.

“They are really three subsets of the same problem,” said Felder, director of the Rutgers Energy Institute and the school’s Center for Energy, Economic and Environmental Policy.

Deep decarbonization is a political economy problem because it concerns jobs, costs and economic policy, which interact with the economic and regulatory problem, he said.

“Whether an entity is regulated, or in a market environment, or in an integrated utility environment, there are economic and regulatory incentives that shape the decision-making, and in particular with long-term loan capital assets, you have a variety of problems, such as asymmetric information,” Felder said.

For example, an offshore wind developer knows more about the cost structure of a power purchase agreement than the regulator signing off on the deal, he said.

Engineering comprises both optimization and system-control problems, Felder said.

Political, economic and reliability difficulties are likely to arise unless these three types of problems are addressed in an integrated and consistent manner, he said.

“Massachusetts is really committed to trying to find a market-based solution to integrate clean energy,” said Matthew Nelson, chair of the state’s Department of Public Utilities. “We know that’s not going to be easy.

“Massachusetts has been very supportive of carbon pricing, so we’ve supported the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. We have initiatives [that encompass more than] energy, like our state-specific Clean Energy Standard, and the Transportation Climate Initiative, but we’re not so interested in a FERC-jurisdictional carbon pricing — that concerns us,” Nelson said.

Massachusetts wants to ensure that a carbon price brings clean resources online and that it works with existing state policies, he said. Meanwhile, “other states in New England are in very different places on this one as well.”

“Where we’re all aligned, at least on carbon, is we don’t have any interest in a federal-based carbon price that would prevent states from achieving their individual goals,” Nelson said. “How is the price set? How is it priced accurately? Those are big, fundamental questions that bother individuals.” (See Study: $25 Carbon Price Needed to Meet Goals.)

Speaking to RTO Insider after the meeting, Nelson said, “Specifically here, what I think is important is who is setting the price and that process, because obviously that’s a big decision and will influence the outcome. I feel that’s a question we need to answer before states would be supportive.”

Some states don’t have clean energy targets and don’t think that increasing the price of carbon is actually what they want to achieve, he said.

“At this time, I just don’t think that a new carbon price adder outside of RGGI is politically feasible for all six states,” Nelson said. “But we’re not scared to talk about the data, what that data achieves, where the price is set. I think we have to have the conversation around what the numbers are and what we’re paying through different processes, to understand the different policy decisions we’re making.

“We have aggressive clean energy targets in Massachusetts,” he said. “I know that we’re going to need more clean energy to come online, and most of the need will be met through load growth through some of our policies around decarbonization of transportation, of buildings. And continued out-of-market contracts still have some inherent drawbacks, especially in the long-term scale we’re talking about.”