FERC last week found that the tax relief granted to a solar farm being constructed in Virginia does not fall under PJM’s minimum offer price rule (MOPR) or qualify as a state subsidy (EL21-35).

Hollow Road Solar, a 20-MW qualifying facility being developed in Frederick County, filed a petition with the commission seeking confirmation that it will not be subject to the MOPR in the upcoming Base Residual Auction (BRA) for the 2022/23 delivery year scheduled to take place in May. The project sought a determination that local property tax relief granted by a Virginia pollution control statute is exempt from the definition of a state subsidy under the MOPR.

The facility’s developers brought the petition to FERC after seeking guidance from PJM. They said the commission specifically exempted “general industrial development” and “local siting statutes” from the definition of state subsidy in recent MOPR orders, saying that comparable support was generally publicly available and not “tethered to” or “directed at” PJM’s wholesale capacity or energy markets. (See FERC Acts on PJM MOPR Filing.)

Hollow Road argued that the Virginia statute should be exempt from the MOPR because its benefits are available to all businesses and not “nearly directed at or tethered” to the “new entry” or “continued operation of generating capacity” in the PJM capacity market. It said the subsidy is focused on the control and abatement of pollution in Virginia.

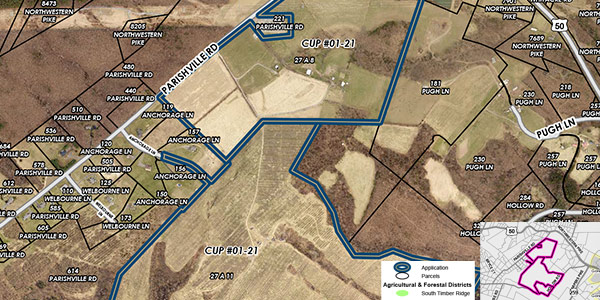

Hollow Road Solar project | Frederick County Planning & Development

In its response, PJM said it previously examined the statute and proposed to stakeholders that it met the definition of a state subsidy under the tariff. The RTO said provisions of the statute have separate sections specifically addressing property tax exemption rules that applied only to standalone solar facilities.

In its December 2019 MOPR order, FERC said the definition of state subsidy focuses on out-of-market payments that “squarely impact the production of electricity or supply-side participation in PJM’s capacity market” and does not include “every form of state financial assistance that might indirectly affect commission-jurisdictional rates or transactions.”

The commission also allowed an exclusion for certain forms of state support that are “available to all businesses and not nearly directed at or tethered to the new entry or continued operation of generating capacity in the federally regulated multistate wholesale capacity market administered by PJM.”

In Thursday’s order, FERC said the Virginia provisions should be excluded from the definition of state subsidy because they apply “broadly to certified pollution control equipment and facilities” and not just those used in electricity generating facilities. Under the statute, certified equipment and facilities include “any property, including real or personal property, equipment, facilities or devices, used primarily for the purpose of abating or preventing pollution.”

“We find that the Virginia pollution control statute is generally available and not nearly directed at or tethered to wholesale market participation, and therefore excluded from the definition of state subsidy,” FERC said.

“The reference to solar facilities cited by PJM does not require a contrary conclusion,” the commission said. “Solar facilities are included as part of a non-exhaustive list of example technologies that also includes a wide range of equipment unrelated to electric generation or the PJM capacity market — everything from certain on-site sewage systems, thermal energy storage devices and ‘equipment used to grind, chip or mulch trees [and] tree stumps.’”

PJM’s Independent Market Monitor argued that the fact that some nonpower production entities may be eligible for tax relief under the law is “irrelevant for purposes of the MOPR” and that providing an exclusion for the statute would “create a loophole undermining implementation of the MOPR.”

The commission disagreed.

“The definition of state subsidy was never intended to cover every form of financial assistance,” FERC said. “Excluding the Virginia pollution control statute from the definition of state subsidy will not affect the applicability of the MOPR to those subsidies that it was intended to address.”

Commissioner Views

FERC Commissioner James Danly provided the lone vote against the petition, dissenting strongly in a separate statement.

Danly faulted the commission’s finding that the Virginia law’s subsidy is “generally available” because it includes other technologies such as sewage systems and tree chippers. He said most of those technologies had been included in the statute since 2003, but solar equipment was added by separate bills in 2014 and 2016.

The “overwhelming preponderance of statutory text” in the statute involves solar facilities, Danly said, including whole sections devoted solely to solar facilities and creating conditions for those facilities to receive tax relief.

“Our order today thus allows a subsidized solar facility to bypass the PJM minimum offer price rule and bid into the PJM Base Residual Auction below its actual costs,” Danly wrote. “The consequences for PJM’s capacity market prices are obvious. Every existing capacity resource in the applicable zone will suffer artificially low prices caused by new resources ‘competing’ on an uneven playing field.

“Many disagree that PJM should mitigate new renewable resources subsidized by the states, but the proper course is to change the mitigation rules (if in fact they need to be changed) rather than to declare that tax relief overwhelmingly directed at solar facilities is not really a subsidy directed at solar facilities because the tax relief may also be available to a wood chipper,” he said.

Commissioner Neil Chatterjee expressed appreciation for Danly’s reasoning and his “certitude” on the issue but said the majority opinion offered a “well explained, thoughtful analysis” and that he was “pleased” to support the ruling. He said Hollow Road’s petition gave the commission the opportunity to apply the MOPR rule “in a manner that’s both consistent with our prior findings and reflective of plain old common sense.”

“We’ve made clear along the way that the MOPR is not intended to address generally available state assistance, nor should it reach every program that may indirectly affect the economics of a particular resource,” Chatterjee said.

Technical Conference

FERC issued the ruling just before hosting a technical conference tomorrow at which it will lead stakeholders in a discussion of the role of capacity markets in Eastern RTOs and ISOs.

The first panel will explore the growing interplay between state policies and capacity markets and examine the long-run impact of continuing with the status quo MOPR framework.

A second panel will zero in on the implications of continuing the status quo MOPR in the PJM capacity market and consider the viability of the market with current rules as state policies continue to impact resources. FERC officials want to determine whether PJM can retain its responsibility for resource adequacy as states take measures to create their own energy resource mix.

A final panel will look at alternative approaches for the PJM capacity market and its evolution with changing state policies.

MOPR’s Outside Viewpoints

In a recent report titled “The Numbered Days of PJM’s MOPR-Ex?”, ClearView Energy Partners said PJM could change its market rules as early as this summer. Those changes could include a reversal or narrowing of the MOPR to be approved in time for the BRA for the 2022/23 delivery year scheduled to take place in December.

“We think that a smaller, more ‘residual’ capacity market looms as a real possibility over the next several years, unless an overarching federal program (such as a clean energy standard or substantive [greenhouse gas] limits) is enacted,” ClearView wrote in its report.

ClearView said it may be easier for PJM to allow its states to take on their own decarbonization goals through “bilateral arrangements” rather than attempting to create a solution for all the states in the RTO.

“Unless or until federal policy overtakes individual state agendas on decarbonization, meeting disparate needs through a centralized market appears destined to be problematic,” ClearView said.