Tony Clark | Wilkinson Barker Knauer

Tony Clark | Wilkinson Barker Knauer

The energy policy hive is having a healthy discussion of late taking up a question we raised 18 months ago. (See Is Decarbonization an ‘Existential’ Challenge for RTOs?) Can the single marginal price construct in ISO markets continue to work effectively given important changes to generation technologies?

ISOs and proponents of the status quo have risen to defend the single locational marginal price (LMP), at least when applied in energy and related ancillary service markets. They assure that reform and expansion of the construct is possible to meet new challenges, and they quickly dismiss any notion of a fundamental rethinking. Their arguments extolling LMP are not wrong; they’re misplaced.

And they’re the same arguments raised since LMP was introduced. Indeed, a recent report, prepared by Professors William Hogan and Scott Harvey for the NYISO, walks step by step through more than 30 years of LMP history to conclude that:

economic theory and extensive practical experience demonstrate why the real-time locational marginal price is the only real-time pricing system that supports an efficient wholesale electricity market.

Vince Duane | PJM

Vince Duane | PJM

In comments this month to FERC and in reply to our prior writings, PJM’s market monitor endorses Hogan and Harvey’s recent paper. Much of the paper and comments in support simply recite (once again) the benefits that LMP offers as an efficient mechanism to dispatch, balance and schedule generation resources, price transmission congestion and reveal locational incentives and signals. We don’t disagree.

LMP is great — let’s get that out of the way. Our criticism is not with LMP in theory. Instead, we’re seeking a dispassionate assessment of how LMP is actually performing today and its prospects for success in the future. Since its inception, the single marginal price market for energy has delivered on much of its promise, although only a zealot would deny its limitations, as evidenced by what our initial paper calls those “compensating fixes” (typically complex, imperfect and contentious) that tinker with or supplement LMP prices depending on circumstance. But can this delicate construct effectively manage a transforming grid?

Our writings pose several questions, most ignored in rebuttal, suggesting why past performance might not be indicative of future results. But on one point we seem to be talking past each other.

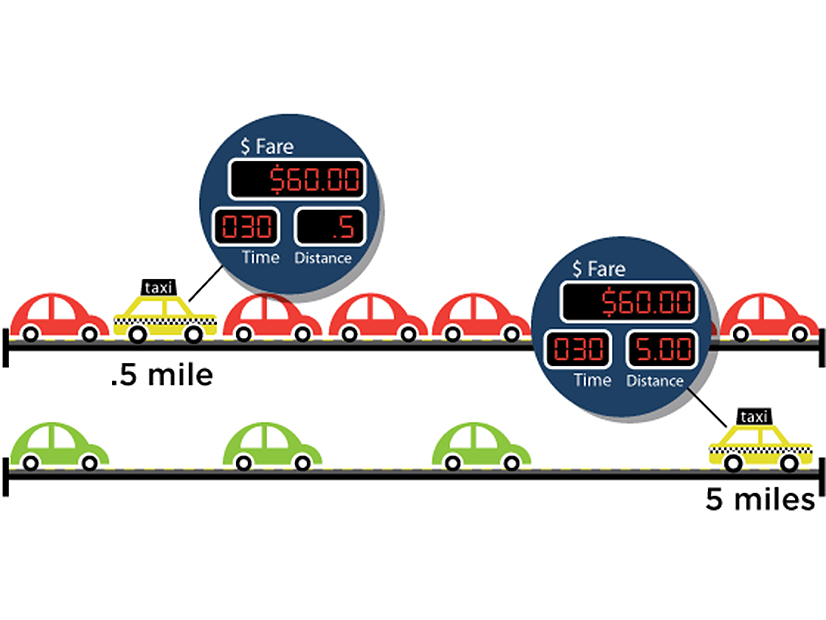

Electricity today is physically injected onto the grid by an array of generating and storage technologies having disparate operating attributes. These injections vary in character from one another (not to mention they’re poles apart from “virtual injections” offered by financial traders and demand response providers). Although these various injections each present a different profile to the system operator charged with keeping the lights on, from a market settlement perspective all are regarded as equal and paid the same. As the physical and virtual supply stack further evolves, can we continue to treat these injections as sufficiently homogenous in character to justify a single market, with a single clearing price paid to all? As we have said previously, the only thing fungible (or in the parlance of economists, “perfectly substitutable”) when it comes to electricity is the electron itself. But no buyer, including particularly the system operator, is buying mere electrons. The megawatt-hour is in fact a highly bundled product with varying operational attributes such as its constancy (or variability) over time, its ramping and load following attributes, its stability and inertia properties, its on-demand availability/dispatchability, etc. All these properties, in the right balance, are critically important to the operator in maintaining system reliability.

Some dismiss the question of megawatt-hour fungibility or substitutability as an empty formalism. And if we insisted on perfect fungibility, we’d agree with the characterization. Although treating electricity in LMP markets as fungible has always been a problematic exercise in applying “compensating fixes,” it’s been workable enough to unlock much of the benefit summarized by Hogan, Harvey and others. But make no mistake, the very basis underpinning the law of single price is a presumption of commoditization.

Here lies the problem. The debate isn’t about the merits of LMP. It’s about whether the penetration of new and transforming supply-side technologies (and demand response resources) permits us to continue to hold to a necessary predicate underlying LMP.

The following statement to RTO Insider from Professor Severin Borenstein, board member at CAISO, illustrates the communication gap:

The idea that everybody gets paid a uniform price is how commodity markets work, not just for electricity — for natural gas, for gold, for oats, for everything. There’s a market price, and people will get paid that market price because they’re selling a homogeneous good.

Similarly, Hogan and Harvey’s paper includes the oft-repeated admonition about the 1970s-era misadventure in pricing “new” and “old” oil differently. These responses miss the point. Of course, commodities should transact at a uniform price — assuming they are commodities, which is to say essentially homogenous like oil, gold, oats or anything else meeting the definition of a commodity. But equally, a market that pays the same price for different things has a problem.

Presuming we can treat equally all injected megawatt-hours regardless of the unique operational attributes associated with these injections deserves scrutiny considering changing technologies. Comments filed recently with FERC in Docket No. AD21-10 by Professor Leigh Tesfatsion offer the same, but expanded, explanation for why electricity is not like oil, gold and oats and thus why:

all attempts to justify the (day-ahead/real-time market) two-settlement system (based on LMP pricing) by means of the efficiency and optimality properties of competitive commodity spot markets (based on competitive marginal cost = marginal benefit pricing) are conceptually unsupportable.

As the legion of rulemakings pending before FERC attest, there’s no shortage of argument and opinion about the type of institutions/structures, electricity market design and transmission policy we need to facilitate grid transformation. Which is why it’s puzzling to see the intellectual architects and master builders of the current ISO structure avoid engaging on this question of electricity as a commodity. Yes, the consequences that follow from finding that a bedrock presumption no longer holds will be profound and provoke a wholesale rethinking. Here again we say read Professor Tesfatsion’s comments where she explains — ironically given how economists largely populate the field of electricity market design — that we might be ignoring the dictum of “sunk costs as sunk.” Her comments introduce the “Ptolemaic Epicycle Conundrum,” drawing on history’s long and difficult road in accepting a Copernican sun-centric solar system by thinkers (and institutions) invested in Ptolemy’s earth-centric system. This conundrum arises once we’ve all invested heavily in a certain model and layered on fix after fix as problems present, only to arrive at a sad place where “the correction of the fundamental conceptual inconsistencies in the core design principles is persistently deemed to be too costly to correct.”

So, let’s challenge the leading lights of energy economics and academia to prove that single clearing price LMP energy markets have not become “too big to fail.” Let’s examine the many ways electricity is being injected onto the grid today and the different operational attributes attendant to these injections, to ask whether a bedrock principle that directs us to pay all injections the same marginal price (varying potentially only by location) continues to hold. Answering this question is what we’re looking for from these folks — rather than a rote repetition of LMP benefits.

Former FERC commissioner Tony Clark, a senior adviser at Wilkinson Barker Knauer, has represented several vertically integrated utilities in matters regarding utility deregulation and has authored several papers critiquing retail restructuring of the electric utility industry.

Vincent Duane, the former SVP for law, compliance and external relations for PJM, is principal of Copper Monarch, which provides advice on electricity market design, governance and strategy for system operators and companies that work with them. He also is a senior adviser to Market Reform, an international consultancy.