In New England, increasing winter reliability concerns are driving questions about how long the region’s aging fleet of oil-fired power plants can, or should, remain on the system.

Power generation from oil has declined dramatically in New England since the start of the century. The oil plants that have remained on the system have run less frequently, mostly during tight winter periods when gas generators have limited access to pipelines.

Several high-profile oil units have already retired, and the large oil resources that remain face significant retirement risks.

Continued reliance on aging oil generators has real consequences: The units are among the dirtiest in the ISO-NE resource mix, both in terms of climate-warming emissions and local air pollution that can have significant health effects on nearby residents.

But ISO-NE forecasts that growing winter demand, coupled with obstacles to offshore wind development and limits to the region’s gas supply, will increase the need over the next decade for dispatchable generators with fuel storage capabilities. This may force the region to keep the units online longer than many policymakers hoped, or to invest in adding dual-fuel capabilities to existing gas-only units.

Uncertainty remains, however, around when a significant spike in winter demand will materialize. And changes in the wholesale markets — including ISO-NE’s ongoing capacity market overhaul, evolving Pay-for-Performance risks and the introduction of longer-duration reserve products — could also have significant effects on plant revenues, making it difficult to predict how long the resources will remain online.

“You see a lot of the owners of some of these oil facilities caught in between and not being able to see a clear picture as to whether the ISO, the states and other policymakers want to try to preserve those facilities or drive them into retirement,” said Dan Dolan, president of the New England Power Generators Association.

“A lot of them have been driven into retirement or been driven into a place in which they are right on the cusp of financial viability,” he said. “I, at this point, don’t have a clear line of sight as to how some of those standalone large steam units are going to function.”

Changing Economics

The New England oil fleet is old: Most of the oil-fired steam units were built in the 1970s. As cheaper, cleaner and more efficient sources of energy have come online, oil generation has declined dramatically, dropping from 18% of the total energy production in 2000 to 0.3% in 2024, according to ISO-NE.

The steepest decline occurred between 2000 and 2010. Over the past 10 years, annual oil generation has fluctuated, often following the severity of winter conditions.

But the region has continued to see retirements and a declining amount of oil capacity on the system. Between Forward Capacity Auctions 15 and 18, capacity supply obligations for generators running on distillate and residual fuel oil declined from over 4,700 MW to about 3,500 MW.

“Many of these units are at risk of retirement,” ISO-NE noted in its draft 2025 Regional System Plan. “They run infrequently, are less efficient and are nearing the end of their economic life.”

As the resources have run less frequently, they have become more reliant on capacity revenues, while low capacity clearing prices have pushed higher-priced generators out of the market, according to ISO-NE’s Internal and External Market Monitors.

Potomac Economics, ISO-NE’s External Market Monitor, wrote in its 2024 annual report that “the sustained low prices led to 760 MW of retirement bids from units with on-site fuel supplies clearing in FCA 18,” which applies to the 2027/28 capacity commitment period (CCP).

With essentially no dispatchable generating resources in the region’s interconnection queue, “it will be critical to retain a large share of the existing dispatchable generation and avoid mandating retirements of fossil fuel resources,” Potomac wrote.

ISO-NE analyses have “made it clear that we need dispatchable resources, and we need a fairly significant quantity of readily available fuel for those dispatchable resources,” said Brian Forshaw, principal at Energy Market Advisors and a longtime NEPOOL participant. He emphasized that his comments are not on behalf of any of his clients.

“The challenge is going to be how to identify what the value of retaining that capability is, and then developing some kind of a market mechanism, or a reserve product or whatever else to compensate them enough to keep them around,” he added.

ISO-NE’s Capacity Auction Reform (CAR) project, a major multiyear effort, is intended to help better align capacity procurements with actual reliability benefits.

The project proposes transitioning the RTO from a forward, annual capacity market, with auctions held three years prior to the relevant CCP, to a prompt, seasonal market, with auctions held about a month prior to each CCP, which would be divided into winter and summer seasons.

The effort also includes significant changes to how much capacity value ISO-NE assigns to different resource types. Under the current rules, the capacity market typically accredits resources based on an audited value intended to capture the maximum output they can provide. The methodology does not account for outage rates and maintenance requirements, which ISO-NE instead factors into its calculations for the installed capacity requirement.

Under the proposed CAR changes, resources would be accredited based on their marginal reliability impact value, which is intended to capture contributions to reducing energy shortfall during extreme model scenarios. Accreditation values would account for a wider range of factors, including resource outage rates, maintenance requirements, stored fuel and intermittency.

The changes could have major implications for the capacity revenues available to different resource types, though it is still early in the process to predict how the project will affect various resource classes.

“It is vitally important that the ISO-NE markets accurately signal which resources effectively support reliability and how much capacity is needed,” Potomac wrote in its annual report. “This is necessary to avoid premature retirement of fuel-secure resources, incentivize generators to acquire inventory or firm fuel arrangements, and avoid overpaying for capacity that does not support reliability.”

The changes to accreditation will likely be both positive and negative for oil generators.

Accounting for fuel storage appears likely to increase the accreditation values for oil units relative to other resources, and multiple participants involved in NEPOOL discussions also said the shift to a seasonal market may push prices up in the winter, providing an additional boost.

However, oil-fired steam resources tend to have higher outage rates and greater maintenance requirements, which will likely limit their accreditation values, regardless of their stored fuel capabilities or potential winter benefits.

The shift to a prompt market would also allow resources to submit retirement notifications much closer to each CCP; it would reduce this notification deadline from about four years to about one. This would enable participants to make retirement decisions based on more up-to-date information about the conditions of the market and their resources.

“There’s so many variables and moving pieces to that design — it’s going to be hard to get a clear picture until we see more about how all those pieces fit together,” NEPGA’s Dolan said.

Some stakeholders also expect future capacity prices to reflect a perceived increase in PFP risk. Capacity scarcity events trigger the PFP rules, which penalize resources with capacity obligations that fail to perform and reward resources that deliver more than their obligations.

Some oil-fired generators have racked up significant penalties during PFP events in recent years. The resources generally require significant advance notice to ramp up and come online, making them ill-suited to perform during unexpected scarcity periods.

“I think it’s fair to assume that the higher Pay-for-Performance risk that people are now starting to perceive will work its way into the supply offers that will get submitted into the market,” Forshaw said, adding that this will likely put “some upward pressure on prices.”

New Mechanisms

Taking all factors into account, “the expectation is: Some of the older resources that do maintain significant inventories of residual oil are going to face challenges going into [the 2028/29] time frame and may consider submitting deactivation notices one year prior to the start of the delivery period,” Forshaw said.

With looming retirement risks and ISO-NE’s forecast that winter reliability risks will rise in the mid-2030s, it is important to begin discussions on potential solutions and new mechanisms, he said.

In a statement, ISO-NE noted it is evaluating “the potential addition of a longer response reserve product, such as a 60- or 90-minute reserve, to help manage uncertainties caused by the increasing variability of renewable generation and real-time system demand,” which may provide additional opportunities for oil resources.

The RTO also recently established a new Regional Energy Shortfall Threshold (REST), which is intended to define an acceptable amount of shortfall risk in the region. It plans to use the threshold to evaluate risks prior to each winter and summer season, as well as in long-term assessments. (See ISO-NE Proceeding with Shortfall Threshold After Positive Feedback.)

It has yet to determine how it would select and develop solutions to mitigate risk if the threshold is violated.

Data from long-term assessments “will guide evaluation of whether the possibility of exceeding the REST in those time frames requires development of regional solutions to mitigate modeled risks and, if so, when to begin to develop solutions; these efforts would be signaled in future annual work plans,” ISO-NE wrote in a statement.

The RTO has yet to deploy the threshold in long-term, forward-looking studies. ISO-NE’s probabilistic modeling for the upcoming winter indicates the region is well short of the risk threshold. (See ISO-NE Forecasts Minimal Shortfall Risk for Upcoming Winter.)

Forshaw emphasized the importance of establishing the process for addressing REST violations well before they occur, noting that major market reform frequently is a multiyear process.

If studies show high risks of energy shortfall because of a lack of fuel, it could make sense to procure fuel, or another type of energy, that would “only be used when we’re facing load shedding, rather than in the normal course of dispatch,” he said.

Interest in Dual Fuel

Regardless of potential new mechanisms or the specifics of the accreditation changes, some of the region’s aging oil generators may be nearing the end of their useful life. Resource owners that are willing to keep units online, waiting for a spike in capacity prices, may be unwilling to make large capital investments in the case of major mechanical failures.

This long-term outlook, coupled with the region’s winter gas constraints, has driven some increased interest in adding dual-fuel capabilities to existing gas plants, enabling them to burn oil during winter periods when gas prices spike or the units are unable to access gas.

“Given the slowdown on offshore wind and the other changes at the federal level that have really slowed down the scale and the pace of other clean energy entry, there’s been a lot of interest from state policymakers, ISO New England and others about exploring what capabilities exist out there for adding more dual fuel to make up this megawatt-hour gap that may be in front of us,” Dolan said.

Potomac wrote in its report that adding on-site fuel storage to gas-fired resources is “likely the lowest-cost strategy for addressing winter reliability concerns in the near-term in light of the issues with offshore wind development.”

However, there is uncertainty as to whether the states would allow the facility changes, or if the market would support the investments, Dolan said. He added that dual-fuel investments likely would require “over a decade of payback … and years of development to put it into place.”

He noted that the tensions and contradictions between state and federal policy have created significant development challenges for a broad range of resource types.

“It’s a really tricky environment, and I don’t have a clear answer of what to do about that,” Dolan said.

Clean Energy Solutions and Environmental Impacts

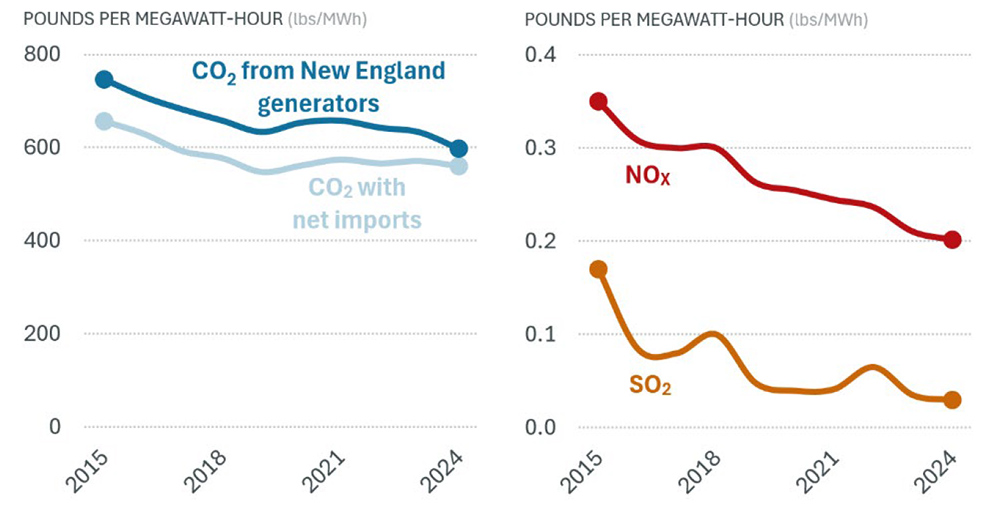

The decline in oil generation, and the replacement of inefficient oil and coal units with cleaner gas plants and renewable energy, has coincided with significant reductions in emissions from nitrogen oxides and sulfur dioxide, according to ISO-NE’s 2024 emissions report.

The RTO notes that between 2015 and 2024, sulfur dioxide emissions declined by 82% and emissions from nitrogen oxides dropped by 42%. This compares to a 15% decline in carbon dioxide emissions.

Oil-firing power plants “are among the highest-polluting resources that we have,” said Joe LaRusso, manager of the clean grid program at the Acadia Center. “Many of them are located in communities that are overburdened with air pollution as it is.”

Nitrogen oxides and sulfur dioxide, along with fine particulate matter, are air pollutants associated with a range of heart and lung issues, child asthma, cancer, autoimmune diseases and neurological harm, according to the American Lung Association.

In Massachusetts, these pollutants were responsible for 2,780 excess deaths in 2019, according to Boston College researchers.

While it is difficult to attribute deaths to specific generation types or plants, the study notes that stationary sources, which include power plants, industrial facilities, and heating and cooking, were responsible for about 30% of fine particulate pollution in the state.

Concerns about health effects have motivated grassroots movements to block the development of new peaking plants. In Peabody, Mass., residents fought bitterly and, ultimately, unsuccessfully to stop the construction of a dual-fuel peaker, which came online in 2024.

Any efforts to add oil capacity in the region, or to implement market mechanisms propping up these units, would likely be met with opposition from environmental groups.

LaRusso said he is optimistic that three large projects nearing completion — Revolution Wind, Vineyard Wind and the New England Clean Energy Connect (NECEC) transmission line — will reduce the need for oil peakers, potentially pushing additional units into retirement.

NECEC is intended to supply the region with a consistent source of baseload power, while offshore wind performs best in the winter, when oil units run the most. Clean energy and consumer advocates also hope that aggressive demand-side initiatives will cause load to grow at a slower pace than is projected by ISO-NE.

In the long term, LaRusso said the resumption of offshore wind development in New England, the start of offshore wind development in Nova Scotia and increased bilateral power exchanges with Quebec could help the region meet growing winter demands while eliminating most of the remaining need for oil-fired generation.

“It seems that oil is going to follow the same path as coal, unless the demand curve starts rising so fast that batteries can’t keep up,” he said. “There are so many factors in play, but none of it appears to provide a rosy picture for an oil-firing plant.”