By Chris O’Malley and Rich Heidorn Jr.

INDIANAPOLIS — MISO will release the results of its latest resource adequacy survey later this month, after a survey last year caused alarm, with forecasts of capacity shortages in three zones in MISO North and Central.

How bad will the new numbers be? And how can MISO increase its reserve margins in the future? Those were among the topics that dominated discussion at Infocast’s MISO Market Summit last week.

“We do not have a capacity shortage,” Lin Franks, Indianapolis Power & Light’s senior strategist for RTO, FERC and compliance initiatives, said flatly. “The message has been ridiculously presented to the world as if the sky is falling. The sky is not falling. It’s been very difficult with [the Environmental Protection Agency] disrupting all our planning processes, but we are rallying. We are solving it. We have an obligation to serve load and damn it, we’re going to.”

Franks found some support from Kathleen Spees, a principal of The Brattle Group. “There’s more [capacity] that gets offered than comes out in these surveys. So I’m not particularly worried that we’re really going to have a shortage.”

Snapshot in Time

Franks said the survey data, which is collected by the Organization of MISO States, makes the situation look worse than it is.

Utilities are asked, for example, about the certainty of their plans for new generation. “[You] are never certain at all until you get your certificate of public convenience and need. So it’s not a graduated certainty. It is or it isn’t, period,” she said. “What you’re seeing is a snapshot in time. It doesn’t mean that there won’t be a solution [when the capacity is needed].”

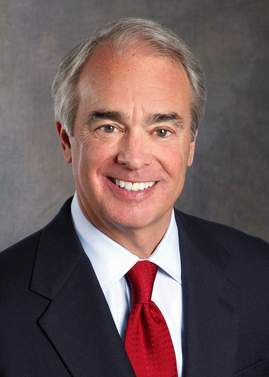

Joseph Gardner, MISO’s vice president for forward markets and operations services, said the RTO will change how it presents the survey data in the new report. “So hopefully it will address some of those things,” he said.

There is no question, however, that MISO, which has enjoyed reserve margins exceeding 20% in the past, is facing a much tighter future.

Calls on Interruptible Loads to Increase

Gardner noted that it’s been nine years since MISO last deployed its load-modifying resources — currently about 6 GW of behind-the-meter generation and 4 GW of interruptible loads.

“We’re going to start having to use that quite often. I don’t expect we’ll have to use it very often this year, but we do expect to use it very often starting next year,” he said. “How often is hard to tell. It depends on what kind of a summer we have. If we have a summer like we did three years ago: not much. If we have a summer like we did two years ago: a lot — upwards of two dozen times of more.”

That could result in departures from the program, Gardner and others said.

“Essentially those interruptible customers start to look like a peaking generator,” said Chris Plante, director of resource planning and policy for Wisconsin Public Service. “Those customers … are not accustomed to regular interruptions. Our thought is that as they start to experience those interruptions, they may actually decide to leave the interruptible program and become firm load, which of course makes the situation even more tight.”

David Sapper, director of midcontinent regulatory affairs for Customized Energy Solutions, said MISO officials’ recent suggestion that they are considering testing the response of interruptible loads may also contribute to defections.

Challenges to Adding Generation

Losses of interruptible loads would make the construction of new generation even more crucial. But that won’t be easy, Plante said, because of “friction” in MISO’s interconnection process.

“You have to get into the MISO interconnection queue early enough so that you get your study results done and you get the transmission issues identified. Usually that time frame is so long that I don’t even have a good idea yet on whether I’m going to build a one-on-one combined-cycle or a two-on-one. If it’s a one-on-one, is it 400 MW or is it 450 MW? That might not seem like a big deal, but to MISO’s interconnection process it’s a big deal. You can’t go in with 400 and later say, ‘Well it’s really 450.’ You have to get out of the queue and get back in with 450.”

Plante also criticized MISO’s modeling of wind power at 100% of nameplate capacity during off-peak hours. “When my combined-cycle is modeled at 100% and the wind’s modeled at 100%, there’s all kinds of constraints. And those constraints show up in my interconnection agreement as issues that I need to resolve before I can count that generator as capacity. Depending on the lead time of those constraints, I might have to wait for 10 years [for a major transmission project] before I can get the capacity value out of that combined-cycle when in reality … we believe that off-peak wind probably won’t be at 100% and the constraints that MISO identifies might not ever show up.”

No Rescue from IPPs

Don’t expect to see independent power producers riding in like the cavalry to build new generation.

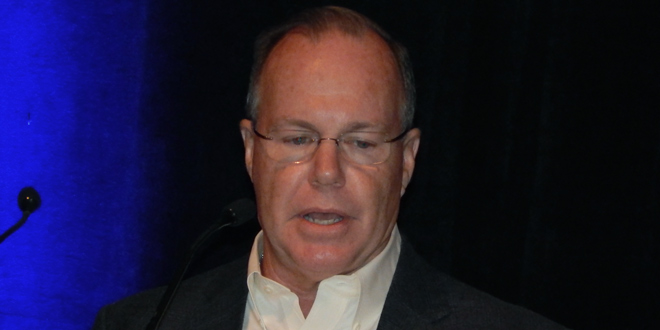

Brett Kruse, vice president of market design at Calpine, said his company won’t build in MISO without a contract because all but two of its states are dominated by vertically integrated utilities and its voluntary capacity market provides too little revenue.

“The contract has to be 10 or 20 years depending on how much you can frontload it … where you basically have to stick all the value of your plant into that contract, because once you get out and you’re a merchant plant in a construct like [MISO], you have very little value other than what you’re seeing the IPPs in Michigan do: Either you build a line to get into PJM like [Tenaska Capital Management’s Covert, Mich., plant] did or you sell to the utilities.”

As the biggest natural gas buyer in the U.S. and one of the biggest operators and builders of gas-fired generation, “I can build … a gas-fired plant cheaper than anybody else in America. … We’re very confident we can run circles around any utility self-build in America.”

But he added, “If I went to my board and said I wanted to invest $500 million into building a [merchant] plant in MISO, they’d laugh me out of the room — and then fire me.”

Until recently, MISO’s ample reserve margins have meant there hasn’t been much need for merchant entry, said Brattle’s Spees.

Capacity Prices Too Low?

But, she said, “That’s not going to last forever. The only way it can last forever is if the regulated states overbuild into perpetuity by a sufficient margin that they can meet the resource adequacy needs of their neighbors” in Illinois and Michigan, the two MISO states with retail competition.

Spees said she sees promise in the concept of setting up a PJM-like forward capacity market for the states with retail choice.

Marka Shaw, a director of wholesale market development for Exelon, also criticized MISO’s structure, saying it is not only unable to attract new entry but also provides insufficient revenue to cover expenses for existing baseload generation, such as Exelon’s Illinois nuclear fleet.

Kruse and others agreed that MISO’s capacity prices are too low, with some noting that the $150/MW-day price seen in Illinois Zone 4 in the most recent auction — which sparked complaint to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission last week — is less than two-thirds of the $247/MW-day cost of new entry in the zone. (See Public Citizen to FERC: Investigate Dynegy Role in MISO Capacity Price Jump.)

Gas vs. Nuclear

But Kruse’s Calpine colleague, Joe Kerecman, jumped into the discussion from the audience to criticize what he called Exelon’s request for “out-of-market subsidies.” Exelon has been lobbying for the Illinois legislature for a bill that would charge Illinois electricity users a fee to ensure continued operation of three nuclear generators that the company says are unprofitable. On Monday, Exelon acknowledged that the legislation would not pass during the current legislative session.

“These plants are also getting old,” Kerecman said, accusing Exelon of abandoning its support for competitive markets. “There’s a fallacy that they won’t get replaced.”

“Clinton [one of the generators Exelon says is losing money] is one of our newest plants,” Shaw shot back.

Shaw found support in Spees, who said the relief nuclear operators are seeking is to address the unpriced cost of carbon emitted by coal and natural gas plants. “That’s a market failure,” she said.