WASHINGTON — Every energy industry conference has its own particular buzz ― what attendees are talking about, not only on stage but in the side conversations between sessions, at lunches and receptions. At Deploy23, it was all about two questions: How can we do more and how can we do it faster?

Coming off the Earth’s hottest summer on record, the two-day conference Sept. 26 and 27 zeroed in on the public-private partnerships that will be needed to optimize the impact of every single penny of the billions in clean energy funding in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

More than one speaker said that building and maintaining a sense of urgency is critical. A recent report from the International Energy Agency calls for a tripling of renewable energy and doubling of energy efficiency improvements by 2030, along with a major ramp-up in electric vehicle (EV) and heat pump sales, to limit climate change to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

The IIJA and IRA funds, while unprecedented, are insufficient, said Jonah Wagner, chief strategist for the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office (LPO), which cosponsored the event with the Cleantech Leaders Climate Forum.

“We have to execute,” Wagner said. “And we have to execute in a way that captures the complexity and the implications of government engaging in competitive markets and supply chains, labor, workforce and community engagement, all of it. … We have to develop a shared understanding between the public sector and the private sector and then a whole broader ecosystem around how we’re going to get there.”

In his opening remarks, White House Senior Advisor John Podesta called for private sector “ownership” on the three key issues creating a drag on clean energy deployment — permitting, supply chains and workforce.

“We need you to keep voicing support for broader permitting reform at the federal, state and local level, and we need you to take responsibility for community engagement for your own projects,” Podesta said. “Get in early, engage local leaders early; and often we can address concerns that are raised at the community level, find ways to mitigate challenges on the ground and get these projects built.”

Breaking China’s dominance over clean energy supply chains is a more complex issue. While Podesta and other administration officials typically boast about the $150 billion in private sector investments in clean energy supply chains announced since the passage of the IRA, that early money has been concentrated in certain low-hanging opportunities – electric vehicles, batteries and solar panels.

But companies need to “get creative … to invest in projects up and down the supply chain, innovate in pursuit of a circular economy,” he said.

Podesta stayed on message on workforce development, calling for good wages and benefits, apprenticeship programs and opportunities for unionization. But, according to Undersecretary for Infrastructure David Crane, the immediate need at the Department of Energy is for professionals who know the nuts and bolts of project development.

“We’re looking at having 200 to 300 projects in active development by next year,” Crane said. “The skilled workforce that we need now, and where we’re entirely dependent on the private sector, is on structuring these transactions. We need the lawyers, the financiers, the tax advisors. We need the developers that can structure these transactions.”

Communication, Collaboration, Coordination

Getting projects built often means people who disagree on some issues have to find ways to work together, said Mitch Landrieu, White House infrastructure coordinator.

Recalling his own experiences as mayor of New Orleans, rebuilding the city in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Landrieu said creating a “virtuous cycle of success” for infrastructure development required alignment of federal, state and local government, along with the private, nonprofit and community sectors.

“It’s about setting up what I call a mousetrap, the scaffolding of government where not only are we trying to do a thing, but how we’re trying to do it is coordinated — so, communication, collaboration, coordination,” Landrieu said. “If, for example, we get in a fight with a red state governor or … a blue state mayor, or the mayor and the governor are not on the same page, it will slow down our ability to move stuff to the ground because government is kind of an essential part of the spine in partnership with the private sector.”

Landrieu also argued for a broad definition of “infrastructure,” encompassing bridges, broadband and childcare.

“If you sit in a room of all women ― CEO all the way down to the person who’s cleaning the floor ― and you ask them what’s the most important thing that they need to actually show up and do that work, they’ll say childcare ― 100%,” he said. “So, my brain goes with ― childcare is infrastructure ― because if you can’t have people that do it, you can’t build stuff.”

Whether for clean energy or childcare, the foundation of public and private partnerships, he said, is “a commitment and then a willingness for everybody to show up and find common ground by pushing away the extremes and staying focused” on shared goals.

‘Getting Scrappy’

A “fireside chat” on electric cars and buses as grid assets explored both the opportunities that managed charging and virtual power plants (VPPs) present and the challenges of working with utilities to get charging stations and manufacturing plants interconnected.

Light-duty electric vehicles (EVs) typically use about 12 kWh of power a day, but when fully charged, their batteries have a much larger capacity, said Patrick Bean, director of infrastructure policy and business development at Tesla.

“So, there’s a lot of opportunity and diversity in [when people] charge … and their cars are typically sitting either 23 hours a day, 22 hours a day,” he said. “It’s a great opportunity to optimize that charging behavior for the best off-peak time, low-carbon times.”

Tesla has been piloting virtual power plants that aggregate capacity from its residential Powerwall energy storage units, and it recently launched another pilot in Texas offering Tesla EV owners a flat monthly rate of $25 for unlimited charging scheduled by the company for off-peak hours between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m., he said.

Customers can enroll via a cell phone app, “so it’s something we’re trying to make very digestible, very easy for customers to understand because if it gets too complex, they’re going to say, ‘This is too much,’” Bean said.

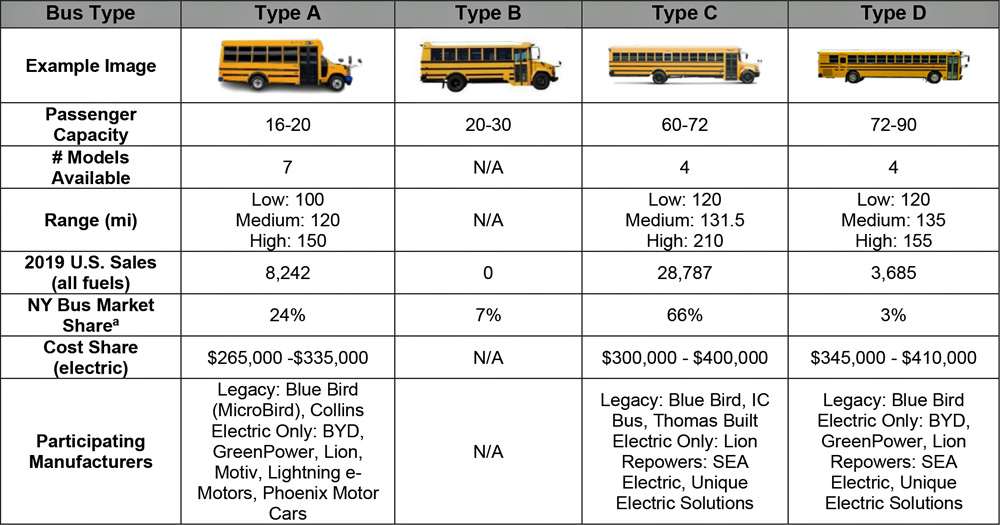

California–based Zum is offering school districts electric transportation — buses, vans and passenger vehicles — as a service, with apps so parents can track when their kids will be home from school.

School buses are “the largest mass transit system in the U.S.,” getting 27 million students to and from school each day, said founder and CEO Ritu Narayan, and their set schedules and evening, weekend and summer availability make them perfect for electrification and managed charging applications, like VPPs.

But, Narayan said, “the challenges are various. … The first step to that is optimizing the entire system and application, and second is establishing of the entire ecosystem, right from the manufacturers to the charging infrastructure to establish the aggregation around it” so Zum can be a one-stop shop for school districts seeking to electrify fleets.

On the interconnection side, working with utilities has become a critical part of Bean’s work at Tesla, as the company looks to expand its factories and charging networks and runs into the multiyear timeframes utilities often set for distribution system upgrades and interconnection.

As Tesla looks toward exponential growth in EV sales, he said, it can be “really hard to build utility infrastructure at an exponential rate, and I hope we can try it … because there are a lot of no-regrets investments [in] infrastructure that we know are going to be necessary. …

“There’s a lot that can be done just from a process perspective and better coordination … and just getting scrappy and coming up with new ideas to get infrastructure built,” he said, pointing to a recent example in which Tesla was able to get a new energy storage factory interconnected in 12 months.

The challenge, Bean said, is getting utilities and industry trade groups to “realize and understand that what has worked in the past is not going to work going forward. So, we need to change the processes together. …

“This is not a distributed grid versus a central grid,” he said. “Seven or eight years ago, there were concerns about a ‘utility death spiral.’ Now we’re just trying to figure out how can we support double-digit load growth, and that’s going to take a lot of coordination between the central grid and the distributed grid.”

Getting to Scale

JB Straubel, founder and CEO of Redwood Materials, knows all about scaling a business. The former cofounder and chief technology officer at Tesla, says the U.S. EV and battery supply chains have a long way to go, which is part of why he started Redwood, which recycles lithium-ion batteries to produce the critical minerals needed for EV production.

Tesla received a $465 million loan from the LPO in 2010 and finished paying it back in full by May 2013, according to the agency website. Earlier this year, Redwood received a conditional commitment from the LPO for a $2 billion loan to help it expand its plant in Nevada.

But, Straubel said during an on-stage conversation with LPO Director Jigar Shah, “I think it’s underappreciated, especially by some of the … early investment community and a lot of startups, how difficult it is to achieve scale. It’s a whole new category of problems.

“Supply chains break, geopolitics come into it. [Challenges] rise to a whole new magnitude in terms of what you’re doing when you do 100 times as much of it,” Straubel said. “It requires a different set of engineering skills and a different set of business skills.”

With a series of recent announcements on new EV and battery manufacturing facilities across the U.S., “it’s sort of tempting to feel like we’re almost there,” he said.

“But we really looked at the objective numbers on where we are on supply chain onshoring or even just supply chain geopolitical security … it’s not very far along,” he said. “Building out that robust supply chain, making sure we are being strategic ahead of time about where we invest, to kind of [look] at where the puck is going — it is just going to be critical.”

While Redwood is producing lithium and nickel, Straubel said, “until there is an entire EV supply chain, there’s nothing to do with it. … If I had a pile of lithium sitting here on the stage and went to go sell it, where do we think all the buyers would be?”