WASHINGTON ― For the U.S. — and the world — to cut greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050, “we need in the next 27 years to transform the global economy on a size and scale that’s never occurred before in human history. That’s your charge,” White House Senior Adviser John Podesta told an audience of several hundred clean tech innovators and entrepreneurs at Deploy23 on Tuesday.

Podesta was one of a stream of administration officials and industry leaders speaking at the two-day event, aimed at fostering the deep public-private partnerships, innovation and private investment needed to scale clean energy technologies and curb the impacts of climate change.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) have provided unprecedented billions to incentivize clean energy investment, said Jigar Shah, director of the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office (LPO), which is dispensing a good chunk of those dollars in the form of loans to clean tech companies.

The LPO co-sponsored the event — officially Demonstrate Deploy Decarbonize 2023 — with the nonprofit Cleantech Leaders Climate Forum.

“We have an extraordinary group of companies who really are showing ambition” to fully use the opportunities in the two laws,” Shah said in a Wednesday interview with NetZero Insider. The problem is that “the United States is not known for the quality of its public-private partnerships.”

“The U.S. is sort of like — ‘we just signed a one-time contract, and we hope we thought of everything because revisiting the partnership every year is not our jam,’” he said. “We need to learn how to do things better and smarter.”

Critical to those better relations is the effort of Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm in recruiting a cadre of energy industry leaders — like Shah, a serial entrepreneur and investor before heading up the LPO — who have cultivated a more business-friendly vibe at the agency.

“The private sector has heard that DOE wants to hear their opinions and is willing to be responsive to what they have to say,” Shah said. One example: The event featured several “Deploy Dialog” sessions, involving industry roundtables that were by invitation only and closed to reporters.

In a prerecorded message, Granholm stressed the central role of industry-government partnerships. The U.S. has a “not-so-secret weapon, which is a government that doesn’t think it alone has all the answers, and business that prides itself on problem-solving,” she said.

“It’s about more than just [research and development],” she added. “We are harnessing the potential of American industrial strategy — clear-eyed cooperation instead of blind heavy-handedness.”

At the same time, those partnerships will need to be built on “developing and embedding a culture of net-zero innovation in the marketplace,” said Anne Slaughter Andrew, chair of Cleantech Leaders Climate Forum, in a Wednesday morning keynote.

“Incrementalism doesn’t work; we have to go big. And what does this mean?” Andrew asked. “It’s not just encouraging the disruptive, new clean-tech companies and startup entrepreneurs. Legacy companies and institutions also must adjust, repurpose and realign their mission and their goals to coexist in a vibrant and integrated culture of innovation that is aimed at net-zero greenhouse gas emissions.”

“Change is no longer a decadeslong process. In fact, with the advent of AI-inspired research, change will happen continuously and faster than ever before,” she said. “Net-zero innovation has to become a core competency for every business, from startups to legacy corporations.”

Getting to ‘Fast Follow’

The figures have become a standard part of almost any energy-related presentation by a DOE or White House official. The various incentives and tax credits in the IRA and IIJA — more than $400 billion in total — mean the American clean-tech market is “wielding an economic bazooka,” Granholm said.

In the 13 months since President Joe Biden signed the IRA, about $150 billion in new private investments in clean energy manufacturing has been announced in red and blue states across the country, Podesta said.

“On top of that, utilities have announced more than $120 billion for clean energy generation, and over the last year, 4% of our total investment in structures, equipment and durable consumer goods was in clean energy,” he said. “That’s more than double what it was four years ago.”

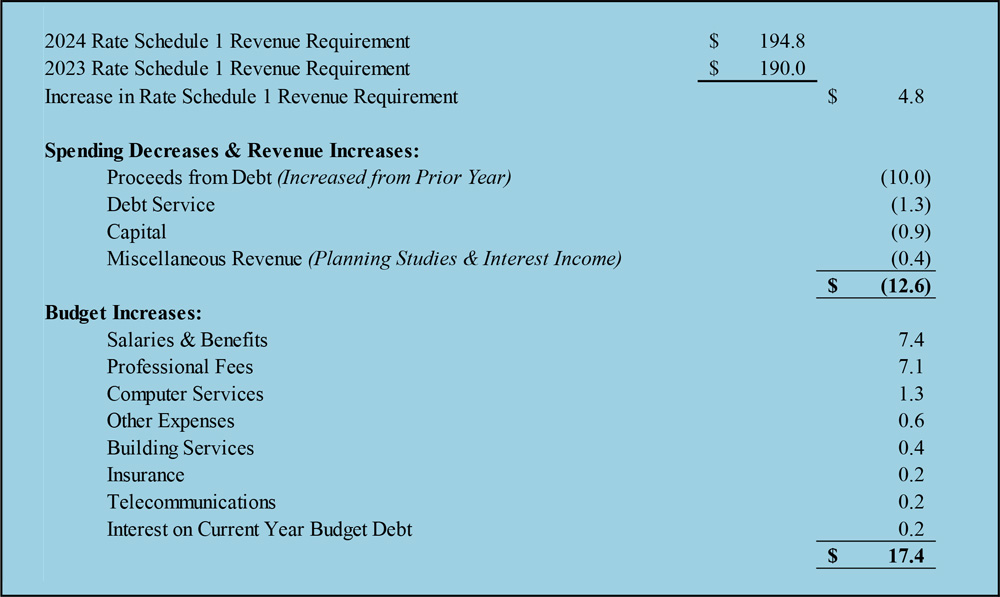

But according to Jonah Wagner, the LPO’s chief strategist, the country still is lagging behind the $300 billion per year in private investment needed to meet Biden’s climate goals ― a 100% decarbonized grid by 2035 and net zero economywide by 2050.

The LPO itself has applications in for $143.9 billion in loans, 90% of which are for “mature technologies,” such as electric vehicles, batteries, solar and wind, Wagner said.

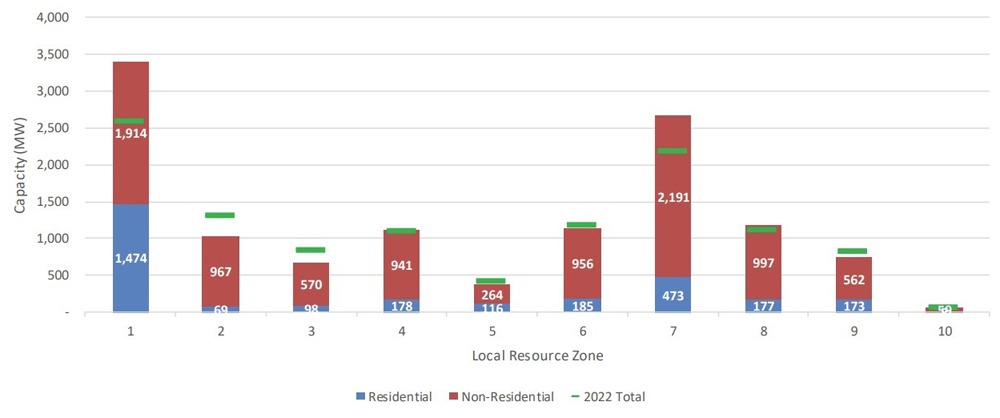

On Thursday, for example, the office announced it had finalized a $3 billion partial loan guarantee to Sunnova Energy Corp. for a project that “will make distributed energy resources (DERs), including rooftop solar, battery storage and virtual power plant (VPP)-ready, consumer-facing software, available to more American homeowners.” The loan is the U.S. government’s largest single investment in solar, and its first in virtual power plants, the announcement said.

But the projects LPO has in the pipeline are “weighted about 60-40 towards the emerging technologies that are proven but have not yet achieved commercial development,” Wagner said.

“We need all of these technologies to scale … through 2030 if we’re going to hit and achieve our goals, and … we need the private sector to lead,” Wagner said. “We need all of us in this room to work together to figure out how we’re going to get there.”

DOE officials highlighted the agency’s Pathways to Commercial Liftoff series, which includes reports on the barriers to scale and commercialization, and possible solutions, for emerging technologies such as advanced nuclear, green hydrogen and carbon capture.

DOE Under Secretary for Infrastructure David Crane, another of Granholm’s industry recruits, said the reports are intended “to get the private sector comfortable with … these maturing technologies by putting the information that we get out into the public domain. … The difference between immature and mature technologies is often access to information.”

The ultimate goal is replicability, Crane said. “We need to create a fast-following wave of private sector investment in these technology areas that don’t depend on federal money, and that needs to be in the trillion-dollar plus [range]. So, triggering that fast-following wave is important … in terms of innovators; that’s where the financiers come in and that’s where the dialog between us is important,” he said.

Crane, Podesta and Shah all talked about the critical role community engagement and community benefit plans will play in getting emerging technologies through the local permitting and approvals for projects essential for commercial scale.

Early engagement backed up by solid economic and community benefits are “how you create durable support for these kinds of policies, so that it doesn’t matter what administration is in place,” Shah said. “The American people continue to believe that we can actually manufacture here, that we can innovate here, that we can export to other countries.”

The ultimate motivation for DOE’s push for public-private partnerships is a shared sense of urgency, Crane said.

“This might be our last great opportunity to bend the curve on climate change while providing safe, affordable and reliable energy to the American public,” he told an auditorium full of industry executives. “So, I’m asking you, whatever you’ve got, I’ve got to have it now.”