President Joe Biden wants 50% of all new car sales across the U.S. to be zero-emission vehicles by 2030, and according to a new report from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), meeting that goal could require a nationwide network of 28 million charging ports, the majority of which would be located at single family homes.

Intended as a basic needs assessment, the 2030 National Charging Network report estimates 26.8 million Level 1 and Level 2 (L2) charging ports will be needed at single family homes, multifamily dwellings and workplaces. Another one million L2s should be installed in publicly accessible locations near homes and workplaces ― for example, in urban neighborhoods and at retail outlets ― while 182,000 DC fast chargers would be located along highway corridors and in rural or remote communities.

“In contrast to gas stations, which typically require dedicated stops to public locations, the [plug-in EV] charging network has the potential to provide charging in locations that do not require an additional trip or stop. Charging at locations with long dwell times (at/near home, work or other destinations) has the potential to provide drivers with more convenient experiences,” the report says.

But DC fast chargers are critical for “long-distance travel and ride-hailing, and to make electric vehicle ownership attainable for those without reliable access [to] charging while at home or at work,” a demographic that could represent about 3 million vehicles by 2030, the report says.

The report projects those chargers could be powering anywhere between 30 million and 42 million EVs but bases its topline calculations on a “mid-adoption scenario” of 33 million EVs on the road by 2030. The price tag has an even wider range, between $53 billion and $127 billion, due to “variable and evolving equipment and installation costs observed within the industry across charging networks, locations and site designs,” the report says.

The big numbers in NREL’s needs assessment are daunting in the face of current figures from the Department of Energy, counting about 140,500 publicly accessible charging ports spread across 54,200 locations. State and local policies could play a major role in bridging that gap, but according to a second report from the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE), planning for EV adoption and charging in many states is moving at a crawl.

The 2023 State Transportation Electrification Scorecard ranks states across a range of EV policies — from planning to consumer incentives to utility policies and grid optimization. The highest possible score is 100, but ACEEE found 17 states with so few points, they weren’t included on the scorecard. Only nine states scored more than 50.

California (88 points) took the No. 1 spot, followed by New York (62) and Colorado (61). Massachusetts, Vermont, Washington, New Jersey, the District of Columbia and Oregon all scored in the 50s.

“We are seeing incremental progress, not transformational progress. States will have to move far more aggressively to do their part to enable the electric vehicle transition that the climate crisis demands,” said Peter Huether, senior research associate at ACEEE and lead author of the report. “Auto manufacturers are expanding their EV options and consumers are increasingly choosing them, but supportive state policies are needed to ensure that the electric grid is ready and that all households and businesses, including those in underserved communities, can use EVs and have adequate access to charging.”

The challenges ahead for a build-out of charging infrastructure include a lack of regulations that require both utility planning and the adoption of EV-ready building codes, according to the ACEEE report. Less than half of the states are requiring utilities to plan for the installation of chargers, both private and public, though many utilities are planning for EV charging, Huether said.

Even fewer states ― 12 in all ― have EV-ready building codes, for example, mandating that new construction either be wired for or include charging stations. Having the wiring for charging built in will be especially important for multifamily housing, where residents may be wholly dependent on public chargers.

A Patchwork of State Policies

The transportation sector accounts for the largest portion of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions ― 28% versus 25% for the electric power industry, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Biden has made transportation electrification a cornerstone of his drive to reduce the country’s GHG emissions 50% to 52% by 2030, in line with his commitment under the Paris climate accords. Major automakers have followed suit with commitments to sell increasing numbers of electric vehicles within the next 10-20 years.

General Motors has pledged to go all electric by 2035, while Ford has said it is targeting 50% electric vehicle sales by 2030.

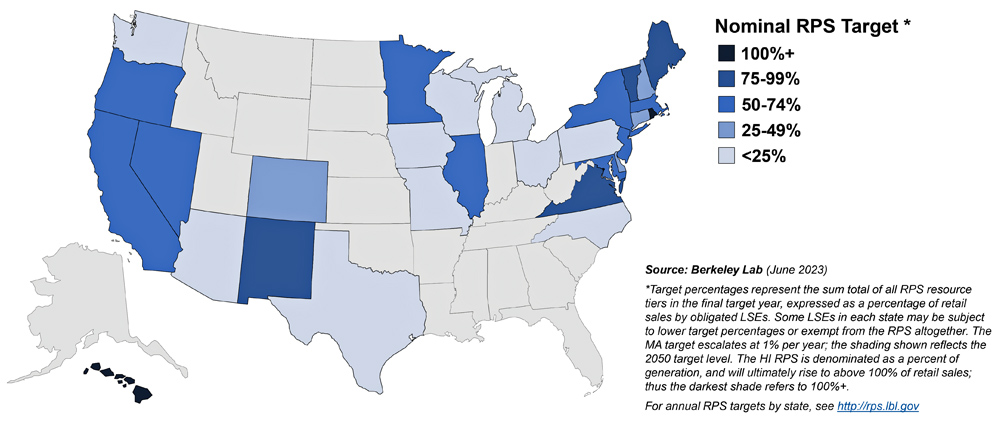

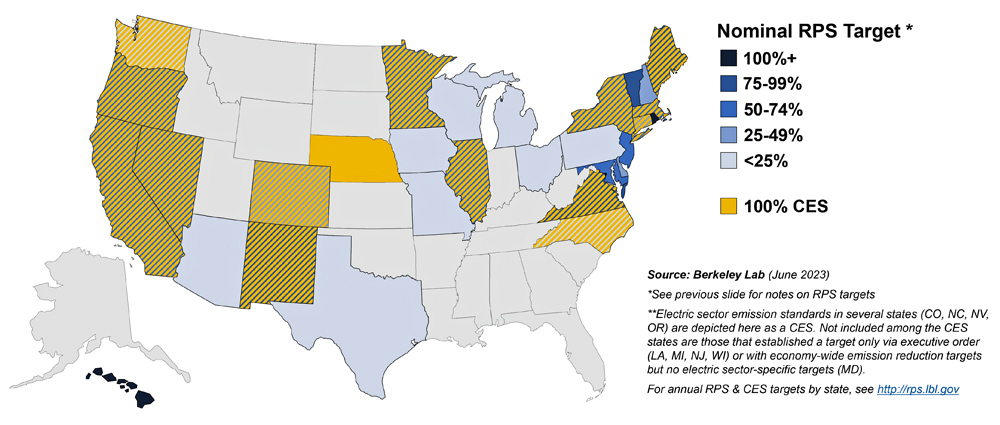

California also has set the pace with its Advanced Clean Cars II rule, requiring all new passenger cars, trucks and SUVs sold in the state to be electric or zero-emission by 2035. Five states — Massachusetts, New York, Oregon, Vermont and Washington — also have adopted the rule.

But outside these states — all in ACEEE’s top nine — what both reports show is a patchwork of EV adoption and charger installation across the country, with a range of variables either accelerating or slowing down electrification of the transportation sector.

For example, the NREL report calls for 182,000 DC fast chargers on highways versus the 500,000 goal Biden set for the National Electric Vehicle Initiative (NEVI) program funded with $5 billion from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

Initially, the proposed guidelines for NEVI called for all chargers funded by the program to be at least 150-kW DC fast chargers, but the final guidelines issued in March allow a mix of fast and L2 chargers, reflecting trends in EV adoption and charger use.

Eric Wood, a senior EV charging infrastructure researcher at NREL, said the charging network study “exhaustively considers how people in the U.S. use light-duty cars to travel, what their energy needs are for that travel, and how we can meet those needs, given projected EV adoption rates.”

“Detailed transportation data … enabled the team to answer questions like: How will EV adoption in neighboring states impact the demand for public fast charging along highway corridors in my area? And how might that out-of-state demand compare to charging needs from residents in my area?” Wood said in a blog post on the report.

The report itself points out that while prospective EV buyers prioritize the availability of fast chargers, “consumer preferences tend to shift after an [EV] purchase is made and lived experience with charging is accumulated. Home charging has been shown to be the preference of many [EV] owners due to its cost and convenience.

“This dichotomy suggests that reliable fast charging is key to consumer confidence, but also that a successful charging ecosystem will provide the right balance of fast charging and convenient destination charging in the appropriate locations,” the report says.

Balancing of the supply of chargers with the deployment of EVs is another critical issue that must be worked out on the local level, the report says. “Actual charging infrastructure will likely be necessary before demand for charging materializes.” Having chargers on the road is, again, essential for building consumer confidence, but “infrastructure investment should be careful not to lead vehicle deployment to the point of creating prolonged periods of poor utilization, thereby jeopardizing the financial viability of infrastructure operators,” the report says.

Oklahoma Most Improved

The uneven distribution of EVs and EV chargers will likely continue, according to the NREL report. Looking ahead to 2030, the report estimates that California will have more than 7.3 million EVs on the road and 262,100 publicly accessible L2 chargers versus Wyoming, which will have 50,000 EVs and 2,100 public chargers.

ACEEE’s Huether said he hopes the combination of industry commitments and federal action – like NEVI and the EV tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act – will spur more states to start planning.

Certainly, population numbers and demographics are central factors for some states, but “there are states that are just not taking transportation electrification seriously,” he said in an interview with NetZero Insider. “Maybe that’s because they don’t see it as much in their state, or they don’t recognize the benefits as much.”

Although many of the low-scoring states have Republican-dominated governments, Huether said the split between high- and low-scoring states on the scorecard is not purely political. “Oklahoma was our most-improved state in terms of rank,” he said, moving up eight spots. The state has the highest proportion of DC fast chargers per capita and has “done a lot of work around electric school buses,” he said.

Another anomaly, particularly in the Southeast, is the split between the billions of dollars in incentives states have offered to EV and EV battery plants to locate there and their low rank on the scorecard. According to ACEEE, Georgia leads the list with $3.6 billion in subsidies to manufacturers but is No. 32 out of 33 on the scorecard.

States like Georgia are “spending a lot of money to attract these companies [but] they’re not setting up their state, setting up drivers in their state to really benefit,” Huether said. “They recognize maybe the broader economic manufacturing benefits, but not the benefits of having those vehicles in their state. We really implore them to be clear, more proactive in adopting some of these policies.”