Massachusetts energy providers, consumers and climate advocates presented contrasting visions of what solutions should be included in a clean heat standard (CHS) that is currently being developed by the state’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), as shown by public comments published last week.

The development of the standard was endorsed in the final report by the Massachusetts Commission on Clean Heat, and the DEP began development in April, soliciting initial comments from stakeholders on the scope of the process and the standard itself.

Under the basic framework, fuel suppliers would be required to acquire an increasing number of credits associated with verified reductions in emissions from heating. Credits could be bought and sold to help suppliers meet their obligations, while suppliers could also be allowed to meet their obligations through alternative compliance payments.

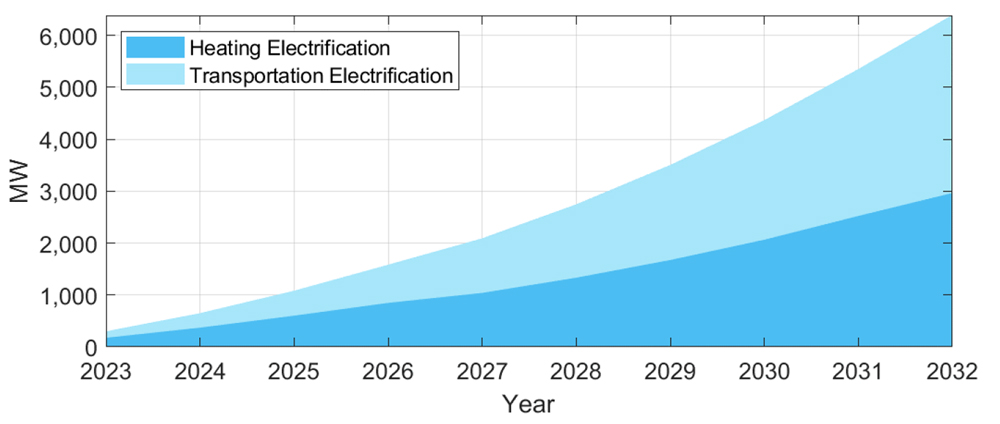

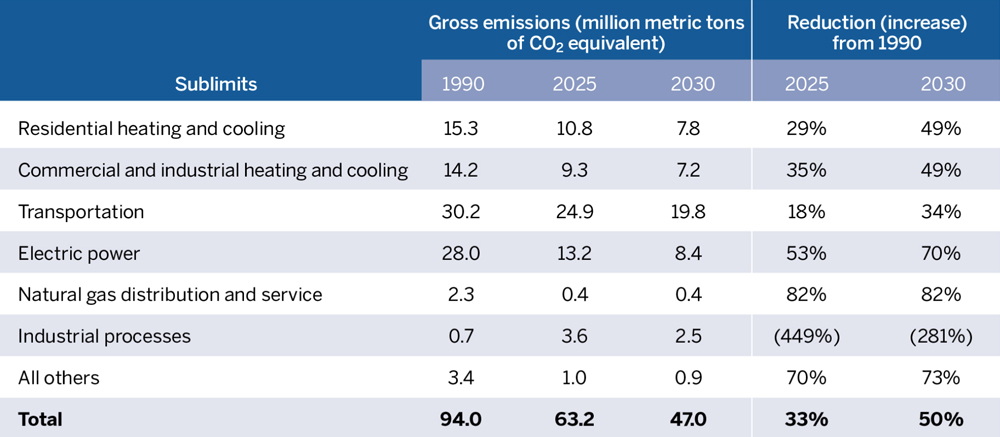

The goal of the standard is to help Massachusetts align its heating sector with its mandatory emissions limits: The state is required by law to reduce its gross emissions 50% by 2030, 75% by 2040, and 85% and be net-zero by 2050. The state also has emissions sub-limits for different heating sectors, as well as for the gas system, which are set in five-year increments.

In 2018, combustion for heating accounted for about 34% of Massachusetts’ carbon pollution, according to a report prepared for the state by researchers at the Regulatory Assistance Project (RAP), which outlined options for a CHS. The report noted that natural gas accounted for about two-thirds of heating emissions.

Defining Clean Heat

Many of the comments received by the DEP focused on whether alternative fuels should be able to generate clean heat credits.

According to the RAP report, decarbonization options include “weatherization improvements, energy efficiency improvements, heat pumps, clean district energy and other verified low-carbon options, potentially including renewable methane, clean hydrogen, biodiesel, renewable diesel and advanced wood heat.”

Fossil fuel producers and providers argued that the DEP should include a variety of options related to alternative fuels in the standard, while environmental groups said the standard should only incentivize electrification and weatherization options.

National Grid said that “electrification and energy efficiency should be the cornerstone strategies for decarbonizing buildings in Massachusetts,” but it also argued for the inclusion of combustion options within the standard.

“Alternative, low-carbon, non-fossil fuels will play an important role in ensuring families and businesses across the commonwealth have access to decarbonized heat,” National Grid wrote. “Repurposing existing infrastructure, including the existing gas distribution network to deliver low-carbon alternative fuels such as RNG [“renewable” natural gas] and hydrogen can help make the energy transition more affordable by reducing the need for new electric infrastructure construction, which will present affordability challenges.”

The Mass Coalition for Sustainable Energy — a group funded in part by Enbridge, Eversource Energy and National Grid, and whose members include the Associated Industries of Massachusetts, the commercial real estate development association NAIOP and several regional chambers of commerce — called hydrogen and RNG “viable decarbonizing pathways” for heating, adding that “we cannot take those pathways off the table.”

Meanwhile, environmental groups argued that hydrogen and RNG should not be included in the standard.

“Our top priorities for a CHS for Massachusetts are ensuring adequate equity protections and an electrification-only compliance program, particularly for gas utilities,” wrote a coalition of 37 environmental groups, led by the Conservation Law Foundation, Acadia Center, Green Energy Consumers Alliance and Pipe Line Awareness Network for the Northeast. “Alternative gases are not a long-term solution for the buildings sector, so incentives should not encourage buildout of these wasteful processes in the near term.”

Massachusetts sector sub-limits for carbon emissions | Massachusetts DEP

Massachusetts sector sub-limits for carbon emissions | Massachusetts DEP

The coalition said that the greenhouse gas emission reductions associated with replacing natural gas with hydrogen and RNG would be marginal, and that a dependence on these fuels would increase the overall costs associated with reaching net-zero emissions.

They also highlighted concerns related to the safety of blending significant quantities of hydrogen into the gas system, along with the public health impacts related to combustion.

“The commonwealth should not fund fuels like hydrogen that pose significant safety risks, when safer appliances like heat pumps are available,” Andee Krasner wrote on behalf of Gas Transition Allies’ Hydrogen and Biogas Working Group. “Hydrogen ignites more easily and has a wider explosive range than natural gas. … It can embrittle steel pipes, and hydrogen has higher permeation rates for elastomeric seals and plastic pipes.”

Krasner added that “biofuels and green hydrogen made using renewable energy have an important role in the future but should be reserved for hard-to-electrify industrial processes. They should be produced preferably on-site or, if not, then as close to the end use as possible to minimize leakage and pollution.”

The Coalition for Renewable Natural Gas — whose members include fuel producers that specialize in RNG, as well as fossil fuel producers, including Shell, Chevron, BP, and pipeline companies such as Kinder Morgan and Enbridge — argued that RNG could cover a major portion of the state’s gas needs.

“The portion of renewable gas serving Massachusetts’ gas system will increase even as total system throughput declines, eventually leading to a smaller gas system which transports only 100% clean fuels to targeted end uses,” the coalition wrote. “Given expected declines in gas system throughput, the use of renewable gas need not lead to net pipeline expansion, beyond connecting these new supply sources to existing load.”

The coalition said RNG from waste sources in Massachusetts such as landfills, manure and wastewater treatment could cover about 10% of existing residential gas demand, 11% of commercial demand or 26% of industrial demand in the state; gasification of organic matter such as agricultural and forestry residues and energy crops could nearly double this total.

While most fuel suppliers focused on alternatives to fossil fuels, Canadian fossil fuel producer Irving Oil argued that the standard should incentivize some fossil fuel heating systems.

“End-use fuel switching should be eligible as a means to comply because a lower-carbon fuel (i.e., heating oil to natural gas) is still an improvement in emission reductions and shouldn’t be discredited,” the company wrote. “Energy-efficient heating systems, including but not limited to combined heat [and] power systems that may use portions of fossil fuels should also be incentivized.”

The RAP report directly discouraged incentives for fuel switching, saying that new pipeline buildout “both adds to the fixed costs of the pipeline grid and delays the ultimate conversion of the building away from fossil fuels,” while the state’s Commission on Clean Heat concluded that “the installation of new fossil fuel equipment and services should not be supported under the CHS.”

Protecting Vulnerable Communities

Public comments from stakeholders largely agreed that the CHS needs to be designed in a way to protect lower-income residents as the costs of the transition mount.

The city of Boston said that the standard should incentivize co-benefits including air quality, workforce development, equity and resilience, and called on the DEP to take on a robust public engagement process.

“Addressing the challenges of climate change presents opportunities for advancing the wellbeing of our residents, communities and economies; a holistic approach to designing programs like a clean heat standard will help identify and take advantage of such opportunities,” wrote Mariama White-Hammond, Boston’s chief of environment, energy and open space.

The environmental group coalition called for substantial adjustments and protections for low-income customers, who represent a disproportionate share of residents of color in the state.

“Perpetuation in the medium to long term of the unmanaged transition off of gas that is already underway will be an inequitable disaster for low- and moderate-income [LMI] gas customers,” the group wrote. It also advocated for targeted protections for renters to prevent gentrification caused by building upgrades.

“Without protections for renters, landlords can use incentives subsidized by ratepayer or tax dollars like a CHS or Mass Save for building upgrades as a pretext for rent increases that force out low- and moderate-income renters from relatively affordable housing units.”

The state’s Commission on Clean Heat recommended that the DEP require fuel providers to “include a specified percentage of credits generated in LMI and [environmental justice] populations and households in their annual compliance filings.”

National Grid wrote that it supports this recommendation, along with dedicating funds from alternative compliance payments to support environmental justice communities.

The DEP will hold its first virtual public meetings on the CHS on June 20 at 10 a.m. and 6 p.m.