ALBANY, N.Y. — The 2023 New York Energy Summit last week focused on the financial, regulatory and technology landscape in the state as it presses forward with a hugely ambitious, complicated and expensive energy transition.

Opportunity tempered with challenge and uncertainty was a recurring theme in the comments of dozens of panelists and in the questions posed by scores of attendees of the April 4-6 summit.

New York’s leaders are still wrangling over key policy details, and federal guidance on how to leverage key tax incentives for clean energy finance is incomplete.

Meanwhile, despite some streamlining, the development process is still often slow and difficult in New York, and local opposition can be fierce. The grid interconnection process continues to be a bottleneck, as well.

But a confluence of factors — vision and opportunity backed by leadership and funding to make it reality — is present in New York in 2023.

Nick Addivinola, of community solar developer Nautilus Solar, observed that money is not a problem, even amid high interest rates and inflation.

“There is certainly more capital chasing projects today than ever,” he said. “There’s more capital than projects.”

The 19 presentations at the conference included discussion of New York’s landmark climate law, efforts to decarbonize buildings, grid resilience, and financing all the work that the state needs or wants to see accomplished.

High Needs

A frequent talking point at the summit was the large number of skilled workers who will be needed to carry out New York’s energy transition — more than 200,000 by 2030, according to a state estimate — and how far short of that the present workforce is.

Michel Delafontaine, president of Alternative Aviation Fuels, said the timelines specified in various state and federal laws and guidance “seem to be long, but it’s short. In terms of workforce development, we’re looking at a turnover of three to four years to form and shape folks that know what they’re doing in many aspects — electrical, pipefitting, number-crunching, legal and all the aspects of project development — and we’re short of them.”

“I can testify to that aspect,” he said. “We’re short of workforce.”

Jeffrey Andreini of Crowley Wind Services said it’s a topic that comes up often in discussion of offshore wind. “What I tell people all the time is you can have the all the assets you want, you can have all the [waterfront construction and maintenance] terminals that you want, but if you don’t have anybody that’s going to run a vessel, going to be able to do the logistics on the terminal, guess what? Nothing’s going to happen.”

Richard Lawrence of the Interstate Renewable Energy Council said this reality is sinking in as more projects go from concept to execution.

“In the 20 years I’ve been working on this, I’d say the last year has really been the first time I’ve seen companies working in this space really recognizing the challenges that it takes to develop the workforce. It’s coming up now as certainly in the top three of limiting factors to actually getting to our goals and building these projects out.”

He added: “We’re competing against every other sector that’s out there that’s looking for workers.”

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 recognizes this need, Lawrence said. He called it one of the first federal incentive/policy packages with labor and workforce development provisions baked in.

Gary McCarthy, who has pressed the Smart Cities technology initiative in his dozen years as mayor of Schenectady, said more emphasis needs to be placed on the value employees bring to an organization than to their sheer numbers.

“We’re looking for quantity now; everyone has a demand for employees,” he said. “It’s hard sometimes to step back and focus on quality; how do you do that outreach? How do you do that in a systematic way of building the rapport, getting the message and then creating the opportunity?”

New York law requires that more than a third of state spending on the energy transition benefit disadvantaged communities, and a main strategy to accomplish this will be training and employment opportunities — which are easier to mandate than achieve.

“I think the key piece here is to have really authentic organizations that have the trust of local communities partner with entities that have something to offer,” said Adam Flint of the Network for a Sustainable Tomorrow. “Transferring resources into disadvantaged communities rather than doing everything from the outside, actually hiring people to help build these programs, is a really good move.”

The clean energy sector also butts up against a multigenerational shift away from the skilled trades by a significant portion of American society, and it has trouble competing for the attention of young people entering the workforce amid the allure (and salaries) of the computer technology sector.

Both challenges are real, panelists said, but can be overcome.

The skilled trades should be introduced as a career option to children as young as 10 to 12, midway through their schooling, panelists said, and for those who are graduating now, clean energy should be framed as an opportunity to become one of the early experts in a new economy.

Also, Big Tech is currently laying workers off by the thousands, while clean energy is hiring by the thousands, Lawrence noted.

Andreini pointed to the optics of recruiting young adults to help save the planet. “We’re cooler,” he said. “At the end of the day, you’re talking about an energy revolution right now. That’s really what’s going on. I tell adults that, and they get excited. It’s got to be about more than just money.”

Major Projects

Houtan Moaveni, executive director of New York’s Office of Renewable Energy Siting, was interrupted by the only spontaneous round of applause during the summit when he said his office — a recently created entity — has issued more final siting permits in the last two years than were issued in the preceding nine years. Each took only six months on average.

Darren Suarez of Boralex later qualified that record: ORES, which works with projects rated at no less than 25 MW, moved much of the review process outside the formal permitting procedure. Including pre-permitting work, the overall time involved is still lengthy.

But that procedural standardization and streamlining has been the beneficial result of the Section 94-c law under which ORES operates, he said.

“It has the appearance of being faster, but I think the big thing for developers is it’s more certain. You know spending the money — if we do the right thing; we meet the objectives; we meet the standards — we’ll get the permit.” That was not always the case with Article 10 permitting, which 94-c supplemented, he said.

One of the biggest initiatives in New York is not in the state, but in federal waters off its coast.

Gregory Lampman, director of offshore wind at the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, said the state’s goal for offshore wind is 9 GW of installed capacity by 2035, but the OSW program folds in much more than the flow of electrons from ocean to land: It seeks to create a local manufacturing supply chain and the supporting infrastructure; develop a workforce; and coordinate transmission needs with NYISO while striking a blow for environmental justice and benefiting disadvantaged communities.

The goal is a new ecosystem with spinoff benefits.

“We’re trying to empower the whole of manufacturing capacity in the state of New York,” while simultaneously competing with neighboring states for finite resources and collaborating with them to expand availability of those resources, Lampman said.

And how is that working out with the 27 OSW leases up and down the Atlantic Coast?

“We probably are far short of where we need to be, but we are moving forward because there are economic pressures to develop that supply chain,” said Jim Bennett, a senior adviser at the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

He said BOEM’s focus is now transitioning from leasing to project review and approval.

“In the past three years, we’ve doubled the number of people we have on board, which for a federal agency is pretty impressive, but during that same time, our workload has increased fivefold,” Bennett said.

With the expansion of variable wind and solar power generation, New York needs a large amount of energy storage capacity: It has set a near-term goal of 6 GW, the most of any state, but eventually will need significantly more, some of it the long-duration type that is not yet technologically mature.

This, along with the domestic manufacture incentives of the IRA, could create a new industry sector in New York, said William Acker, executive director of the New York Battery and Energy Storage Technology Consortium.

“This is going to be a real catalyst to grow the economy in New York state,” he said.

In the wake of the supply chain disruptions of 2020 and 2021, there has been great interest in domestic manufacturing, said Michael Slattery of Agilitas Energy. “I can’t speak to the precise amount of batteries that will come into New York, but I think New York is very well positioned — as is any state that has a large industrial base and a hefty demand for the output.”

Slattery said he might be more pessimistic than most on the subject, but he expects domestic demand to outstrip domestic production for three to five years.

“It is a huge, huge logistical challenge to get these factories built,” he said.

Acker touched on a subject he has raised before: The present structure of New York’s electricity market makes large-scale energy storage uneconomical.

“The new programs that the state is bringing forward might level that playing field, but right now there isn’t really much traction,” he said. “It was mentioned earlier: We have great goals in this state, but actual deployed projects at the bulk level have been pretty minor.”

Hurdles and Hiccups

Tens of thousands of megawatts of clean energy capacity is on the drawing board in New York state, but many projects will never advance beyond that stage. This divide was a frequent topic at the summit.

Panelists touched on the long and winding road that connects inspiration and execution in New York state government, as competing interest groups delay or reshape the laws and regulations needed to bring grand goals such as decarbonization to reality.

New York’s landmark Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act — which set many of the goals the state and its energy sector must now reach — was signed into law nearly four years ago but is still mired in planning and sometimes heated debate.

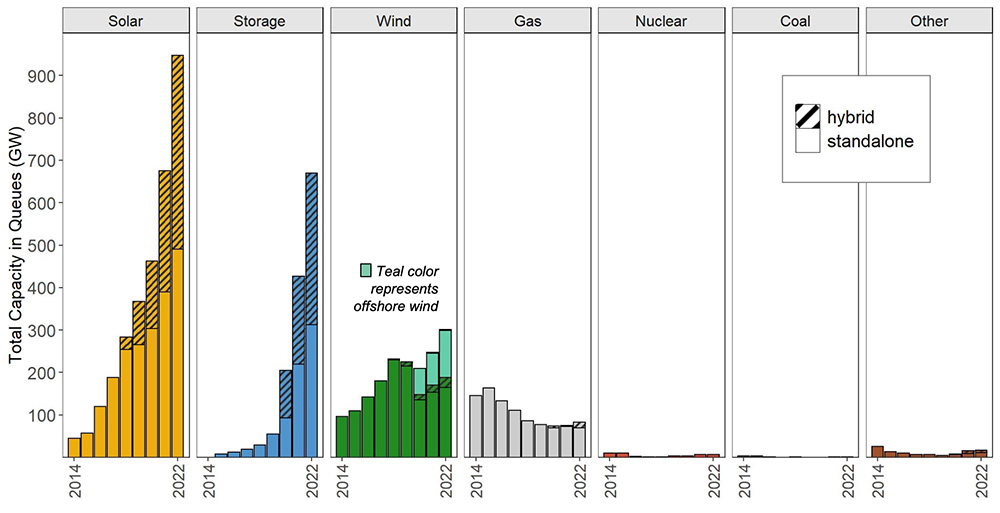

State leaders are fond of pointing out that the CLCPA mandates 70% of the state’s power come from renewable energy by 2030, and that the project already in NYISO’s interconnection queue would bring the state to 66%. But some of those projects will never break ground.

“Projects haven’t been built for a variety of reasons. One of those certainly is interconnection,” Boralex’s Suarez said.

“We look at what’s in the queue now, [and] we actually see all the projects the state would need to meet, basically, its objectives. A lot of those projects won’t come to fruition for a variety of reasons, some of them as a result of timing or economics, or sometimes they’re purely speculative. Sometimes some developers may have more than one project that they’re putting in multiple interconnection queues.”

NYISO is trying to speed up the process and reduce some of the speculative activity, Suarez said, but the volume of applications is unprecedented, and the ISO is not set up for it. The most recent Class Year was one of NYISO’s largest ever, he added, and many projects had to go to FERC to seek additional time to get into it.

Moderator Ingo Stuckmann, of the Zero Emission Think Tank, asked his panel about those economic challenges, such as triple-digit price increases for substations and multiyear wait times for transformers.

Suarez said the long lead time between contracts being signed and work starting on projects proved harmful in 2022. “There is a real disconnect at this point between what the expectations were three years ago and what the reality is now, and unfortunately we’re confronted with that reality.”

Marguerite Wells of Invenergy said, “I think you see that too in the conclusion of the last [NYISO] Class Year, where half of the projects rejected their cost allocations, which means they’re out of the Class Year, and they’re either going to shut down or going to have to go through a new Class Year and hope for a better cost allocation.

“I think that’s a really significant indicator of how … these costs are impacting project economics,” she added.

Moving Forward

New York has a strong home rule tradition, and while some authority to approve renewable energy projects has been moved to the state level, local support remains important to the clean energy transition.

Winning hearts and minds is apparently something many of the panelists have put a lot of thought into; they offered the audience numerous suggestions on building community support.

Job creation is often touted by energy developers, but that is not a compelling argument to the local residents who stand up at a town hall meeting and say they just do not want to look at a solar array, said Amy McDonough of New Leaf Energy — particularly given that most of the jobs created are temporary construction positions.

“The bigger picture — what this renewable energy economy means to the state, not just this project in their town, but this project and the next project and the next project — that kind of messaging and education could potentially be helpful,” she said.

White Plains Mayor Thomas Roach said building that city’s large community solar program relied on the help of organizations trusted in the community, such as El Centro Hispano.

“They actually had volunteers entering people into the system so they could take advantage of the discounted electricity because a lot of people are intimidated by the process,” he said.

That type of outreach can be important with something like community solar, which may sound suspiciously like a scam to someone who receives a cold call solicitation, said Sandhya Murali, co-founder and COO of Solstice.

Suarez threw in a plug for expanding New York’s transmission grid, which would make it possible to site renewable energy in more of the state, and not overwhelm a relatively small number of communities with solicitations just because interconnection is possible there.

“Increased transmission can actually increase social acceptance to some of those projects,” he said.

Wells suggested focusing locally instead of globally, emphasizing economic development rather than climate change, “in terms of the renewable energy industry committing to the communities in which it works.”

As is often observed, there are two New Yorks: New York City is densely populated, heavily Democratic and unable to host a meaningful amount of clean energy generation. Beyond the New York City suburbs, most of the state is more conservative, less densely populated and has a much lower median income.

The open space upstate is ideal for solar farms and wind farms spread across thousands of acres, but many upstaters resent having to look at power lines, wind towers and solar arrays.

“In a lot of these communities, climate change doesn’t exist in the minds of many constituents,” Wells said. “So, I don’t talk about climate change as a driver for my work; I talk about economic development. Because it is the other half, and the money that these projects generate is very significant in terms of making a difference in the lives of upstate communities that don’t have a lot of other revenues.”