The EPA on Wednesday released proposed emissions standards that are expected to speed the transition to electric vehicles and avoid nearly 10 billion metric tons of CO2 emissions. (See EPA to Propose Major New Emission Standards for Cars and Trucks.)

Most of the cuts from the proposed standards are for light- and medium-duty vehicles, which produce a greater volume of emissions and have more readily available alternatives to the internal combustion engine, but EPA also proposed new standards for heavy-duty vehicles.

“Today’s actions will accelerate our ongoing transition to a clean vehicles future, tackle the climate crisis head on, and improve air quality for communities all across the country,” EPA Administrator Michael Regan said at an event announcing the standards outside the agency’s headquarters.

EPA expects the rules for light- and medium-duty vehicles will cut 7.3 billion MT of CO2 between 2027 and 2055 and projects net benefits of $1.6 trillion. The heavy-duty vehicle rules would save 1.8 billion MT of CO2 and yield $320 billion in benefits.

The proposed standards for light-duty vehicles start in 2027 and ramp up to an 82 grams of CO2 per mile standard by model year 2032, while the medium duty standard ramps up to 275 grams per mile by 2032. Those represent cuts in fleet average CO2 emissions of 56% and 44%, respectively, compared to the model year 2026 standards, EPA said.

Heavy-duty vehicles have different standards depending on the type of vehicle covered, with EPA updating existing standards for 2027 and extending more stringent cuts out to model year 2032.

The standards are expected to drive significant increases in the EV share of the vehicle market, although the fact that they are technology-neutral should also drive improvements to internal combustion engines and benefit other technologies such as fuel cells.

In light of the rules, EVs are forecast to make up to 67% of light-duty sales by 2032 and 44% of medium-duty sales by that year. EVs are expected to account for 8.4% of light-duty sales this year, up from just 2.2% in 2020.

Automobile manufacturers have already said they plan to switch to producing larger volumes of EVs in the coming decades. Based on those pledges and current market shares among automakers, EVs should make up 48.6% of sales by 2030. Regan said that the agency was following the market trends, which shows the standards are achievable.

“I believe that because when I look at the projections that many in the automobile industry have made — his is the future,” Regan said. “The consumer demand is there. The markets are enabling it. The technologies are enabling it.”

The EPA’s standards provide a regulatory compliment to federal incentives from recent legislation, including the Inflation Reduction Act, Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the CHIPS and Science Act, which include tax credit and other funding for electrification, Regan said.

The Alliance for Automotive Innovation, which includes major automakers such as Ford and General Motors, agreed that the industry was electrifying but called EPA’s plan “aggressive by any measure.” Reaching the target depends on factors outside of automakers’ control, the group said.

“Factors outside the vehicle, like charging infrastructure, supply chains, grid resiliency, the availability of low carbon fuels and critical minerals will determine whether EPA standards at these levels are achievable,” it said.

Impacts to the Grid

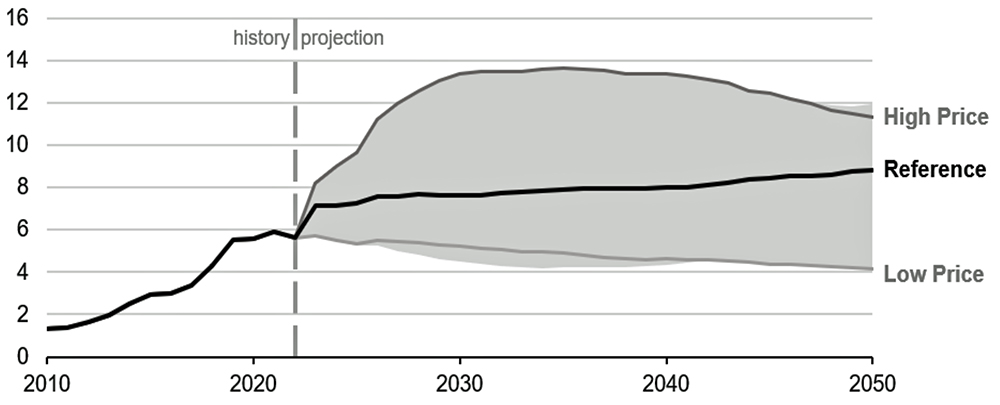

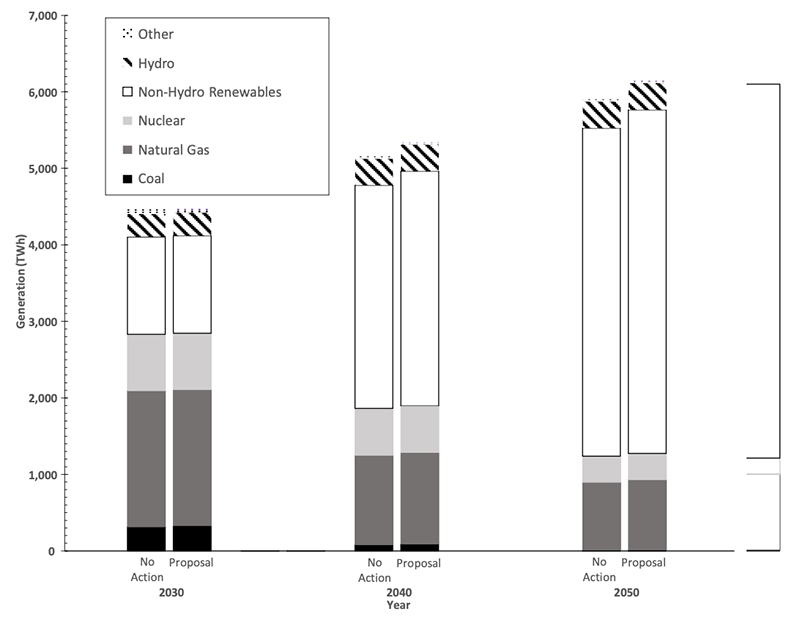

EPA’s modeling predicts non-hydroelectric renewables becoming the largest overall source of electric generation by 2035, at about 46% of total generation, rising to 70% by 2050.

“As [power plant] emissions continue to decrease between 2028 and 2050 due to increasing use of renewables, and as vehicles increasingly electrify, the power sector GHG and criteria pollutant emissions associated with light- and medium-duty vehicle operation will continue to decrease,” the agency said in its light- and medium-duty rulemaking.

Light- and medium-duty vehicle rule’s impact on power generation | EPA

Light- and medium-duty vehicle rule’s impact on power generation | EPA

The additional electric vehicles will not increase electricity demand significantly, according to EPA, ranging from an increase of less than 0.4% in 2030 to about 4% in 2050. The heavy-duty rule would add another 0.1% of demand in 2027 and 2.8% in 2050. That demand growth is much smaller than what the industry dealt with as air conditioning grew in popularity, or more recent demand growth associated with the digital revolution.

“The U.S. electricity end use between the years 1992 and 2021 increased by around 25% without any adverse effects on electric grid reliability or electricity generation capacity shortages,” EPA said.

The light-duty rule highlighted analysis in California, which has found that 20% of charging loads at any time in the day can be shifted to another hour in a process that benefits car owners, other customers and the grid at large.

“Integration of electric vehicle charging into the power grid, by means of vehicle-to-grid software and systems that allow management of vehicle charging time and rate, has been found to create value for electric vehicle drivers, electric grid operators and ratepayers,” the rule said. “Management of PEV charging can reduce overall costs to utility ratepayers by delaying electric utility customer rate increases associated with equipment upgrades and may allow utilities to use electric vehicle charging as a resource to manage intermittent renewables.”

The new cars will require new charging infrastructure, with 12 million home chargers expected in 2027, increasing to more than 75 million in 2055, while workplace chargers will grow from 400,000 to 12.7 million, and public chargers will grow from 110,000 ports to more than 1.9 million.

Other infrastructure will be needed to integrate the new demands, such as upgrades to local distribution systems. But EPA found significant uncertainty on exactly what would be needed and asked for comments to weigh in on the subject.

Reactions

The rules elicited opposite reactions from the country’s two main political parties, as seen from statements from the leadership of the Senate Environment and Public Works (EPW) Committee that oversees the EPA.

“In addition to providing regulatory support to where the market is already heading, EPA’s proposed vehicle emissions standards would make significant progress in our fight against climate change,” EPW Chair Tom Carper (D-Del.) said.

“They will also save Americans money at the pump and better insulate our country from the volatility of the global oil market. I am encouraged by the Biden Administration’s step toward cleaner, more efficient cars, trucks and vans, and I hope to see a final rule by the end of the year.”

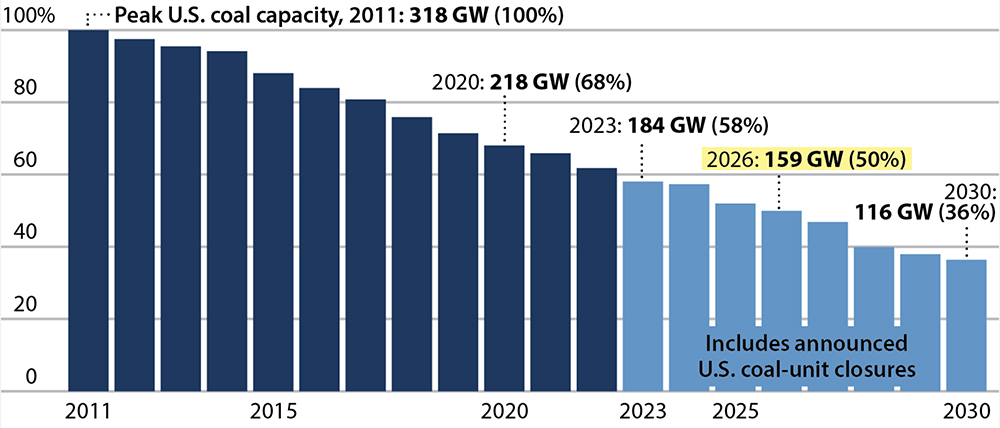

Ranking member Rep. Shelley Moore Capito (R-W. Va.) blasted the rule and said it made little sense when coupled with other actions that are shutting down “baseload” coal and natural gas plants.

“Today, the Biden administration made clear it wants to decide for Americans what kinds of cars and trucks we are allowed to buy, lease and drive,” Capito said. “These misguided emissions standards were made without considering the supply chain challenges American automakers are still facing, the lack of sufficiently operational electric vehicle charging infrastructure, or the fact that it takes nearly a decade to permit a mine to extract the minerals needed to make electric vehicles, forcing businesses to look to China for these raw materials.”

Likewise, reactions among clean energy groups were largely positive, while the American Petroleum Institute lambasted the rule.

“This deeply flawed proposal is a major step toward a ban on the vehicles Americans rely on,” API CEO Mike Sommers said. “As proposed, this rule will hurt consumers with higher costs and greater reliance on unstable foreign supply chains.”

The American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy argued that EPA should have gone even further than it did.

“These are strong proposals, yet they do not give us as much progress as climate circumstances demand,” ACEEE Transportation Program Director Shruti Vaidyanathan said. “We need to move to electrified vehicles as rapidly as possible while continuing to reduce emissions from conventional vehicles, and these proposals need to be improved to get us there.”