More than 1,700 of New York’s 4,918 census tracts are slated to be designated as disadvantaged communities (DACs), prioritizing them for future state and federal resources to address environmental justice issues as the state advances its clean energy transition.

On Monday, New York’s independent Climate Justice Working Group, which was created by the state’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, unanimously approved the final environmental, population, geographic, health, historical and individual criteria for determining the 35% of census tracts that will be designated as DACs. (See NY CJWG Poised to Select a 35% DAC Coverage Threshold.)

The final criteria, which were developed in consultation with state agencies, environmental justice groups and the public, are based on 20 environmental and climate risk indicators, including pollution exposure, proximity to waste or processing sites, and flood risk. The criteria also consider 25 population and health indicators, including education, race, health sensitivities or housing, as well as individualized considerations for low-income households.

Overview of CJWG calculations of criteria indicators to achieve census tract score | New York DEC

Overview of CJWG calculations of criteria indicators to achieve census tract score | New York DEC

The criteria also included the 19 census tracts that are federally designated as more than 5% tribal and indigenous land.

Several indicators were considered but not included in the final criteria, including prevalence of diabetes or lead contamination data, but these factors could potentially be considered for future evaluations.

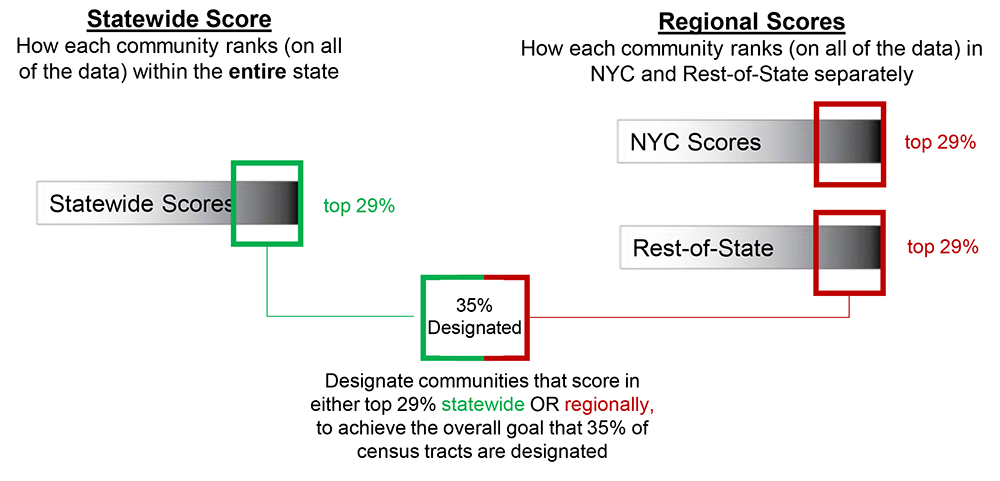

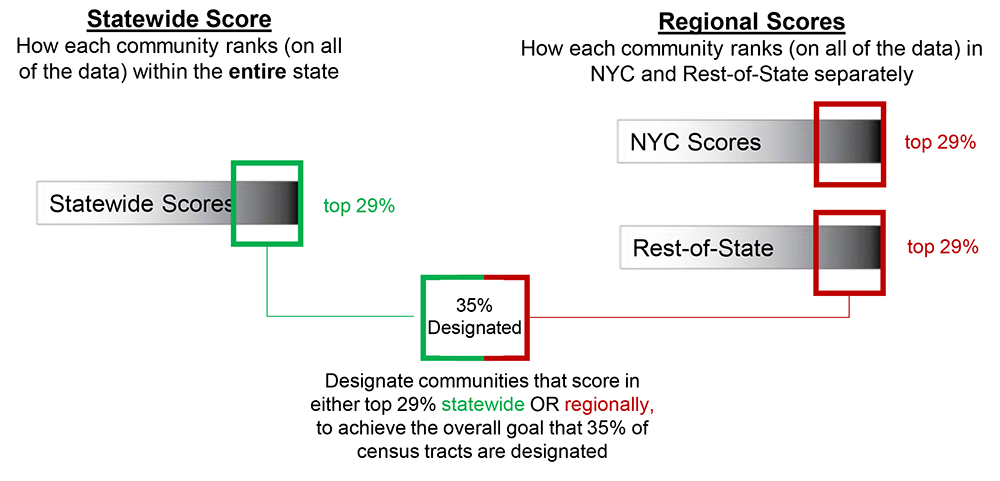

Designating DACs was done through a process where weighted factor scores, which were calculated from indicator percentile ranks, were combined into two weighted component scores that were then added together to generate an overall score.

Census tracts whose overall score was in the top 29% of either statewide or regional scores were then designated as a DAC.

Roughly a dozen other tracts that contained at least 100 people but had insufficient census data to obtain appropriate scores will be designated as DACs.

The CJWG’s approval of the final criteria is a significant step in addressing evolving environmental risks and historical burdens by ensuring future clean energy or climate-resilience projects go to communities most in need.

The CJWG will review the DAC criteria annually to consider updating the indicators or methodology and track how DAC provisions are being implemented. It will discuss this iterative process at its meeting on April 4.

Public Support

CJWG member Sonal Jessel, director of policy at the environmental justice group WE ACT, said she voted in favor of the criteria because even if the CJWG did not “fill in all the gaps,” the group “did really great due diligence in moving through all of the concerns that came in.”

Top 29% of census tract scores either statewide or regionally designated as a DAC | New York DEC

Top 29% of census tract scores either statewide or regionally designated as a DAC | New York DEC

Jill Henck, clean energy program director with the Adirondack North Country Association, voted yes because, as a rural area representative, she appreciated how members were “cognizant of the fact that New York is a unique state,” and made efforts to include stakeholders living in rural communities just as much as those in New York City.

Eddie Bautista, executive director at NYC Environmental Justice Alliance, said CJWG members “all get the period of time we’re living in and understand that climate change will affect everyone, but its impacts are not evenly felt, and the [approved criteria] is a big step to rectifying that.”

Elizabeth Furth of the New York Department of Labor said the votes of approval ensure “disadvantaged communities throughout New York State can realize the many benefits from our transition to a green economy.”

Two CJWG members, who despite voting in favor, took time to share several issues about the criteria in its current form.

Rahwa Ghirmatzion, executive director at PUSH Buffalo, spoke on behalf of the Seneca Nation of Indians, who submitted a letter that outlined significant concerns, particularly about industrialization near their territories and representation.

The Tribe wrote that it rejects “the idea that destruction of territory can be offset by benefits provided by the state or a developer,” and the “cumulative impacts of industrial development on the nation, its cultural resources, and its environment cannot be counterbalanced by economic development, financial support, jobs or other forms of monetary financial benefit.”

Elizabeth Yeampierre, executive director of UPROSE, a Brooklyn-based sustainability organization, was disappointed that diabetes, which can disproportionally impact disadvantaged populations, did not make it into the final criteria.

However, Neil Muscatiello, director at the Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Epidemiology at the New York Department of Health, emphasized during his vote that, although there were “limitations and gaps,” these can all be addressed in the next annual update and diabetes will be among the first considered.

CJWG Chair Alanah Keddell-Tuckey cast her affirmative vote saying she was proud to work with a group who “did not create these problems,” but were “willing to stand up regardless of the pushback and criticism to fix the thing that they did not break.”

Keddell-Tuckey said there were “cynical” people who, particularly during the pandemic, “lay the blame on the victims, rather than admit we were dealing with generations of redlining, income inequality and malicious zoning practices.”

Basil Seggos, commissioner of the Department of Environmental Conservation, said in a statement after the vote that the CJWG’s work ensures “no less than 35% with the goal of 40% of the Climate Act’s benefits are directed to disadvantaged communities.”

Doreen Harris, CEO of the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, said “the final adoption of this criteria solidifies New York State’s commitment to climate justice for those underserved communities,” and the CJWG’s “clearly defined guidance will help us realize the equitable distribution of benefits from clean energy investments.”