Agriculture contributed more than 11% of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in 2020, and the Biden administration has allocated nearly $20 billion in new funding authorized by the Inflation Reduction Act to expand local and regional soil and water conservation programs, as well as reduce emissions.

The Natural Resources Conservation Service, an agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, last fall announced the first competitive grants would be available in six separately funded programs. The initiatives are designed to foster sustainable agricultural practices under the rubric of “climate smart” harvests.

Proof of sustainable practices will also be a key component in low-carbon ethanol for aviation and in numerous other agricultural-based chemicals and products.

Carrie Pearson, Cargill Corp. | AURI

Carrie Pearson, Cargill Corp. | AURI

Federal mandates on carbon are coming in one form or another, say agricultural and food-marketing experts.

“I think it’s coming,” Carrie Pearson, product sustainability lead at Cargill, said of federal rules requiring agribusiness to provide evidence about the environmental impact of food products.

“If you look at the Inflation Reduction Act, there are incentives for products that have lower footprint and environmental product declaration data available,” she said last month during a webinar produced by the Minnesota-based nonprofit Agricultural Utilization Research Institute (AURI).

Kate Barry, Chainalytics | AURI

Kate Barry, Chainalytics | AURI

Kate Barry, an expert on food packaging and senior consultant with Atlanta-based supply chain consulting firm Chainalytics, agreed, but she added that she did not expect federal rules immediately. “I see them coming in five to 10 years. I think we are a long way from being able to control at the farm level.”

The road to lower carbon in food and fuel begins on the land, whether a few hundred acres in a small farm or thousands of acres in a corporate farm.

“IRA provides unprecedented funding levels targeted to improve soil carbon; reduce nitrogen losses; [and] reduce, capture, avoid or sequester carbon dioxide, methane or nitrous oxide emissions associated with agricultural production,” NRCS said in an initial request for comments.

Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities

Key to the success of the new programs is a long-practiced NRCS “ground up” approach to encourage buy-in from small farmers and ranchers.

USDA describes its existing Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities as an effort to help farmers and ranchers in 30 states align agricultural conservation practices with the growing market demand for food grown or raised in a climate-friendly environment. NRCS has awarded $2.8 billion in initial grants to 70 projects through the program.

The broad initiatives — including the availability of new climate-smart financing, new efforts to reduce livestock methane emissions, an emphasis on increasing individual farm participation in carbon sequestration techniques and the overarching emphasis on local involvement — have already caught the attention of existing trade organizations, as well as entrepreneurial farmers and ranchers.

Jared Knock, AgSpire | AURI

Jared Knock, AgSpire | AURI

One such entrepreneur who has embraced sustainable practices and won initial USDA funding is Jared Knock, a college-educated, 25-year South Dakota farmer and rancher and employee at Millborn Seeds, the nation’s largest supplier of cover crop and grass seeds.

Knock and his associates at Millborn created a second company, AgSpire, three years ago to promote cooperation between farmers and ranchers to improve grazing land, encourage growth in cover crops and reduce the over-reliance on synthetic fertilizers.

In a January webinar produced by AURI, Knock said AgSpire’s team includes agronomists and grazing specialists to advise ranchers about soil-building management and the best seed mixture of regenerative grasses and cover crops for fields temporarily taken out of grazing.

The company also has developed a program to assist farmers who want to produce low-carbon corn as a feedstock for low-carbon fuel, Knock said.

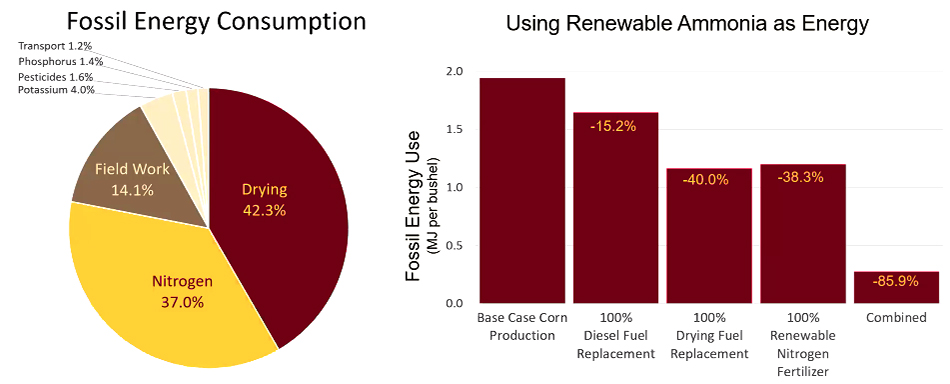

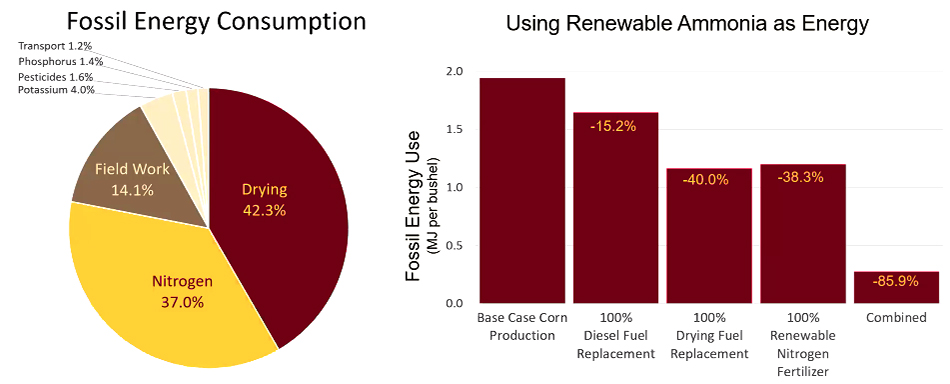

The impact of corn production on the environment could be sharply reduced by replacing diesel fuel, using renewable nitrogen fertilizer and replacing the fuel used to dry the harvest. | AURI

The impact of corn production on the environment could be sharply reduced by replacing diesel fuel, using renewable nitrogen fertilizer and replacing the fuel used to dry the harvest. | AURI

AgSpire is a partner in five projects receiving initial USDA grants, including one focused on improving ranch grazing lands with extensive use of rotating cover crops; one to produce low-carbon aviation fuels; another to sell climate-smart, low-climate-impact feed corn; and a project to expand the production of low soil-impact seed grains.

“We are a segue between the farmer and rancher and helping them to understand what opportunities they have,” he said. “We are also working with [food] companies to understand how to engage with the farmers and put programs into practice. The Climate-Smart Commodities application process was a good opportunity.”

The program is also focused on engaging food retailers.

Cameron Wallace, Land O’ Lakes | AURI

Cameron Wallace, Land O’ Lakes | AURI

Cameron Wallace, an executive at Land O’Lakes subsidiary Truterra, said the company’s new climate-smart partnership with USDA will enable it to dramatically scale up its already extensive programs connecting farmers with retailers.

“Today we have over 2 million acres in our platform and over 53 local retailers. We feel like we are uniquely positioned to operate on a national scale and to help provide support and capabilities to ensure that growers can implement climate-smart practices, sustainably and in a profitable way that helps them improve their yields and their productivity as well,” Wallace said.

“Our goal through our climate-smart partnership with USDA is to continue to scale those programs to increase the capabilities and [market] access across the country, both in row crop operations, as well as livestock and dairy operations, to increase financial support and technical support [to farmers] … to enable the scaling of markets as more and more food companies are trying to meet their sustainability goals,” he said.

Scott Herndon, Field to Market | AURI

Scott Herndon, Field to Market | AURI

Field to Market, a D.C.-based alliance of growers, conservation groups, universities and agribusiness organizations, is already working on a national scale to create an agricultural supply chain based on sustainability. It has won a $70 million Climate-Smart grant.

“Our premise is that no one sector can achieve sustainability on their own,” said Scott Herndon, president of the alliance. “That is why we bring all sectors of the value chain together.”

He said the alliance’s financing programs — the basis of the USDA grant — have been designed “to incentivize the adoption of sustainable agriculture,” including “blended financing models or green bonds” offering reduced interest rates for sustainable production.

Ashley McDonald, National Pork Board | AURI

Ashley McDonald, National Pork Board | AURI

Ashley McDonald, assistant vice president for sustainability at the National Pork Board, which has also been awarded a Climate-Smart grant, said the pork industry is aiming to reduce its GHG emissions by 40% by 2030.

Reaching that goal involves enrolling as many of the nation’s hog farms as possible in an analytical study to develop best practices across the industry, using data from participating members, she said, adding that the board intends use its USDA grant in new financing programs to assist farms adopt sustainable practices.

Measuring the Carbon Impact of Sustainable Practices

The underlying assumption that adopting sustainable practices will reduce carbon dioxide and other GHGs will have to be measured, and agronomists are already trying to figure out how to do it.

Joel Tallaksen, University of Minnesota | AURI

Joel Tallaksen, University of Minnesota | AURI

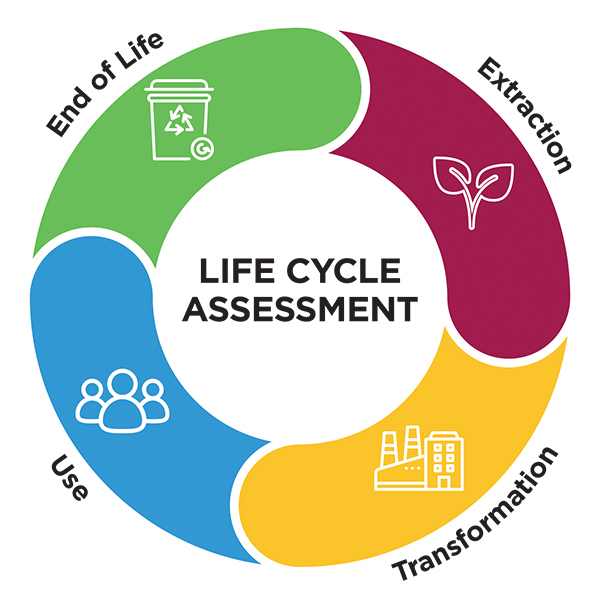

One analytical tool that has been used is a life cycle assessment (LCA), a kind of accounting methodology designed to look at the environmental impact of a manufactured product, said University of Minnesota scientist Joel Tallaksen.

“LCA is very holistic, going from the extraction of resources all the way through production and end of life,” Tallaksen said. “Now, the nice thing about LCA is that it can examine multiple environmental issues. So, you can look at things like fossil energy greenhouse gases, but you can get very specific and look at some detailed topics.

“The biggest challenge in LCA work is getting data on different systems, especially in agriculture. Once you have all that data, then you can begin to model how that data is going to fit together. LCA is really an accounting methodology, and it focuses on noneconomic issues. So, we can gather a lot of data and use that data to look at environmental impacts and some of the other impacts the system might have,” he said.

Analytical tools used by manufacturers to calculate environmental impact are being used cautiously to as first step to estimate agriculture’s climate impact. | AURI

Analytical tools used by manufacturers to calculate environmental impact are being used cautiously to as first step to estimate agriculture’s climate impact. | AURI

That is the way the tool is used in manufacturing. Agriculture is a bit trickier, Tallaksen said. “Agriculture deals with biological systems, and they’re very different from going into a factory that’s making staplers. …

“But when you start dealing with biological systems, there are complex interactions that you must think about. In agriculture, you’re talking often about soil type, moisture [and] temperature,” factors that will determine how fast reactions occur, he said.

Another complexity in figuring agricultural emissions is that often the impact of a crop must be allocated to a number of commodities that are ultimately marketed,” he said. “If you find out there’s a certain amount of greenhouse gas being produced, but it’s going into two different products, you have to figure out how to divide that impact between the two products,” he said.