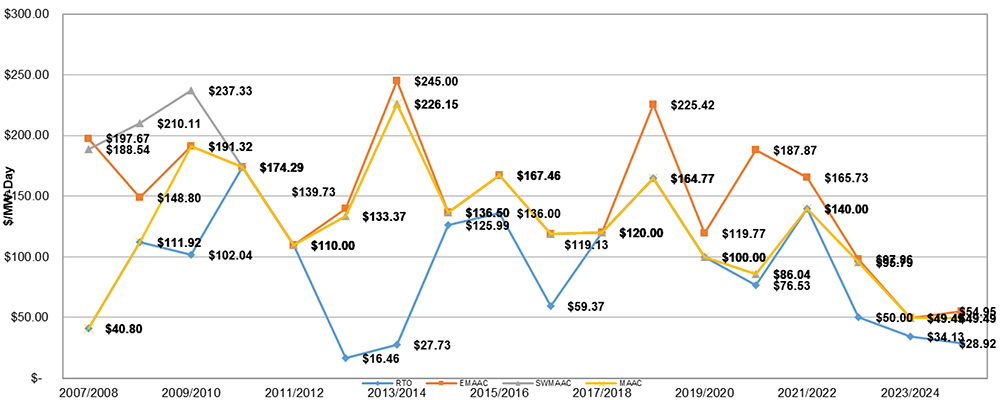

Electricity markets might need to change along with the shift to more renewables in the industry, but speakers on an OurEnergyPolicy webinar yesterday argued they were still the best way to make that transition reliable and affordable.

Some have claimed that the transition to markets has been difficult for the old monopoly utilities in the states that have opened their markets, but Emily Sanford Fisher, the Edison Electric Institute’s executive vice president for clean energy, is not among them.

“The answer is ‘no’; I think they’ve responded well,” Fisher said. “It’s been, you know, 20, maybe going on 30 years since some of these restructurings have occurred. But I think one of the interesting impacts that we haven’t focused on is the supplier-of-last-resort obligation.”

In every restructured state except for Texas, utilities are the provider of last resort, and significant shares of small, mass-market customers still take service from them. The utilities have to buy power to ensure that they can meet that demand, plus any customers who come back to their service from a competitive firm, Fisher said.

Texas has gone the farthest with restructuring, and its old utilities in the ERCOT market are effectively wires-only companies now, with the provider-of-last-resort obligation covered by competitive retailers.

“We are equal participants in these markets,” Fisher said. “Some of the discussion often sounds like we live in two worlds: There’s an [investor-owned utility] world, and then there’s a competitive market world. We’re all part of that same sort of ecosystem, but our ability to plan for and to make sure that we are able to provide power to customers is sometimes challenged by that construct.”

Restructured states generally do not allow utilities to directly own generation, but Fisher noted that has started to change in states like Massachusetts that want to see major investments in offshore wind. Utilities’ balance sheets are better able to handle those major, upfront investments, she added.

While utilities can help build massive infrastructure projects, the industry has many more options to supply customers than it used to in the past, said Robert Dillon, executive director of the Energy Choice Coalition.

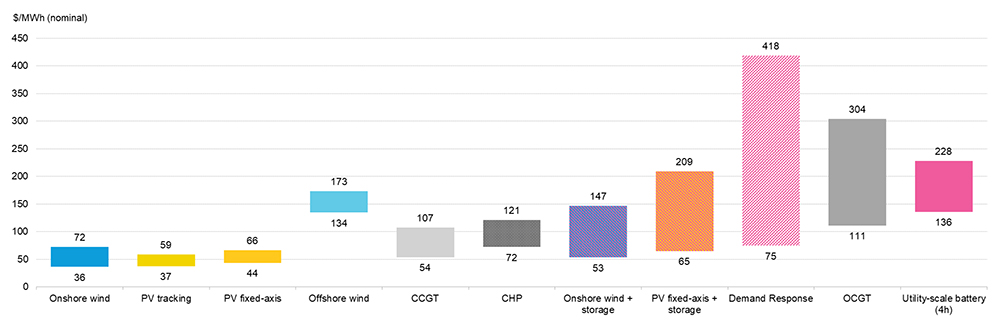

“They place a bet on one technology, and the market is changing so rapidly, that a lot of times they’re betting on the wrong technology,” Dillon said.

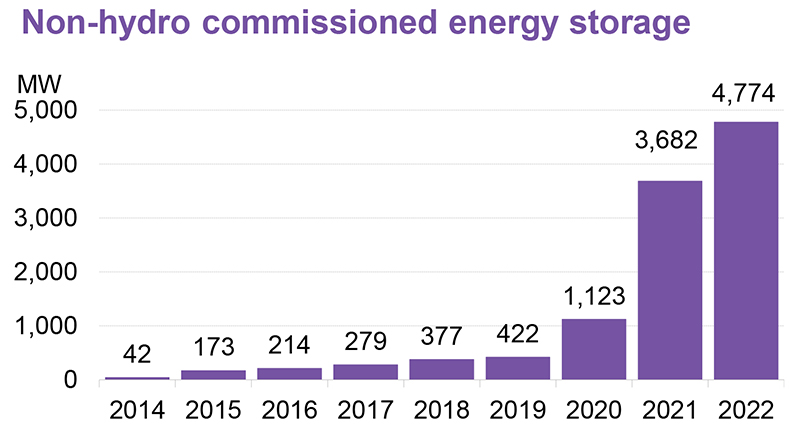

The private sector is able to invest in a broad array of different technologies that can help improve flexibility and reliability, including the distributed technologies that customers are investing in themselves, he added.

“I think the existence of competition and generation makes sense,” Fisher said. “I think there’s a benefit that has allowed us to bring new technologies into the market.”

Renewables were probably going to grow anyways, but the combination of markets and state renewable portfolio standards has driven much of their deployment, Fisher said. Renewables are cheap to deploy now, but other technologies such as hydrogen or advanced, long-duration storage are going to be needed to get to a 100% emissions-free grid, and Fisher said utilities are in a good position to help them become commercially competitive.

Locking in too many decisions now could prove to be a bad bet for the future given that power plants are meant to last for decades, noted Conservative Coalition for Climate Solutions Vice President of Public Policy Nick Loris.

“We don’t necessarily know what the future generating sources that are most affordable, reliable and clean will be,” Loris said. “And the more that the government locks resources in unproductive places with specific tax subsidies to specific energy technologies, it makes it all that more difficult for them to compete in the marketplace.”

The Inflation Reduction Act’s clean energy tax incentives transition to just a “clean incentive” that is not technology specific starting in 2025, which should allow “all the flowers to bloom,” Fisher said.