ALBANY, N.Y. — Key policy and funding decisions being made now will shape New York state’s clean energy transition, but regardless of the specifics, a significant workforce investment will be needed, advocates said Wednesday.

The Alliance for Clean Energy New York (ACE NY) held a briefing on its legislative priorities as state budget negotiations intensify and invited speakers from two organizations that are training some of the estimated 200,000 new workers needed for the transition.

A handful of the state’s 213 lawmakers were in the audience for the event, held a month shy of the statutory deadline for passage of the 2023-2024 state budget.

Gov. Kathy Hochul presented her plan Feb. 1. A series of legislative budget hearings followed, and Senate and Assembly leaders are expected to produce their counterproposals soon. Closed-door negotiations will produce a final budget that not only allocates a pile of money — Hochul’s proposal totals $227 billion — but codifies a range of policy decisions that might face tougher prospects for passage if voted on separately.

ACE NY, which advocates for clean energy on behalf of business and organizations in that field, is just one of many of the advocates lobbying for its priorities as the details are hammered out this month.

But with New York pressing one of the most ambitious climate protection plans of any state, and being one of the most expensive states in which to carry such plans out, the details will impact residents’ wallets and quality of life for decades to come.

ACE NY Executive Director Anne Reynolds said transmission constraints and the often lengthy review process facing renewable power developers are key problems to address if the state is to meet its goals.

Of the 137 projects awarded contracts by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority since 2017, only 20 are operational, and they are small, representing just 3% of the combined 13.62 GW capacity of the projects. The 15 projects that were canceled make up 6% of the total.

“NYSERDA’s been doing an excellent job awarding these contracts on an accelerated basis and the projects are creeping their way through this process, but it’s a long one and we have a long way to go,” Reynolds told attendees.

Among ACE NY’s 2023 legislative priorities is a directive that the New York Power Authority propose projects to ease the top three transmission-constrained zones, as identified by NYISO; speeding up the process by which developers mitigate impacts on endangered and threatened species; and the exclusion of alternative energy production facilities from what the organization calls a duplicative permitting process under Sections 68-70 of the state Public Service Law.

“In the budget negotiations, the thing that we’re watching the most are the cap-and-invest policy, the Build Public Renewables [Act] and the all-electric buildings,” Reynolds told RTO Insider after the meeting. If all three are in both the Assembly’s and Senate’s budgets, she said, the measures will have momentum going into final negotiations. “Then it’s game on with respect to those pieces.”

ACE NY is opposed to the governor’s version of Build Public Renewables because it would give a renewable energy development role to NYPA. This would put NYPA in unfair competition with the private sector, when it should instead be concentrating on transmission development, the organization argues.

Next Generation

Vincent Albanese of the New York State Laborers’ Organizing Fund highlighted workforce development as another potential sticking point.

Officials mapping out New York’s energy transition estimate that more than 200,000 new jobs will be created in the process, many of them in skilled trade. The scoping plan for the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act of 2019 repeatedly flags the need for workforce development.

Vincent Albanese, New York State Laborers’ Organizing Fund | © RTO Insider LLC

Vincent Albanese, New York State Laborers’ Organizing Fund | © RTO Insider LLCAside from the effort of training workers, there is also the task of recruiting people in a state that is losing population.

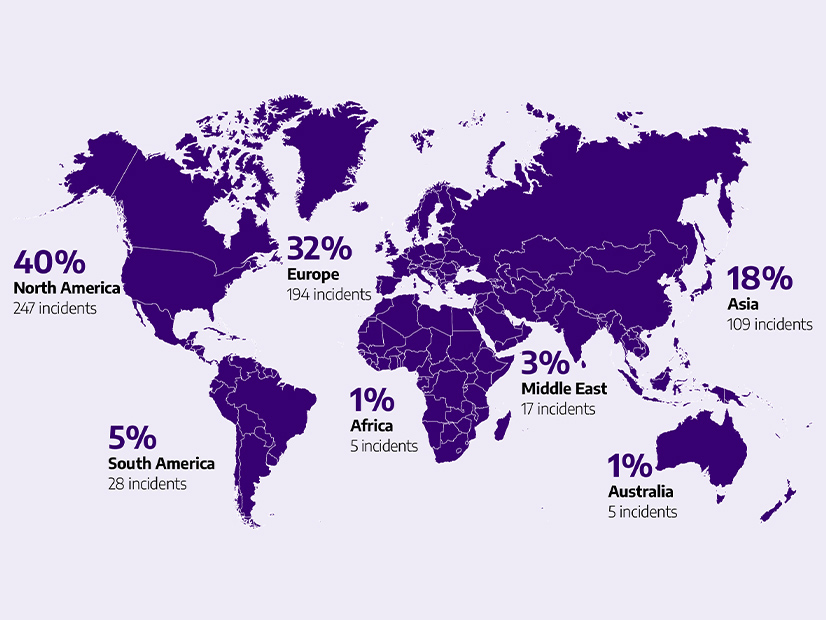

Albanese displayed a map showing New York state’s population centers: most of them downstate, some spreading north along the Hudson River and west along the Erie Canal. Then he overlaid a map of renewable energy projects: most of them upstate, many of them dozens of miles from the nearest population center.

“One of the biggest challenges that we’re facing is most of these jobs, at least on the generation side, are located in parts of New York that are incredibly rural and not densely populated,” he said. “People have major challenges getting to these jobs, dealing with childcare [and] all sorts of transportation issues.

“If we can’t solve this problem, none of this happens,” he added.

Many new green jobs will of course be in those population centers: electrifying homes and transportation, for example. But other challenges exist there.

New York is targeting 35 to 40% of the benefits of the energy transition to disadvantaged communities, including through job training, but legislation would not erase the legacy of those disadvantages.

Jennifer Lawrence, Social Enterprise And Training Center | © RTO Insider LLC

Jennifer Lawrence, Social Enterprise And Training Center | © RTO Insider LLCJennifer Lawrence, executive director of the Social Enterprise and Training (SEAT) Center in Schenectady, said her organization takes on these challenges. Its young clients will not emerge from the YouthBuild program as journeyman carpenters, for example, but they will have the hard skills to enter the workforce and the soft skills to advance in the workforce.

SEAT has been collaborating with the laborers union, which has training centers in the Albany-Schenectady region, and with East Light Partners, which has a 20-MW solar project nearby, to acclimate young workers to the industry and the labor organizations that work in it.

“It’s also going to build a sense of community and their future perspective,” Lawrence said, “so they’ll be able to think about, ‘I can fit into this culture; I can do these jobs; I can apply to this when I’m done.’”

Albanese said other efforts by the union across the state specifically target groups as diverse as formerly incarcerated people and political refugees from Burma. In Buffalo, he said, Local 210 and EDF Renewables set up a fund to pay incoming trainees for four weeks while they attended a boot camp of sorts before starting their actual apprenticeship.

“We hope that this could be a model with a lot of other developers,” he said. “This has been a really successful program.”

But there are other barriers that a stipend cannot bridge. Older workers near the top of pay scale have cars and are accustomed to long commutes, while young workers just starting out may not. The union does not have a solution for everything, Albanese said.