After New York’s Climate Action Council (CAC) voted Monday to approve the scoping plan to guide implementation of the state’s 2050 climate goals, questions remain about how much of the plan can be implemented through agency rulemaking and what will require new legislation. (See New York Climate Scoping Plan OK’d.)

The principle behind the scoping plan is to “reduce GHG emissions consistent with the interim and long-term directives established in” New York’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA).

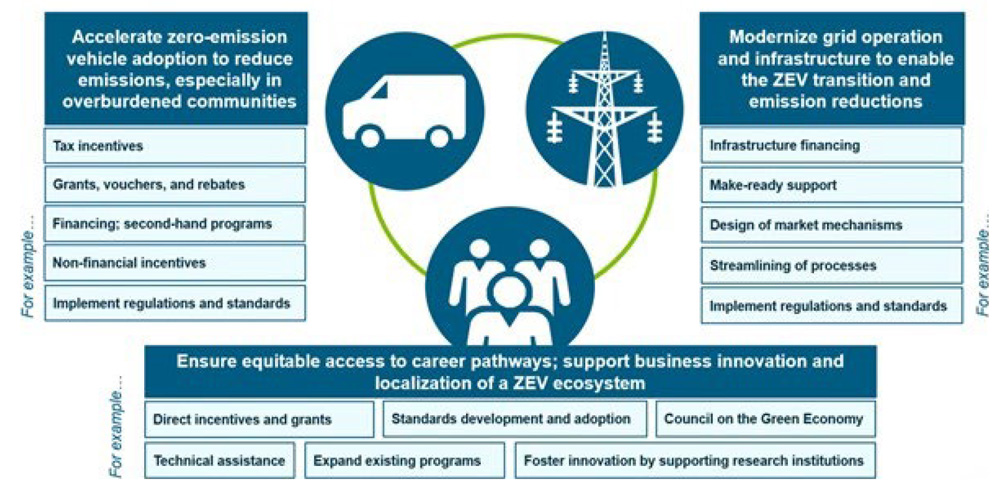

The plan seeks to achieve “deep” emissions reductions by targeting sectors reliant on fossil fuels, such as buildings and transportation, while electrifying the state through heat pump installation, purchase of electric vehicles, and development of technologies that “manage energy use and reduce energy costs.”

Integration analysis conducted by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) found that deep decarbonization by 2050 is feasible and will create hundreds of thousands of jobs.

NYSERDA’s analysis suggests that the cost of inaction could be more than $115 billion, while climate action costs incurred by New York could represent only 0.6% of the state’s economy in 2030 and 1.3% in 2050, with many of those costs offset by federal contributions. (See CAC Inches Toward Final Scoping Plan, Shares IRA Impacts, NYSERDA Study: Ground Source Heat Reduces Peak, but Cost Impact Unclear, and NY Considers Role for New Nuclear Generation.)

The plan suggests enormous net benefits from climate action: creating stronger and more resilient energy systems; cleaner and healthier homes; high-quality jobs; and a more equitable future.

Many of the recommendations in the scoping plan are “big, bold and visionary,” Basil Seggos, Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) commissioner, said at Monday’s meeting.

Sectoral Approach

The plan advances the CLCPA “both within and across economic sectors,” including transportation, buildings, electricity, industry, agriculture and forestry, waste, land use, local government, adaptation and resilience, and the gas system. Its most important recommendation is the implementation of an economywide cap-and-invest program that ensures CLCPA “emission limits are met while providing support for clean technology market development.”

The plan recommends that New York adopt this “innovative program design,” which limits emissions by forcing fossil fuel generators to buy allowances for their pollution. But a cap-and-invest program would require approval from the legislature, whose members may resist a market intervention, despite Democratic majorities that support such climate efforts.

The scoping plan also provides a framework that agencies can use to “develop a coordinated gas system transition” and ensure the “transition is equitable and cost-effective for consumers without compromising reliability, safety, energy, affordability and resiliency.”

Natural gas use was another contentious subject for the CAC, with climate justice advocates calling for a near ban on the fuel and protesting certain gas definitions, while gas advocates argued that every option should be on the table when it comes to decarbonization. (See NY CAC Debates the ‘Nomenclature’ of Natural Gas.)

Both cap-and-invest and the proposed gas system transition will face legislative hurdles, since many consumers, particularly in Northern and Western New York, depend on fossil fuels and will oppose any limits.

Climate Justice

The scoping plan was also developed to ensure the transition addresses the “health, environmental and energy burdens that have disproportionately impacted underrepresented or underserved communities … and to remedy the structural causes that underpin these burdens.”

Related recommendations, based on the Disadvantaged Communities Barriers and Opportunities Report, “address past practices that excluded historically marginalized and overburdened communities from state decision-making processes.”

The CLCPA mandates that disadvantaged communities (DACs) receive at least 35% of the benefits of climate spending. It places investments in five key areas identified in the scoping report as critical to offsetting historical marginalization: energy affordability, environmental overburdening, equitable and sustainable job growth, localized development of clean resources, and inclusive DAC involvement the implementation processes.

Many measures related to achieving climate justice can be accomplished through state or city agency rulemaking and regulation, as exemplified by the DEC’s recently finalized rules related to air permits and climate change consideration.

But other measures, particularly those reversing historical underinvestment in DACs, require legislation, as exemplified by Local Law 97. (See NYC Proposes Rules to Implement Building Emissions Law.)

Economic Opportunities and ‘Just Transition’

CAC members had debated workforce and business development across the state and what that development would look like, who it should predominantly benefit, and where it should be targeted. (See ‘‘Family-sustaining” Union Jobs, New York CAC Debates Inclusion of Blue Hydrogen, Union Jobs in Plan.)

The plan calls for “the advancement of a low-carbon and clean energy economy that results in new economic development opportunities across New York and a just and equitable transition for New York’s existing and emerging workforce.”

The plan pushes for the development of clean technology manufacturing that targets those less fortunate by building out a “robust clean technology supply chain in New York.”

The recommendations for a “just transition” provide direct support for displaced workers, apply consistent labor standards across all industries and promote workforce training opportunities for new economic activities. The plan also calls for creation of an Office of Just Transition and a Work Support and Community Assurance Fund.

Those entities would guide policymaking related to supporting transition-impacted communities by spurring job growth — particularly union jobs — and leveraging financial resources for workforce training and business development.

The plan says “union labor is important to [CLCPA] implementation,” calling for agencies to “work with workers and their unions to ensure jobs created as a result of the state’s energy transition are good union jobs.”

Next Steps

The scoping plan will now be incorporated into the State Energy Plan and updated every five years by the CAC.

The plan moves to the DEC, which has until Jan. 1, 2024, to “draft and promulgate enforceable regulations to ensure that the state meets the Climate Act’s statewide GHG emission limits,” as well as publish an implementation report every four years measuring the success of emission reductions policies.

After July 1, 2024, the Public Service Commission (PSC) will be required to issue a biannual review of the plan’s renewable energy program, which will include progress reports on the programs “the PSC has established to require procurement of 9 GW of offshore wind by 2035, 6 GW of solar PV by 2025, and 3 GW of energy storage by 2030.”

The PSC will also provide regular updates on how DACs have benefitted from the plan’s implementation.