A more than $2 million New Jersey study that will look at whether crops and cows can thrive next to bifacial vertical and rotating solar panels is moving ahead even as the state is nearly a year behind in the legislature’s timeline for implementing rules that will govern dual-use solar projects, also known as agrivoltaics.

The New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station (NJAES) is on track to complete construction by April, David Specca, assistant director of Rutgers University’s EcoComplex, said at the New Jersey Farm Bureau’s annual conference in Princeton on Nov. 15.

Crop trials will begin immediately after, and initial results from the study could be ready in a year, said Specca, who heads the Rutgers Agrivoltaics Program.

The study will be carried out at three sites around the state, two of which will study the growth of crops beneath a 337-kW, single-axis tracking system of 695 solar panels that rotate as the sun moves from East to West. Aside from improving energy production efficiency, the rotation will give the crops — including soy beans, hay and vegetables — a more evenly spread exposure to shadow and sun than would fixed panels, Specca said in an interview with NetZero Insider.

The third site, with 378 solar panels and a capacity of 179 kW, will study the experience of cows grazing next to vertical bifacial panels. “Our observations are going to be of the grass and forage crops [that] are being grown for feed for the animals,” he said, adding that researchers will also look at how the cows react, such as whether they graze contentedly in that environment and whether they prefer the shade from the panels or direct sunlight.

Agrivoltaics, which enables the land below or around solar developments to be used for farming, has proven successful in other parts of the country but is still largely an unproven quantity in New Jersey. The study comes amid friction in New Jersey and other states over the merits of using farmland for solar projects, with some farmers wary that solar projects will eat up farmland and weaken the farming sector, and others concluding that solar projects could provide already struggling farmers with another revenue stream — especially if that can be done side by side with crop cultivation or animal rearing.

The tension over solar use of farmland is heightened in some parts of New Jersey by the loss of farmland to the voracious demand for logistics and e-commerce warehouses that serve the Port of New York and New Jersey and the New York market. But that pressure also heightens the attraction of agrivoltaics, which can provide revenue without destroying farms or permanently assigning farmland to another use, as do warehouse developments. (See NJ Solar Push Squeezes Farms.)

Peter Furey, executive director of the Farm Bureau, said that Specca’s presentation showed “some real promising activity.” He said he has no doubt that farms and solar projects can cohabit the same space and be productive, but that doesn’t mean the concept will work.

“Is it financially feasible?” he said. “Well, the answer to that remains to be seen.” Given the high cost of solar equipment and installation, a key factor will be the incentive structure laid out by the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities (BPU), he said.

Developing Rules

What that will look like is still pending. More than a year after Gov. Phil Murphy signed a law, A5434, that required the BPU, in consultation with the state Department of Agriculture, to adopt rules and regulations for a pilot dual-use solar program within 180 days, the program has yet to emerge. The legislation set aside $2 million for the agrivoltaics study.

The pilot program, as set out in the law, would establish a framework for the “construction, installation and operation of dual-use solar energy projects that are connected to the distribution or transmission system owned or operated by a New Jersey public utility or local government unit and located on unpreserved farmland.”

The law limits the annual capacity of all projects in the program to 200 MW and will restrict each project to no more than 10 MW. The rules will define the incentives available, and the law requires the BPU to convert the pilot to a permanent program between 36 and 60 months after the rules are approved by the BPU and Agriculture Department.

BPU staff are currently “in the process of developing the program and do not have a timeline to share for release at this time,” said spokesman Peter Peretzman.

More imminent are the rules for another program that will affect farmland use, the Competitive Solar Incentive (CSI) program, which are expected to be released in the coming weeks. The program uses a competitive solicitation process to allocate incentives for grid-scale solar projects, those larger than 5 MW. Draft rules released earlier in the year included guidelines on what land can be used for such projects and the steps needed to mitigate the impact on the land of an approved project. (See NJ Tries to Balance Solar Growth vs. Farmland Protection.)

Furey said the agricultural and solar sectors are waiting for them to drop.

“The law put parameters limits on how much farmland can be used for industrial-scale solar,” he said, and the official release of the rules will start the process of developers thinking “about whether they want to come out on farmland.”

Grid Connection Impact

New Jersey’s initiative comes amid other advances toward implementing dual-use programs in the Northeast. Sheep grazing on solar array lands has already shown some success, and the possibilities of pairing solar with beekeeping, crops and even cattle is under scrutiny, according to speakers at the Renewable Energy Vermont conference in October 2021. (See Overheard at REV2021: Cattle, Crops, Bees Trend in Agrivoltaics.)

New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) said in August that developers that incorporate agrivoltaic strategies would get a “favorable scoring credit” in the state’s annual solicitation for large-scale renewable energy. (See NY Scorecard Makes Way for Utility-scale Agrivoltaics.)

Dual-use solar has proven successful in other, sunnier and drier parts of the country, Specca said. But its efficacy in New Jersey, “where there’s less sun but a lot of indirect light” because of the light bouncing off the frequent cloud cover, is still not clear, and the impact of that is part of what the study will determine, Specca said.

One thing that is already clear in New Jersey is that the feasibility of an agrivoltaic project may be determined by where it is in the state, and the availability of connections to the grid, he said.

“A lot of the areas in rural parts of the state don’t have very big wires, big electric service. And so it really limits how much [electricity] can be exported,” Specca said. That won’t affect grid-scale projects, which often install their own cabling to the grid, but for smaller farms looking to set up solar projects, “that’s where these constraints would come in,” he said.

Dual-use Legal Battle

The BPU’s delay in setting up an official agrivoltaics pilot comes as the agency is in litigation with the developers of two private projects: the 18.8-MW Washington Solar Farm in Washington Township, and the 17.6-MW Quakertown Solar Farm in Franklin Township.

In each case, the project has secured local approvals and about half of it is up and running. The two developers want the BPU to award them incentives under the state’s Transition Incentive Program, funds that would enable them to develop the second halves of the project as a mini-pilot program that will study the impact and benefits of agrivoltaics.

Part of the BPU’s argument against the effort, however, is that the state pilot program will soon be in place and there is no need for a small independent pilot to run in “parallel.”

The BPU denied the two projects petition for incentives on Dec. 1, 2021, agency spokeswoman Tracey Munford said. An appeal of the board’s order “is pending before the Appellate Division,” she said, adding that the BPU would not comment further.

The developers argued that dual-use solar meets the criteria of an “innovative technology” under program rules, and so should be eligible not only for incentives, but for a high level of incentive, under the program rules.

“Petitioners urge the BPU to consider dual-use agrivoltiacs as an innovative technology that will play an important role in New Jersey’s solar future,” an attorney for the two projects, Mark S. Bellin, wrote in a June 4, 2021, petition to the BPU, laying out the developers’ case.

“The establishment of these pilot projects would give the BPU the ability to monitor and evaluate the performance of the dual-use solar farm as more than just a concept, more than just a classroom experiment,” Bellin wrote. The project would also provide a “a substantial means of delivering a meaningful number of megawatts towards the state goals and preserving farmland simultaneously.”

“The projects represent a short-term solution for the evaluation of the dual-use agrivoltaic concept at the same time as it promotes local agriculture, provides employment and municipal revenues,” according to the petition. “Creating this dual-use pilot program is a successful scenario for every stakeholder affected by the process.”

The land parcels beneath the two projects are no longer being used for farmland, Bellin argued, adding that “each of the property owners has indicated that if the complete buildout of the solar farm is not permitted, each will develop the property residentially or commercially.”

As a result, “the ability to preserve the ground for agriculture will be forever lost unless the solar use is preserved,” he wrote.

But the board on Dec. 1 rejected the petition, saying it was “duplicative and moot.”

“The goals and benefits of establishing a robust dual-use pilot program simply cannot happen in the limited context of evaluating the projects here, no matter how well intentioned,” the board said. It added that allowing the developers to create a pilot program “in parallel” to the one that the BPU will develop under the new legislation would “unnecessarily strain agency resources.”

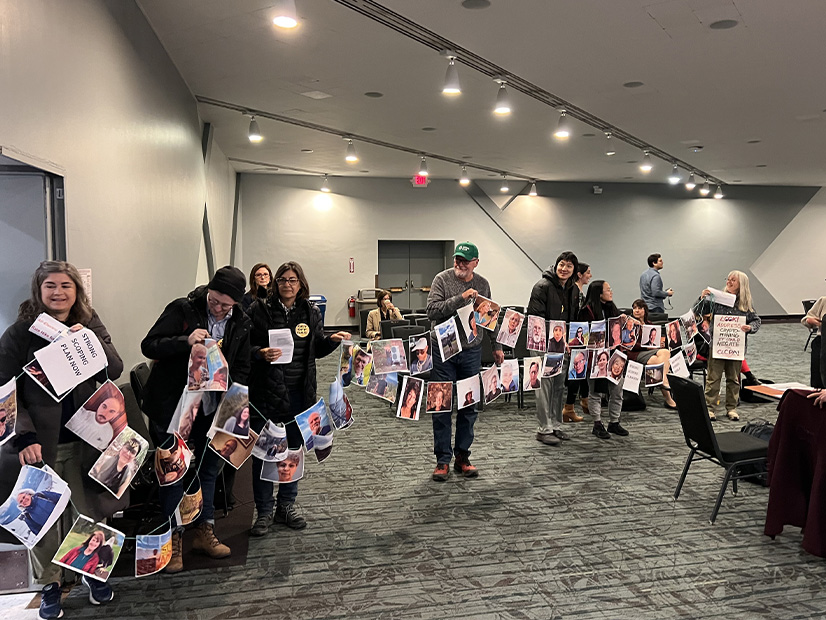

Climate protesters call for the end of gas usage in New York. | Allison Considine, Sierra Club

Climate protesters call for the end of gas usage in New York. | Allison Considine, Sierra Club