Washington needs to do a large amount of legwork to prepare for Gov. Jay Inslee’s mandate banning the sale of new gas-powered cars by 2035, according to interviews with various state officials.

Inslee announced the mandate in August, later California adopted its own Advanced Clean Cars II rules, which will bar the sale of gas-powered passenger vehicles in that state beginning in 2035. Washington is one of 17 states that follow California’s tougher vehicle emission standards, rather than the less-stringent federal ones.

“This is a critical milestone in our climate fight. … We’re ready to adopt California’s regs by end of this year,” Inslee tweeted at the time.

The governor’s action builds on a 2008 state law that sets carbon emissions-reduction targets of 45% below 1990 levels by 2030, 70% by 2040 and 95% by 2050. A 2021 Washington Department of Ecology report put the state’s CO2 emissions at 99.57 million metric tons in 2018 and showed that from 2016 to 2018 the transportation sector was the largest contributor at nearly 45% of emissions.

“Electric vehicles are the key technology to decarbonize road transport, a sector that accounts for 16% of global emissions,” a September 2022 International Energy Agency report said. “Recent years have seen exponential growth in the sale of electric vehicles together with improved range, wider model availability and increased performance.”

In broad terms, the state of Washington has two targets regarding gas-powered cars. In its last session, Washington’s legislature set a target of 2030 to encourage residents to wean themselves from gas-powered vehicles. This is not a mandate, but a goal to strive for, Anna Lising, Inslee’s senior climate policy adviser, told NetZero Insider.

“If you don’t have a goal out there, you don’t have the sense of urgency that it needs,” said Rep. Jake Fey (D), chair of the state’s House Transportation Committee.

Sen. Curtis King, ranking Republican on the Senate Transportation Committee, said Inslee and the state government cannot precisely enough predict how the use of EVs will evolve through 2035 to intelligently apply a mandate. “I don’t think it’s reasonable. I don’t think it is necessarily rational. I don’t see how you can foresee all of the challenges of that sort of mandate,” King said in an interview.

Uncertain Journey

For Washington, the road to 2035 has yet to be mapped out.

The state government does not know how many new charging stations and types of new chargers will be needed by 2035. Sources of electricity and building the extra capacity to deliver that power have to be addressed. Budget estimates have not been calculated. An electric vehicle council of 10 state agencies has been set up to do this sort of planning, but it is still in the organizational stages.

“As often in public life, we’re building an airplane while we’re flying it,” said Sen. Marko Liias (D), chair of the Senate Transportation Committee.

A study to tackle those questions is in the works, but its findings won’t be delivered to the legislature until December 2023, according to Lising and Loren Othon, alternative fuels program manager at the Washington Department of Transportation.

At least three types of EV chargers must be considered in any plan, including those at drivers’ homes that can operate overnight, chargers at workplaces where employees can power up their vehicles over a workday, and charging stations for traveling vehicles along highways. The federal government is partly addressing charging stations along interstate highways through the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) funding program. (See West Coast NEVI Plans to Charge up I-5 … and Beyond.)

Ideally, stations of at least four chargers each should be located every 50 miles along the state’s highways, Othon said, a view that aligns with NEVI program requirements. She noted that Washington’s highways weave into remote corners of the state — through places like isolated small towns such as Twisp deep in the Cascade Mountains, Republic near the Canadian border, and Walla Walla alone in southeast Washington.

Rural Eastern Washington will find meeting the 2035 target especially challenging with its very small number of electric cars and charging stations.

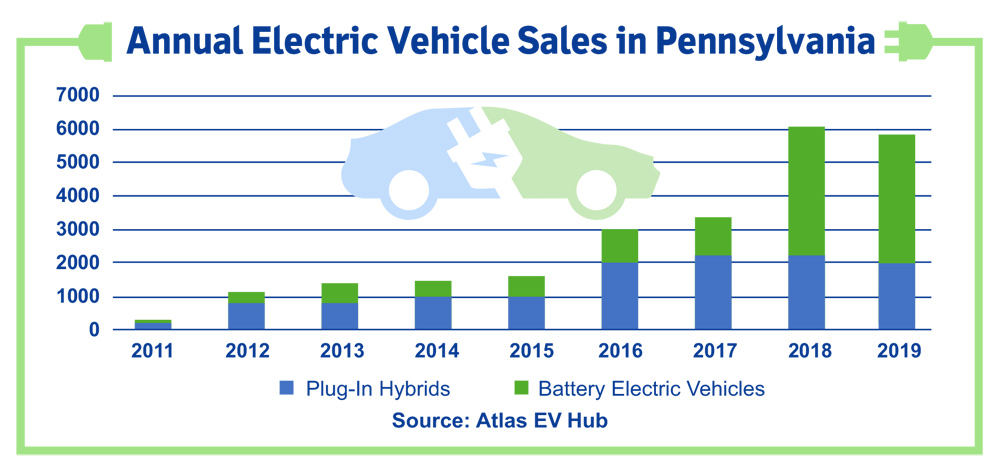

Washington has roughly 2.8 million registered cars, the 11th highest number in the U.S. The state had about 109,000 EVs in mid-October, according to the Washington State Department of Licensing. That is the fourth highest number in the nation behind California, Texas and Florida, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

King County and Puget Sound are home to the bulk of Washington’s electric vehicles, according to figures from Washington’s Department of Transportation. King County had 56,252 electric vehicles, followed by Snohomish County at 11,972 and Pierce County at 8,357. Thurston, Kitsap and Whatcom counties had between 4,105 and 2,811 electric vehicles.

East of the Cascade Mountains, Spokane County had the most electric vehicles at 2,778, followed by Benton County at 1,347.

Othon noted that people are anxious about being caught in rural areas without chargers. The ranges of the 10 cheapest electric cars vary from 100 to 275 miles, according to reviews by “Car & Driver.” Meanwhile, businesses are reluctant to install charging stations in rural areas with few customers, Othon said.

“We’re in a chicken and the egg situation, and we need more chickens and eggs,” she said.

Othon, Lising, Liias and Fey acknowledged that market developments will be also factor into whether Washington achieves its 2035 goal.

“We’ve seen the price of electric vehicles drop precipitously,” Lising said. Fey said those prices need to shrink to levels to where lower-income people can afford them.

“Passenger electric cars are surging in popularity,” the IEA report said. “The IEA estimates that 13% of new cars sold in 2022 will be electric. … However, electric vehicles are not yet a global phenomenon. … Electric car sales reached a record high in 2021, despite supply chain bottlenecks and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Compared with 2020, sales nearly doubled to 6.6 million (a sales share of nearly 9%), bringing the total number of electric cars on the road to 16.5 million.”

Prices for EVs are still prohibitively high for many drivers. The “Car & Driver” reviews show that the second to 10th cheapest models of electric cars range from $30,750 to $42,525. The cheapest model — the Nissan Leaf — sells for $28,495 with a range of 149 miles between charges. Expanding the Leaf’s range to 226 miles costs an extra $5,000.

Grid Support

During last spring’s session, Washington lawmakers appropriated $69 million to build charging stations and other infrastructure in areas of obvious need. Although the full formal report on the state’s electric vehicle needs — and accompanying financial estimates — is not due until December 2023, legislative leaders expect bits and pieces of information be released during the 2023 session that begins in January. Liias and Fey said some preliminary groundwork around additional stations could be tackled next year while waiting for the full report.

King says hybrid vehicles have been ignored by the legislature and thinks incentives for them should be addressed in the 2023 session. He also worries that a push for new charging stations will take money away from maintenance of highways and bridges.

Liias and Fey don’t believe state taxes and fees will significantly increase to pay for new charging stations and grid infrastructure. They and Lising said revenues generated by the state’s cap-and-trade program, passed last year, will likely pay for much of the infrastructure costs. Fey speculated that funding for other state decarbonization programs might have to be sacrificed to pay for the charging stations.

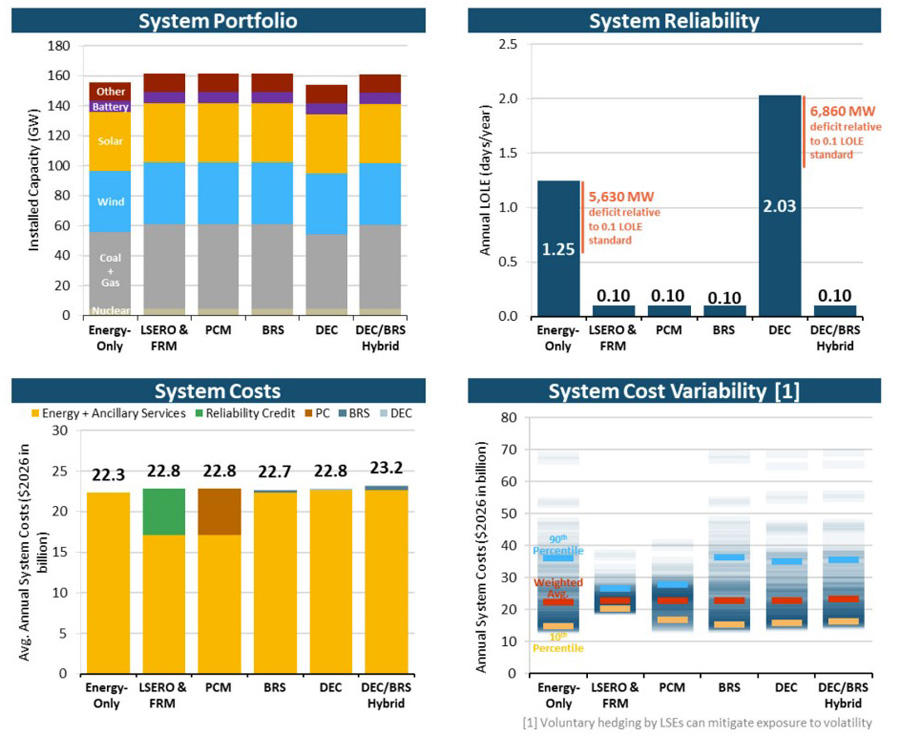

Washington will also have to address whether it has enough electricity to power the vast number of new charging stations envisioned to be in place by 2035, Fey and King said. “We’ve got to make sure the grid is set up properly,” Fey said.

King added that the manufacture and disposal of electric cars’ batteries needs to be studied. The state needs to look at the carbon footprint of mining lithium for car batteries and of manufacturing, as well as identifying locations and protocols for burying old batteries, he said.

“Those are elements that no one wants to talk about,” King said.