The New Jersey Board of Public Utilities (BPU) is opposing a bill that would more than triple the size of the state’s heavily oversubscribed community solar program, saying the expansion could stress an already overloaded grid and “bring everything to a screeching halt.”

Chance Lykins, the BPU’s director of government affairs, told the state’s Senate Environment and Energy Committee on Nov. 3 that the capacity increase outlined in the bill — from the 150 MW a year at present planned by the BPU to 500 MW a year — would have a series of consequences that could negatively impact agency solar programs.

Lykins made his comments at the first committee hearing of the bill (S3123), which was introduced Oct. 3. The committee did not vote on the bill. The hearing came as the BPU works to create a permanent community solar program, which will award incentives for 150 MW of capacity annually, after two rounds of pilot programs that together drew more than 650 applications and awarded 240 MW of capacity.

“This is one of the programs we’re most proud of,” Lykins said. “Because it both moves us towards our clean energy goals, while simultaneously helping us with our equity goals.”

Yet the agency is concerned about the impact of “moving these caps up so quickly,” he said. “We have to set these caps based on costs, on what the grid can support, on what the developers can do. … We think 150 megawatts is the correct cap for now.”

Sen. Bob Smith (D), the committee chairman and one of two primary sponsors of the bill, disagreed, saying the program’s success suggests it should be made bigger given the state’s goals.

“It is time to start thinking about a new allocation, in my opinion, because you already have the first one going and going well,” Smith said.

The proposed expansion highlights underlying tensions in the state’s solar programs that pit a desire by some stakeholders to expand rapidly against other stakeholders’ concerns about the cost, uncertain impact on other programs and logistical challenges.

The bill garnered support from solar developer Solar Landscape, solar software developer Arcadia, the Chamber of Commerce of Southern New Jersey, the mid-Atlantic representative of the Solar Energy Industries Association and the League of Conservation Voters.

But the New Jersey Division of Rate Counsel expressed concerns about the proposed expansion, saying it “had almost-certain potential for increasing costs to ratepayers.”

Director Brian O. Lipman, in a Nov. 2 letter to the BPU, said that forcing the agency to award such a large capacity each year would reduce its “ability to assure robust competition” between projects and make it difficult to ensure that incentives go to “projects that best serve the state’s clean energy goals.”

“Reducing the board’s ability to harness competitive processes in the community solar program may be in the interests of certain segments of the solar industry, but it is not in the best interests of ratepayers or the state overall,” Lipman said.

“In order to achieve the state’s clean energy goals, it is important to get the most ‘bang for the buck’ when ratepayers subsidize solar and other clean energy,” the letter said. “This will not happen if competition is reduced.”

Expanding Too Fast

The BPU’s community solar initiative is part of Gov. Phil Murphy’s push for New Jersey to reach 100% clean energy and generate 32 GW of solar by 2050. The state had 4.99 GW of installed capacity on Sept. 30, the latest BPU figure available.

The BPU expects to release a straw proposal for a community solar program soon and launch it next year. The two pilot programs held to date — which together awarded 150 projects — each attracted between four and five times as many applicants as were eventually awarded.

Still, the state has been slow in getting community solar projects installed. Only 18 projects have been installed since the state approved the first 45 community solar projects, totaling 75 MW, in 2019, according to BPU records. There are 108 community solar projects in the pipeline.

Lykins said a problem with greatly expanding the program and increasing the number of incentives is that developers could see it as more “lucrative” than other state programs, diverting them from those alternatives, including the Competitive Solar Incentive (CSI) program, which provides the “most economical projects.” The CSI program awards incentives to grid-scale solar projects — those larger than 5 MW in capacity — through a competitive process.

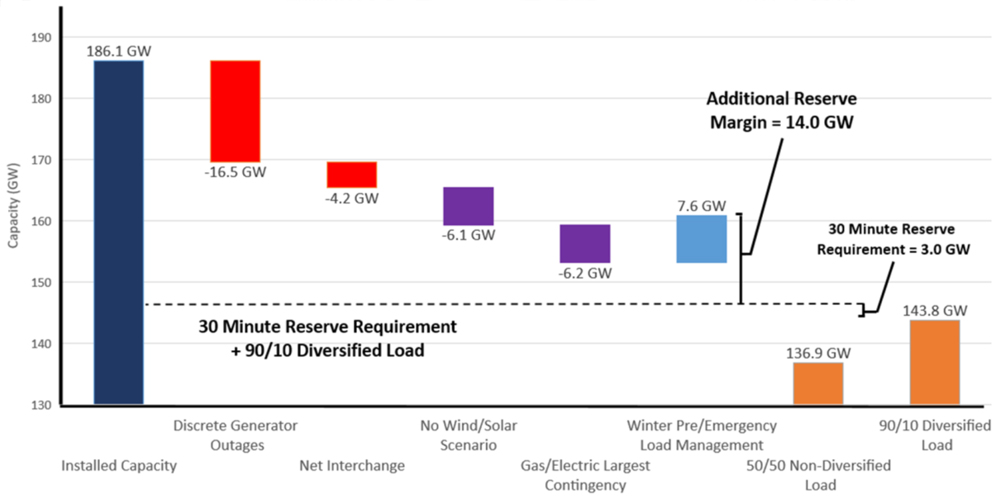

In addition, Chance said, the increased capacity of community solar could put “stress on the distribution grid,” which is already under great strain, with lengthy waits for some utilities to connect solar projects.

“There are certain territories where you cannot sign up even for a small rooftop program” to get connected to the grid, he said. “The concern is raising this cap this high is going to put those same pressures onto the local distribution grid and potentially bring the same problems we’re seeing at PJM here and just bring everything to a screeching halt.” (See Solar Developers: NJ’s Aging Grid Can’t Accept New Projects.)

Moreover, the community solar program to date has accepted only the “very best of the best” projects, he said. The sudden expansion of the program would require it to accept “less quality projects moving forward.”

Chance added that existing community solar projects already struggle to attract subscribers and the difficulty of finding them would limit further program expansion.

Searching For Subscribers

Community solar projects target users who either cannot or do not want to have solar on their roofs but want to support a clean energy initiative. To make the projects work the developer must sign up subscribers, who commit to using the clean energy and in turn receive a credit on their utility bill, reducing the electricity cost by a set percentage.

New Jersey’s program requires 51% of the clean energy to go to subscribers from low- and moderate-income communities, but that requirement has proven challenging to developers, in part, they say, because low-income consumers shy away from providing documents to support their low-income status in their application to become a subscriber.

However, Smith, brushed aside the concern. He told Lykins that the difficulty of finding subscribers would diminish if they were able to “self-certify,” or simply attest to their low-income status without offering proof, as some developers have suggested.

With a “self-certification” system in place, “the program’s going to be filled,” Smith said.

Allison McLeod, policy director for the League of Conservation Voters, agreed that the state should be looking to help disadvantaged consumers. She said community solar so far accounts for only 3% of all residential solar.

“We support using this as an incentive to continue to expand access to low- and moderate-income communities to get the benefits of community solar,” she said.

Yvette Viasus, community solar engagement manager for Solar Landscape of Neptune, New Jersey, the developer of more community solar capacity in the program than any other, said the program could be a good economic driver for the state. She said the program has helped Solar Landscape quadruple its size, and it now has 120 employees and 54 of the 150 projects approved in the program.

“Commercial property owners across the state are eager to host more community solar installations,” she said. “Community solar is ready to go today. Now is the time to increase the capacity of this program.

“It harnesses the potential of one of New Jersey’s most successful shovel-ready clean energy programs and enables us to make progress towards our 100% clean energy future while giving everyone a part to play in fighting climate change,” she said.