WASHINGTON — New ways of paying for transmission could increase interregional transfer capacity and improve reliability, speakers told the Energy Bar Association’s Mid-Year Energy Forum last week.

Nicole Luckey, Invenergy | © RTO Insider LLC

Nicole Luckey, Invenergy | © RTO Insider LLC

Nicole Luckey, senior vice president of regulatory affairs for Invenergy, said her company hopes to make the case for how interregional merchant HVDC can aid reliability during system emergencies at a FERC staff-led workshop Dec. 5 to 6 on setting minimum requirements for interregional transfer capability (AD23-3).

“Merchant transmission can provide these benefits at a significant cost savings when compared to lines paid entirely on a traditional cost-of-service basis,” she said. “Of course, the majority of the time, a merchant line is going to be providing service to its customers. But if properly incorporated into commercial agreements, that service could be interrupted to provide emergency energy and capacity to keep the lights on.

“Transmission’s value during extreme weather events is being significantly undervalued, and … policy to encourage merchant transmission — which can deliver these benefits to the grid, and potentially avoid complicated cost allocation arguments that I think have really stymied the deployment of transmission in this country — has been completely overlooked,” she said. “Worse, because merchant transmission is treated inconsistently across the country, it creates a disincentive to deploying it interregionally.”

Michael Skelly, Grid United | © RTO Insider LLC

Michael Skelly, Grid United | © RTO Insider LLC

Michael Skelly, founder and CEO of Grid United, which is seeking to build long-distance, interregional transmission, also called for new models for funding transmission, during an EBA panel discussion Oct. 11.

“I think there’s this notion that we’re either going to build a line and it’s going to get cost allocated toward everybody, or it’s not going to get built at all. … But there are other models out there,” he said, citing batteries, which can collect revenue for providing grid services such as frequency regulation but also generate revenues through energy markets.

Skelly also pointed to the U.K.’s proposal to construct transmission to France, under which a developer would receive a “floor” return of 3 to 4% with the ability to earn up to 15% through markets. Profits above the 15% cap would be returned to ratepayers who help finance the project.

Under such a model, “transmission lines start to look a little bit like generators,” he said. “And we’ve actually had pretty good luck mobilizing capital around investment in generation.”

By reducing the guaranteed return to 3 to 4% from 7 to 8%, “your revenue requirements go down like 40%,” he said. “You could save a lot of money if other parties take some of these risks.”

2,000 MW

David Kelley, SPP | © RTO Insider LLC

David Kelley, SPP | © RTO Insider LLC

David Kelley, director of seams and tariff services for SPP, noted that the U.S. currently has little more than 2,000 MW of transfer capability among its three interconnections: 1,270 MW from the Western to Eastern Interconnection, and 800 MW between SPP and ERCOT.

“Think about the scale of the demand in this country. And we really only have the ability to share a little over 2,000 MW from the East Coast to the West or vice versa,” Kelley said. “I really think interregional transmission can certainly play a role in helping us introduce more operational flexibility. And HVDC, in particular, I think plays a really key role as we’re talking about transferring between the interconnections.”

The importance of transfer capacity was tragically illustrated during Winter Storm Uri in February 2021, when ERCOT and SPP were forced to shed load, leading to more than 200 deaths in Texas.

“Without a doubt, this was the most challenging operational event in SPP’s history,” said Kelley, who noted it was the first time SPP had to direct load sheds in its history. “That was a very sobering moment for our organization. And I know we fared better than others did. But that was absolutely a wake-up call for us.”

During the height of the storm, SPP was importing as much as 6,000 MW. David Souder, PJM’s executive director of system planning, who also spoke on the panel, said the RTO exported as much as 19,000 MW to its West while importing 3,000 MW from the North.

HVDC’s Impact: Location, Location, Location

Moderator David Schwartz, of Latham & Watkins, asked Kelley how much of a difference HVDC transmission could have made to SPP during Uri.

Kelley said it would depend on the HVDC line’s sink location relative to SPP’s AC transmission.

During the storm “we ran into limitations within the SPP footprint … moving massive amounts of energy in ways that was never planned to be moved within the SPP region before,” he said.

“You may have a 3,000-MW HVDC line that’s perhaps dumping power at a specific location within the footprint. So can you receive it there? And then can you move it to where it needs to go within the region?

“At the time, we were shaking couch cushions trying to find every kilowatt we could find in order to keep the lights on. So would we have loved to have had another 3,000 to 4,000 MW? Absolutely. But it would have to be at the right spot, I think, in order to be effective.”

Dunkelflaute

Kelley said SPP recently increased its planning reserve margin to 15% from 12% because of concerns about the variability of its wind power. Although the RTO has more than 33 GW of nameplate wind capacity — and in March was serving 90% of its load with renewables at times — “we still have periods of time where we have less than a gigawatt of wind capacity generating within our footprint,” he said.

Skelly noted that the Germans have a phrase for the fear of having inadequate sun or wind energy: dunkelflaute, or “a dark lull.”

“This is a real challenge in this energy transition that so many of us are trying to try to figure out,” said Skelly. “One way to do that is to connect the grids, because we have a whole continent to work with here. We don’t have just, you know, a few hundred miles.

Skelly said it’s a bigger problem for SPP than MISO. “MISO is basically oriented East-West,” he said. “As Dale Osborn, a legendary MISO planner always points out, when you have wind fronts move across the country, if you have enough grid, you can integrate those along the way.”

The Easy Part

Kelley said the obstacle to increasing interregional capacity is not technical.

“The engineering part of this is pretty easy. Getting everybody to agree on what the problem is to be solved — and then to how do you pay for that — those are the hard parts,” he said. “You can get a group of engineers in a room to run a study [and] we could probably design a national grid for you in less than a year. And I’m not kidding about that. That’s how easy it is, if everybody agreed on what the national grid was supposed to do, and who was going to pay for it.”

Invenergy’s Luckey said one problem is that RTO voting structures “gives incumbent transmission owners a lot of power.”

Incumbents were unhappy that FERC Order 1000 called for interregional projects to be competitively bid. “I don’t want to sit here and say that’s the only reason these projects haven’t been planned. But it certainly doesn’t help that incumbent TOs know they’re going to have to compete,” she said. “They’d really rather build stuff they know they’re not going to have to compete to build.”

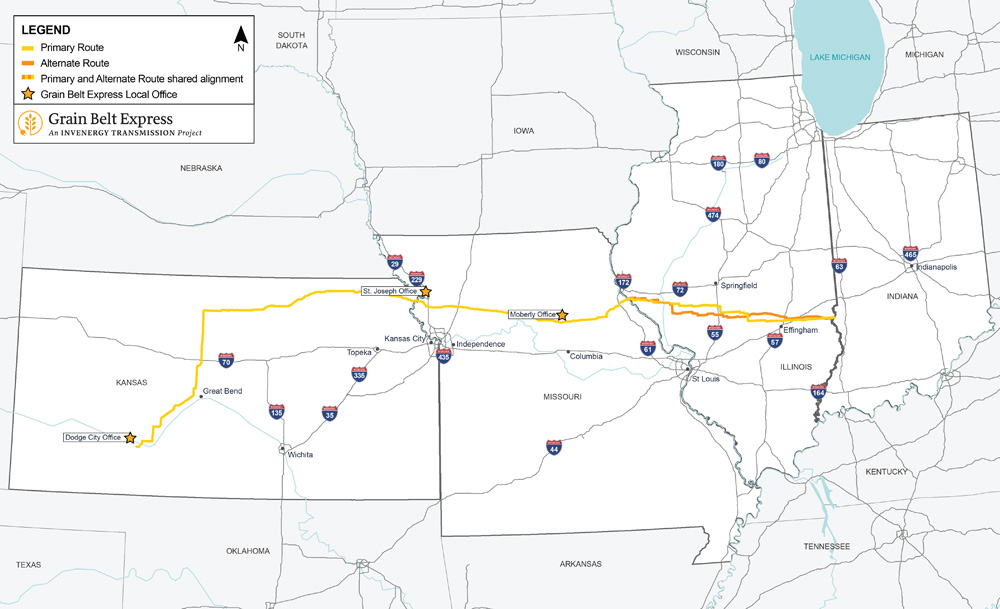

Another problem is how RTOs perceive merchant transmission, such as Invenergy’s proposed Grain Belt Express, an 800-mile, 5-GW HVDC line that would connect four balancing authorities: SPP, MISO, PJM and Associated Electric Cooperative Inc., which serves 51 distribution cooperatives in Missouri, Iowa and Oklahoma.

Invenergy envisions its proposed Grain Belt Express as “the reliability backbone of the Midwest” Designed to deliver wind and solar power from western Kansas to customers in Missouri, Illinois and beyond, it could reverse flows during system emergencies. | Invenergy

Invenergy envisions its proposed Grain Belt Express as “the reliability backbone of the Midwest” Designed to deliver wind and solar power from western Kansas to customers in Missouri, Illinois and beyond, it could reverse flows during system emergencies. | Invenergy

The project, which the company envisions as “the reliability backbone of the Midwest,” is designed to deliver wind and solar power from western Kansas to customers in Missouri, Illinois and beyond. “But during system emergencies, if we have contractual agreements in place with our customers, we could reverse flow on that line,” Luckey said.

In MISO, Luckey said, “we’re triggering hundreds of millions of dollars in network upgrades, simply to interconnect our merchant transmission project, which by the way, will provide benefits to that region. So not only are we paying to upgrade the system to move our energy around — to make sure that it’s deliverable. But now we’re providing a benefit to the system, potentially based on the multidirectional ability [of] an HVDC line. But there’s really no way for the grid operator to evaluate what the benefit is to their system right now. They see us as more of a problem that needs to be solved rather than as an asset that can benefit them.

“That’s not necessarily their fault, right? That’s just the way the system is sort of set up for merchant transmission today. And I think it’s something that needs to be changed, because you don’t have that one entity that’s looking at this project and saying, ‘How can this benefit these two regions?’”