WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court’s ruling barring use of “generation shifting” to reduce greenhouse gas emissions will discourage executive agencies from ambitious rulemakings but is not yet a “nuclear bomb” that will cripple regulation, attorneys told the Energy Bar Association’s Mid-Year Energy Forum Wednesday.

The court ruled June 30 that the EPA failed to provide “clear congressional authorization” for the Clean Power Plan, which would have compelled generation shifting to reduce carbon emissions from coal-fired power plants (West Va. v. EPA). The court cited the “major questions doctrine,” which it said was necessary to address “a particular and recurring problem: agencies asserting highly consequential power beyond what Congress could reasonably be understood to have granted.” (See Supreme Court Rejects EPA Generation Shifting.)

Proposed by the EPA under the Obama administration, the CPP was withdrawn by the Trump administration — replaced by the Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) rule, which was in turn withdrawn by the Biden administration.

Crippling?

Stinson partner Harvey Reiter, who moderated EBA’s morning general session Wednesday, has written that the ruling is “a potential nuclear bomb that can be aimed not merely at a particular rule, but at crippling an agency’s ability to regulate at all.”

Harvey Reiter, Stinson | © RTO Insider LLC

Harvey Reiter, Stinson | © RTO Insider LLCReiter’s fellow panelists had a less apocalyptic view.

Elizabeth “Ellie” Boucher Dawson, counsel with Crowell & Moring, said she didn’t agree with Reiter’s dire prediction.

“Not yet, anyway,” said Boucher Dawson, who wrote an amicus brief on the case for the Edison Electric Institute. “For me, it’s very significant that Justice [Neil] Gorsuch only wrote a concurrence and not the majority opinion.”

Gorsuch pushed for a more extreme interpretation of the major questions doctrine as a limit on congressional delegations of policymaking to agencies. But only Justice Samuel Alito joined his argument.

Aram Gavoor, a lecturer at George Washington University Law School, said the court’s decision “did not substantially change administrative law.

“I think it could, like Ellie described, eventually be something that’s quite serious. But the court will have to press the button again — a few more times — to really reinforce it.”

Matthew Leopold, a partner in Hunton Andrews Kurth, said the ruling set “a speed limit on the regulatory highway that agencies should not exceed without the risk of their rules getting struck down.

“I think it will hold the agencies back, but the regulatory administrative process is alive and well,” he said.

No Limits on ‘Major Questions’?

Although the court’s ruling said the major questions doctrine would only apply in “extraordinary circumstances,” Reiter noted that the court cited it in three rulings in its last term, involving the Food and Drug Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. He said the issue also was raised in more than 100 circuit court and district court challenges since 2020.

Matthew Leopold, Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP | © RTO Insider LLC

Matthew Leopold, Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP | © RTO Insider LLCAram said the West Virginia ruling resulted in a “mushy” standard that will encourage many litigants to raise it. “Part of this might also be [that] for the court to have gotten the majority for West Virginia v. EPA, maybe it needed to be a little bit broad,” he said, adding that future rulings could result in “the metes and boundaries of what major questions really means.’”

“The nature of lawyers is to raise any argument that might get traction, so I think people will overuse it,” Leopold added. “… But I think that the extent to which it’s raised — and then more importantly, the extent to which courts really lean into it and start utilizing it — has a direct relationship to how much federal agencies … are overreaching their long-held authority or positions.”

Samuel Backfield, legal counsel to FERC Commissioner Mark Christie, said the agency expects to see the argument raised in the future.

“I think that what’s going to happen next is that there’s going to be a process of refinement of the doctrine. … Right now, what we have essentially are indicia; we don’t have a firm test,” he said. “It’s not meaningless that we have this indicia condition instead of a firm test. I mean, I’m sort of reminded of Edmund Burke’s comment that no man can draw a stroke between night and day, and yet darkness and light are reasonably distinguishable.”

Reiter suggested the ruling could prompt “forum shopping” because appeals of most agency decisions go first to one of the 94 district courts rather than a circuit court of appeals, as with FERC challenges.

“I think there’s gonna be a substantial amount of it,” agreed Aram. “… It’s also going to cause a lot of struggling with the circuit courts as to what does this mean for Chevron deference” — which requires courts to defer to a federal agency’s interpretation of an ambiguous law that Congress assigned to the agency to administer.

Impact on Prior Rulemakings

Elizabeth Boucher Dawson, Crowell & Moring | © RTO Insider LLC

Elizabeth Boucher Dawson, Crowell & Moring | © RTO Insider LLCBoucher Dawson said she was relieved that the court did not “reach back in time” to undo its previous rulings, such as Massachusetts v. EPA, in which it ruled greenhouse gases were air pollutants and could be regulated by EPA under the Clean Air Act.

Reiter questioned whether FERC’s prior rulemakings could be in jeopardy as a result of the narrowing of the Chevron doctrine. He noted the commission cited the Federal Power Act as its authority for regulating demand response, “which wasn’t even a thing in 1935,” when the FPA was enacted. Some commenters raised the major questions doctrine in FERC’s current transmission planning Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (RM21-17), he added.

FERC’s Backfield said the challenges could result in unpredictable outcomes. “There are courts of appeals and panels that would rule differently, I think, on certain of the cases,” he said.

Backfield declined to opine on whether any of the commission’s major rulemakings would survive scrutiny under major questions. “But … other than demand response, they’ve mostly been around for quite a while. And there is at least a rationale that these do go to the fundamental central regulatory duty of the FERC, which is to ensure just and reasonable rates.”

“I don’t think that the Supreme Court — at least the majority of the justices — would coalesce around an opinion that picks on old scabs,” said Gavoor. “I think if we anachronistically applied West Virginia v. EPA to some of these older actions by the agency they’d be at risk. But I don’t think they’re at risk right now. I think recent actions and ones that are in the future are likely to be at risk.”

Impact on Future Regulations

Leopold noted that the Securities and Exchange Commission recently reopened comment on a portion of its proposed greenhouse gas rulemaking, a suggestion that it sees vulnerability to a major questions challenge.

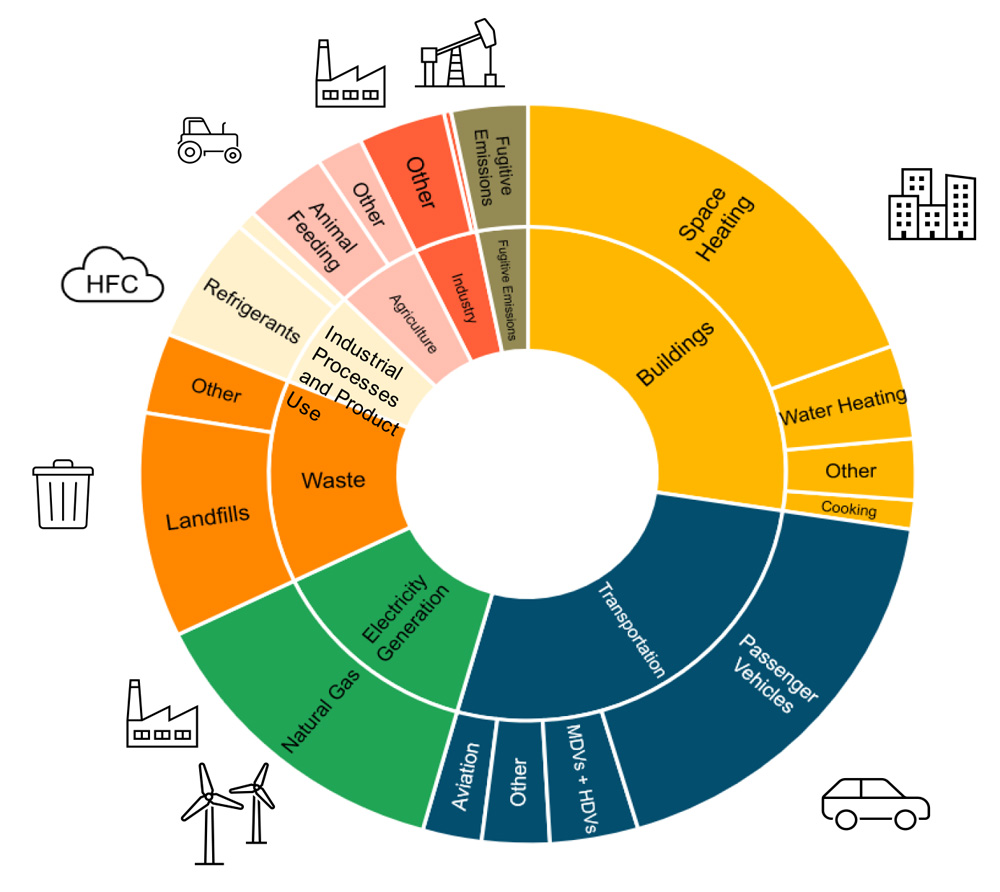

“The SEC has been around since the Depression, and they’ve never really gotten in the environmental game. But they’re all of a sudden saying you have to disclose your climate risks. You have to disclose your greenhouse gas emissions — not just your direct emissions, but your scope one, two, and three [emissions] — including three, and no one even knows how to calculate that,” he said.

Aram Gavoor, George Washington University Law School | © RTO Insider LLC

Aram Gavoor, George Washington University Law School | © RTO Insider LLCLeopold said the ruling has resulted in a “burden shift.”

“If it’s a major question, the burden is now on the agency to say that they have the authority, rather on the petitioner who was challenging the agency rule to say … that that application of their authority was not a reasonable interpretation. So that’s a major change.”

He said the ruling also shifts the burden to Congress, which will be required to demonstrate “political will” to pass new legislation.

Aram said he expects “more incrementalist regulation so as not to cross this tripwire of major questions.

“So, I think it is going to require a change in tactics and strategy. I think it will result in some tension with the White House, because the White House absolutely loves to politicize any sort of policy. … It’s going to have to be much more strategic and cautious. And the [legislation] shops are going to have to be far more engaged.”

Leopold, a former Justice Department attorney, said if he were still advising federal agencies, “I would be telling them very specifically, do not characterize this in the press as ‘major, transformative, earth shattering, we’re going to save the planet’ unless you really do have clear authority to do so.

“Those types of grandiose statements [are] going to raise the hairs on the back of the neck of judges who care about [the] major questions [doctrine].”

What’s Possible in GHG Rules?

With new Clean Air Act amendments unlikely, it’s unclear what GHG regulations EPA could approve that would pass muster. The administration told the court in oral arguments in February that it planned to issue a replacement for the CPP by the end of this year.

Would carbon capture pass the court’s scrutiny, as Justice Kagan suggested in her dissent?

“I think that’s possible because that that would be a technology applied at the source, conceivably, if you had a way to sequester the carbon there or nearby,” said Leopold. “If you’re having to pipe it miles way to another reservoir, that could raise questions.”

Leopold said Kagan, however, ignored the Clean Air Act’s requirement that the “best system of emission reduction” also be “adequately demonstrated.”

“We know from attempts at the Kemper plant in Mississippi that carbon capture and sequestration for coal fired plants still has a lot of hurdles — financial hurdles, in particular.”