WASHINGTON — Energy storage, along with other distributed energy resources, are changing the way electricity markets and the grid are planned, structured and operated, and the new tax incentives for standalone storage in the Inflation Reduction Act will accelerate the pace and urgency of the transformation ahead.

The impact of the law and the growing presence of storage as a core technology for grid reliability and decarbonization were the focus of a panel at the American Council for Renewable Energy’s Grid Forum on Thursday. In his opening remarks, Carl Fleming, a partner at McDermott Will & Emery, reported that the IRA is driving deals at his law firm, even before the Internal Revenue Service issues guidance on the new law’s tax credits.

“We’ve seen a number of deals — the first two tax equity … deals, the first two energy community deals and the first two transferability deals,” Fleming said, referring to specific provisions in the law that provide bonus credits and expand the entities that can receive credits.

New figures from BloombergNEF are predicting global storage capacity of 411 GW by 2030, a 15-fold increase from the 27 GW online at the end of 2021, he said — a forecast driven in part by the IRA.

Ann Coultas, Enel North America | © RTO Insider LLC

Ann Coultas, Enel North America | © RTO Insider LLC

Ann Coultas, regulatory affairs director at Enel North America, said her renewable energy development company, like many others, is still “digesting everything in the legislation and figuring everything out. I would say we are very familiar with working across a variety of platforms, whether it’s wholesale energy markets, whether it’s microgrids; and one of the exciting things about this legislation is that it has incentives for all types of applications.”

Similarly, for Gabe Murtaugh, storage sector manager at CAISO, the law provides more options for leveraging the 5,000 MW of storage that will be coming onto the California grid in the next two years, doubling the close to 5,000 MW now online.

Existing tax credits for storage are narrowly drawn, Murtaugh said. To qualify, a project had to be co-located with and only charge from solar or another renewable energy source.

“If you as a grid operator need those resources to charge during the middle of the night, when there is no solar [or when] there’s no wind, you can’t do that under the current rules,” he said. “The new rules are going to allow a lot more flexibility for these resources to participate maximally in the market.

“Those are the kinds of rules and the kinds of incentives we need in place … to build the new renewable resources and the resources that are going to make a sustainable resource portfolio mix possible, but don’t necessarily restrict how those resources are going to work in the market,” Murtaugh said.

Nidhi Thakar, Form Energy | © RTO Insider LLC

Nidhi Thakar, Form Energy | © RTO Insider LLC

The IRA will also help startup Form Energy bring its multiday, iron, air and water-based long-duration storage technology to market faster, said Nidhi Thakar, vice president of policy and regulatory. “It helps companies like us who are preproduction and prerevenue to commercialize faster, to put steel in the ground faster and to start producing our batteries.”

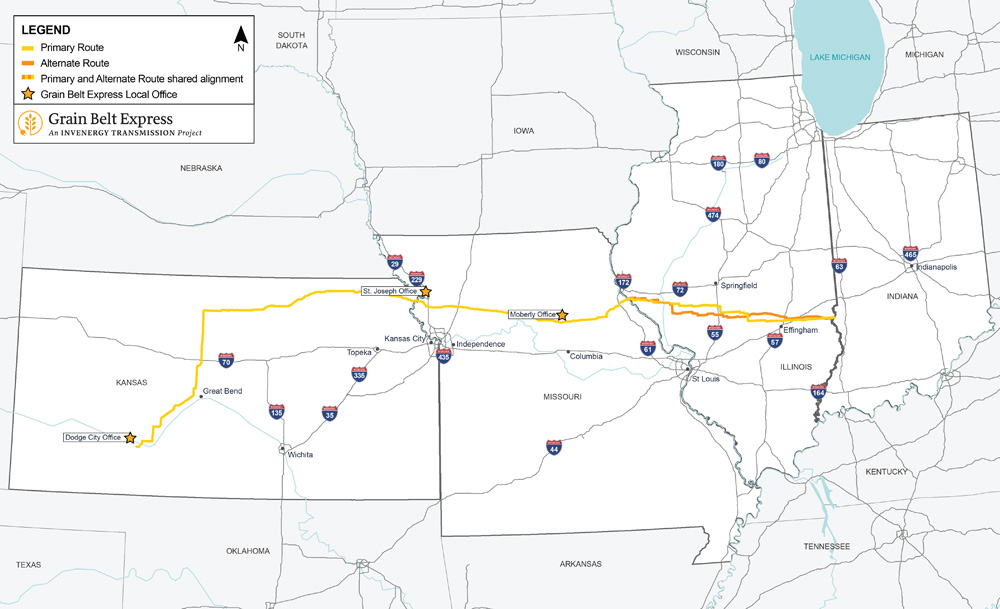

Form is in the process of selecting a site, east of the Mississippi River, for its first factory, which will be able to produce 500 MW of its 100-hour batteries, Thakar said. However, while lauding the “unprecedented” clean energy investments in the IRA and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Thakar also pointed to the gaps in the laws, including the need for permitting reform and tax incentives to support new transmission.

“We can’t take full benefit of what’s in the IRA for clean technologies” without addressing these issues, she said.

‘Shallow’ Markets and Marginal Pricing

The panel also tackled the uneven pace of storage integration on transmission and distribution systems and its deployment as a grid asset, as some utilities, regulators and grid operators continue to argue that the technology is not sufficiently mature or cost competitive.

In California, the leading storage market, four-hour duration lithium-ion battery storage is now the standard, Murtaugh said. But longer-duration technology will be needed for the days or weeks when renewables aren’t available, because of the increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events driven by climate change.

A core challenge in California and other markets is the need to develop market structures that incentivize the deployment of storage and appropriately compensate the specific attributes of the technology. Traditional marginal pricing, effective for fossil fuel generation, doesn’t mean much for storage developers, Murtaugh said. “They don’t care so much about instantaneous prices; what they care about is the price that they can buy energy at and the price they can sell energy at,” he said.

Markets based on thermal generation and spinning and non-spinning reserves are not designed for battery growth, Coultas agreed. They don’t offer “the right products to attract a battery,” she said.

Enel has had a lot of success with batteries in Texas, where ERCOT has “defined products in ways that suit batteries really well. So, there are products where you must respond within 20 cycles; you must respond within a matter of seconds or milliseconds. Products like that in a market [are] going to attract batteries.”

ERCOT’s battery-friendly products, however, are offset by the grid operator’s “shallow” markets, Coultas said, meaning that the energy needed is relatively small. “To attract more batteries, markets need to be really thinking about creating the right level of ancillary services,” she said.

Further, no one has completely cracked the pricing issue yet, Coultas said, though she pointed to ERCOT and CAISO as models of progress.

Murtaugh said one possible solution is to replace LMP with “something where we pay a fixed amount to a storage resource when we’re charging that storage up, and the ISO has sort of a call option to be able to discharge that resource any time we want to.”

Coultas offered yet another possibility — technology-neutral dispatchable energy credits, similar to renewable energy credits, for resources “that have attributes guaranteeing dispatch,” she said. At the same time, she cautioned, “There are values [of storage] that will just never be compensated in a multistate ISO because they don’t have the power to do that; for example, clean peak. I don’t think in a multistate ISO we’re ever going to a see a product that pays batteries for clean peak.”

In CAISO, Murtaugh and others are working on changing California’s resource adequacy programs, now based on peak demand, “to a new paradigm where we’re going to be looking at making sure we have enough energy overall 24 hours a day, as well as actual generation during each hour of the day and for charging resources earlier in the day,” he said.

New Tools

Thakar believes that long-duration technologies, like Form’s, could provide targeted, “microfitted” solutions for a range of grid challenges, “whether it’s for use on a consistent basis or as support to central service providers or other critical communities that are stuck in some of these difficult load pockets and experience a lot of grid instability,” she said.

But, she said, no markets, not even California’s, have created market valuation or compensation structures for the “innovative resources that are going to be coming online in the next couple of years.”

Part of the problem, Thakar said, is that the focus on federal implementation of the IRA has left a blind spot around implementation of the law by state utility commissions.

State-level integrated resource plans have relatively short time frames — two or three years — for procuring clean energy resources, she said. “How does that hamstring the general ability to take advantage of the 10-year window we have for benefits from the IRA now? … We need to be thinking about what kind of tools can help state regulators really fully capture the overall benefits of IRA for customers.”

Form has built its own modeling tool that “focuses on a 365-day evaluation, using a model that looks at that entire yearlong snapshot. It also looks at multiple weather years,” she said.

Murtaugh said he and CAISO’s operations team have also spent the last few years “building a whole suite of tools that we never even contemplated having before because we were never worried about storage state of charge and thinking about energy we could potentially dispatch later.”

“We’re enhancing all of our markets and the modeling we do for storage resources to accommodate resources that can charge and discharge, resources that have a minimum and maximum state of charge, so that our market can optimize those resources alongside all the other resources. There are a lot of unique operating characteristics for storage resources,” he said.

“In the next five to 10 years, I think a lot of ISOs are going to be seriously thinking about their market constructs,” Murtaugh said. “I think we’re going to see some pretty radical changes come after that.”