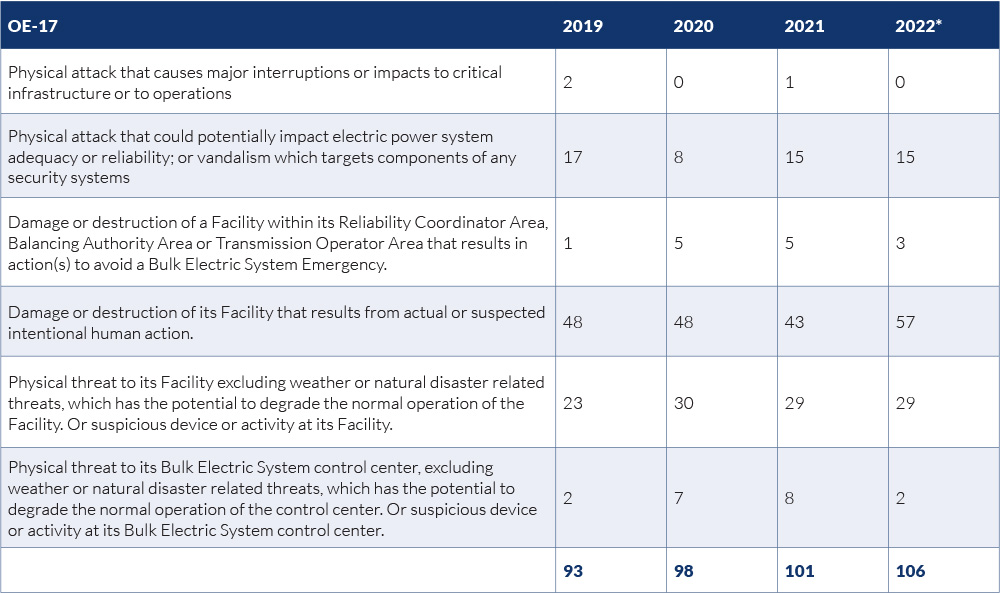

New York City is on the verge of implementing the nation’s first traffic congestion pricing scheme, titled the Central Business District Tolling Program (CBDTP), which will seek to generate revenue and reduce pollution across the city.

MTA’s Central Business District Tolling Program Area | MTA

MTA’s Central Business District Tolling Program Area | MTA

The CBDTP would electronically charge motorists up to $35 when entering Manhattan below 60th Street to reduce traffic while raising revenue to fund improvements to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) subway and bus systems.

Passed by the New York State Legislature in 2019, the plan was originally slated to be implemented in 2021, but lack of federal environmental guidance, the COVID-19 pandemic and a changing governorship because of political scandals delayed the project until at least 2024.

The MTA, which has been slow to recover from the unprecedented drop in ridership during the pandemic, estimates that the CBDTP will generate $1 billion annually.

Despite potential economic benefits and grassroots pressure to act on climate change, there has been fierce opposition to the plan, specifically around the proposed costs and the shifting of pollution to the city’s outer boroughs.

History & Details

A congestion pricing scheme for the city was first proposed in 2007 as a disincentivizing fee that would reduce traffic and generate revenue but was only formally approved in the state’s 2019 budget.

The legislation was initially light on details but created exemptions for emergency vehicles, residents who reside inside the tolled zone but earn less than $60,000, and disabled persons.

One critical detail that was known about that the CBDTP was that it would operate through electronic sensors connected to the E-ZPass system.

Although officials have not settled on a fee scale, authorities have stated that E-ZPass holders entering the CBD at peak times would pay between $9 and $23, while those without one and pay the toll by mail can expect to spend as much as $35 during peak times. Discounts would be enabled during off-peak and overnight periods.

The CBDTP’s biggest gaps are around how different types of vehicles, particularly delivery trucks, private taxi services such as Uber and the famous yellow taxis, would pay these tolls. Critics have also complained about the lack of distinction being made between commercial and noncommercial vehicles.

Some proposals that may allay these concerns, but are still under consideration, include setting fee caps on vehicles that have entered the CBD more than once, creating further exemptions for certain classes of passenger vehicles, or even having the MTA’s own buses pay the toll.

Despite these concerns, supporters are delighted by the prospect that the city may implement a decades-long quest to unclog its jammed streets. They and the MTA have pointed to Stockholm, London and Singapore as examples of how congestion pricing schemes not only reduced traffic but also reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

According to the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), Stockholm’s congestion program resulted in a 25% reduction in congestion, a nearly 15% reduction in emissions and at least a 6% increase in use of public transport, while London’s program led to a 20% drop in emissions, a 30% increase in average vehicle speed and a 25% drop in traffic.

The momentum behind the CBDTP briefly stalled in anticipation of an environmental review that needed to be conducted by both the federal government and state agencies but was delayed during the Trump administration.

Environmental Assessment

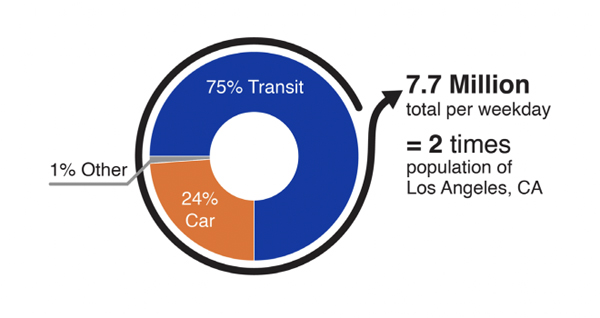

The FHWA’s long-awaited environmental assessment (EA), released Aug. 10, evaluated the effects of the CBDTP across seven different tolling scenarios.

The EA found that all scenarios would reduce traffic into Manhattan by as much as 20% for personal vehicles and up to 80% for trucks, though this could lead to a 2.6% increase in trucks driving outside the borough, including through North Jersey.

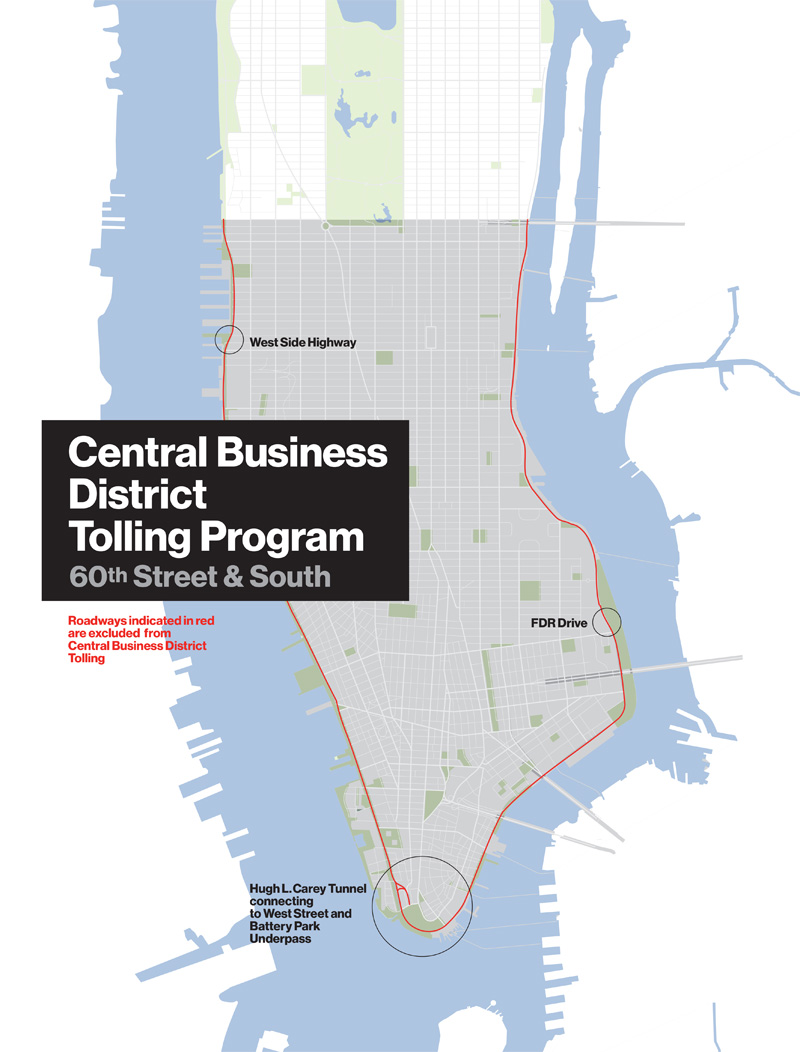

Total Number of People Entering Manhattan CBD in 2019 | NYMTC Hub Bound Travel Data Report

Total Number of People Entering Manhattan CBD in 2019 | NYMTC Hub Bound Travel Data Report

The report promisingly found evidence that New Yorkers would ditch their personal vehicles for public transportation and that certain scenarios resulted in reductions of as much as 12% of pollution in the CBD.

The EA was required because tolls would be collected on federally funded roads, and a study needed to examine any impacts that the program would have on disadvantaged communities.

In this regard, the report found that certain environmental justice communities could experience reductions in traffic, though these would be offset by traffic increases in areas where toll-dodgers shifted their driving.

The EA’s findings gave some congestion pricing supporters pause as they feared that localized concerns would narrow the CBDTP, which they believe is critical to reducing the city’s overall pollution, tackling the climate crisis and providing funding to a mass transit system still recovering from the pandemic.

The EA did in fact create considerable public backlash, particularly from those located in the South Bronx, Staten Island, Nassau County and Bergen County, N.J., who would feel the brunt of both the environmental and economic consequences from the CBDTP.

In fact, the backlash was so strong that the EA’s public commenting period was extended until Sept. 23 to allow more time for public input after being initially slated to conclude on Sept. 9.

Detractors & Supporters

The debate rages on, and New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy (D) was the latest contributor.

Murphy said he was opposed to the CBDTP because the recent EA was too “long and complex.” He also said residents had little time to digest its findings nor had any involvement in the planning process, yet they would suffer from the costs without receiving “any direct benefit from the revenues.”

The governor, however, remains supportive of a congestion pricing scheme intended to reduce traffic and emissions. But he alleged that the CBDTP’s primary goal is “revenue production.”

Similarly, New York Mayor Eric Adams (D) supports congestion pricing, but he recently said that the city had “very little input” on the program, and it required more exemptions for disadvantaged and disabled citizens, who he claims will struggle to afford the tolls.

Opposition has forcefully come from U.S. Rep. Nicole Malliotakis (R), who represents New York’s 11th congressional district covering Staten Island and Southern Brooklyn. She said at one recent public hearing that the CBDTP “is being jammed down the throats of the people.”

These sentiments were echoed by U.S. Rep. Josh Gottheimer (D), who represents New Jersey’s 5th congressional district covering parts of North Jersey, including much of Bergen County. Gottheimer said in a hearing that the plan will “drain our families’ pocketbooks” while doing “nothing to actually help the environment or ease congestion.”

Another House Democrat, Ritchie Torres, who represents New York’s 15th congressional district covering the South Bronx, said in a statement that he is concerned about “any plan that threatens to intensify diesel truck traffic on the Cross Bronx Expressway” because it “would raise serious concerns about public health and racial equity.”

Despite fierce opposition, the CBDTP still has supporters.

Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso (D) recently said at a hearing that “for our city to continue to function, we must get people out of their cars and back onto reliable public transportation.”

Meanwhile, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul has remained supportive of the CBDTP, having said during the Democratic gubernatorial primaries earlier this year that she “supports congestion pricing 100%” and has shown little sign of working against its implementation.

Additionally, many participants during the public commenting period expressed support for the plan because of the potential reduction in traffic, increased speed of public transport, improved air quality in many parts of the city and reduced pollution.

Supporters also countered their detractors by claiming that the amount of people who will shift to mass transit, as well as the upgrades to these systems, will offset localized concerns.

Outlook

Without significant pushback, however, the CBDTP is poised to be approved in mid-2023 and implemented by early-2024.

With the recent completion of the FHWA’s review and the conclusion of the public commenting period, the next steps will be for MTA to share the public’s feedback with the FHWA, which is then expected make a formal decision on the EA in January 2023.

If the FHWA’s final review finds no significant impact from the CBDTP stemming from the public comments, a six-person Traffic Mobility Review Board (TMRB) will finalize toll rates and detail how a credit system will be implemented.

Should the FHWA find any issues, however, it may require a more thorough environmental impact statement, which is what some critics, such as Murphy, have been requesting. Ultimately, the final arrangement will be voted on by MTA board members.