Oregon’s adoption of California’s Advanced Clean Cars II (ACC II) rules could cost automakers up to $3 billion to comply with the regulations but provide the Pacific Northwest state about $5.8 billion in economic benefits by 2040, according to the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ).

The new rules would also support the state’s efforts to improve racial equity by reducing pollution along transportation corridors that often run through low-income areas home to a disproportionate number of people of color, the department says.

The assessments were included in the DEQ’s draft fiscal and racial equity impact statements, a requirement of its process to review and adopt the ACC II rules.

The California Air Resources Board (CARB) last month approved ACC II to replace the Golden State’s existing vehicle emissions standards, starting with model year 2026. The new rules ban the sale of new gasoline-powered cars in California in 2035 and include a stricter low-emission vehicle (LEV) component for any such cars sold before then. (See Calif. Adopts Rule Banning Gas-powered Car Sales in 2035.)

Oregon is one of 17 states that follow California’s strict tailpipe emissions standards rather than the U.S. EPA’s looser ones. The DEQ has been moving quickly to adopt ACC II by 2026. (See Oregon Moving Quickly to Adopt Advanced Clean Cars II Rules.)

In developing the ACC II fiscal impact statement, the DEQ relied heavily on research already performed by CARB to ascertain the financial effects of the new rules, Rachel Sakata, senior air quality planner, said Tuesday during an online meeting of the state’s ACC II Advisory Committee. The meeting was intended to gather feedback from the committee and the public on the potential impact of the rules — especially on small businesses — before the DEQ issues a notice of proposed rulemaking next week.

Sakata said the $3 billion in impacts to automakers represents Oregon’s estimated share of the costs the companies will take on to convert their production to zero-emission vehicles and LEVs and market them to consumers. The DEQ’s figure is based on CARB’s finding that the impact of adopting the rules for California alone would cost car manufacturers $30 billion.

“The costs associated with this proposed rulemaking are going to be costs incurred by the manufacturers to produce and deliver certain percentages of zero-emission vehicles for each model year” for Oregon, starting with a 35% ZEV requirement for 2026, Sakata said.

The DEQ draft impact statement points out that cost to comply in Oregon could actually be less than $3 billion because of the economies of scale resulting from compliance in California.

“I think Ford alone has committed to investing $50 billion before 2026 on our EV plan, and I know where that’s just Ford; the other companies are in similar spots,” said Advisory Committee member Steve Henderson, director of vehicle regulatory strategy and planning at Ford. “So there’s a tremendous amount of investment being targeted for this, and that’s a good thing; that’s going to make this happen — but it’s a lot more than $3 billion.”

“You’re thinking nationwide, right?” Sakata asked.

“These are the costs of development; these aren’t the costs of selling,” Henderson replied. “I’m not in a position to say what our costs of selling the EVs will be compared to the [internal combustion engine cars], but that’s the amount that we’re investing so that we can produce these vehicles.”

Sakata said the DEQ acknowledged that the new rules will incur direct costs for 17 auto manufacturers, but she also noted that California is already seeing declining costs for EV batteries.

“We recognize that the costs to manufacturers will be high per vehicle, particularly in the early years of this regulation, but are expected to decrease over time by 2035,” she said.

Health Benefits

The fiscal impact statement assumes no direct costs to consumers from adopting ACC II but notes the potential for indirect costs in the form of higher prices for EVs and the need to install home chargers. Still, those costs should be outweighed by $675 million in indirect net benefits resulting from the expected lower overall cost of ownership for EVs, largely from lower maintenance costs and reduced fuel expenses, the DEQ found.

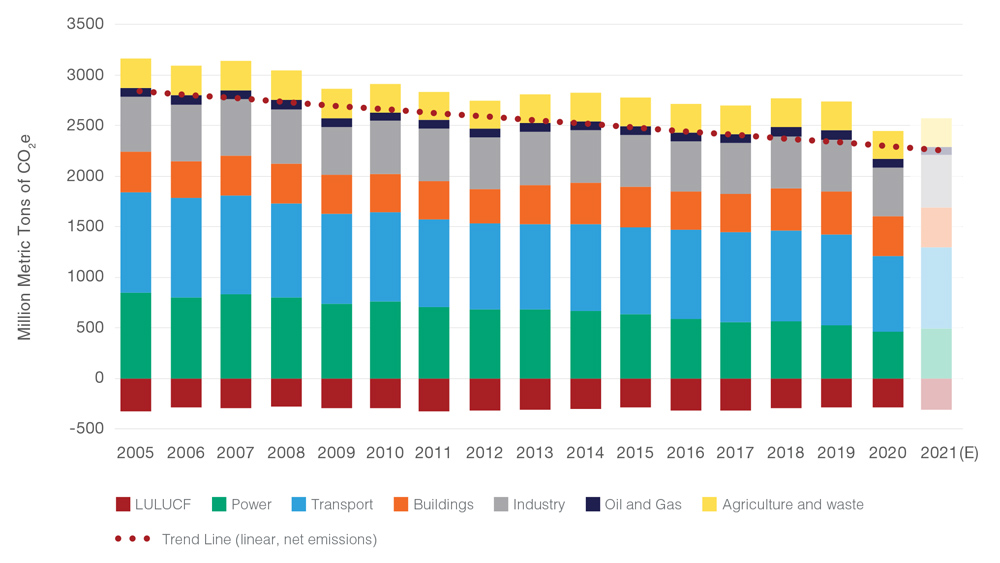

But the department foresees a much larger pool of net benefits — more than $5 billion — based on savings stemming from the reduced emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants. Based on its own estimates and those of the Northeast States for Coordinated Air Use Management (NESCAUM), the DEQ expects the ACC II rule will reduce Oregon’s GHG emissions by 48 to 54.1 MMT per year by 2040.

“A recent analysis conducted by DEQ for the [Oregon Clean Fuels Program] Expansion 2022 Rulemaking indicates that transitioning to lower-carbon transportation fuels through 2035 provides significant health benefits to Oregonians, in the range of $90 million per year of avoided health costs. Much of this can be attributed to reduction in particulate emissions due to electrification,” the impact statement says.

The DEQ cited pollution reduction as a major benefit in its impact statement on racial equity, which state law requires must be a primary consideration in all new regulations.

“The pollution and public health impacts from on-road vehicle emissions are significant in many overburdened and underserved communities. Communities that are adjacent to or near transportation facilities and corridors are disproportionately impacted by those emissions and are traditionally lower-income and have a higher percentage of Black, indigenous and other peoples of color residents,” the statement says.

Sakata said the state understands that the relatively higher costs for EVs can be a barrier to ownership for lower-income residents, but she reiterated the lower long-term costs associated with the vehicles. She also pointed out that ACC II rules contain provisions intended to ensure that EVs be transitioned to the used car market and assure that automakers provide vehicles that are durable, offer a minimum driving range, provide sufficient warranties for batteries and other parts and allow for DC fast charging.

“Because, you know, for those who may not have access to home charging, they’re going to be more reliant on public fast charging, and so ensuring that there’s that capability for the vehicles will help overall,” Sakata said.

Advisory Committee member Victoria Paykar, transportation policy manager at Climate Solutions, said that low-income areas and communities of color have lower access to EV charging infrastructure. Paykar encouraged the DEQ to partner with the state’s Department of Transportation to ensure that charging stations with competitive rates and services be made available in those communities.

Impacts on Mom and Pop

The DEQ has less insight into the financial impact of the ACC II rules on businesses outside the auto industry. Sakata said the rule change would likely represent one of the “largest growth opportunities” for electric utilities, while EV infrastructure provides should also benefit. Traditional auto parts suppliers will probably lose some business, while suppliers of batteries and other EV parts would see increased sales.

Sakata noted that the estimated 1,800 small automobile repair shops across Oregon could see “negative fiscal impact” from the transition to EVs, given their smaller number of moving parts compared with gas-powered cars.

“So, this trend overall suggests that the number of businesses providing these services may decrease along with a reduced demand over time. However, there will still be gasoline vehicles on the road for well past the regulation time frame,” Sakata said.

Committee member Glenn Choe, a regulatory affairs specialist at Toyota, asked if the DEQ had modeled the economic impact of the rules on smaller “mom-and-pop” gas stations.

“Because what we could anticipate is that the smaller gas stations go away, and the larger gas stations like the ones from Costco or the grocery stores take over, that there is some loss of pricing power for consumers, given the fact that larger entities could have a greater influence on gasoline or fuel availability and also pricing,” Choe said.

“We have not done any specific modeling for the mom-and-pop businesses; that was a little harder for us to sort of be able to quantify,” Sakata said.

Speaking during the public comment period of the meeting, Michelle Detwiler, executive director of the Renewable Hydrogen Alliance, pointed to the apparent interchangeability of the terms “ZEV” and “EV” during the meeting. She said her organization would continue to “beat this drum” around the fact that California intended that all ZEV technologies be given equal emphasis under the ACC II rules — including fuel cell vehicles.

“I also wanted to mention that all of the health benefits in particular that will accrue to disadvantaged [and] overburdened communities from the adoption of EVs will also accrue to those communities from fuel cell electric vehicles,” Detwiler said.

Sakata said the DEQ plans to hold two more public meetings on the ACC II rules in mid-October, after issuing its proposed rulemaking next week. The department will seek approval for the final rule from Oregon’s Environmental Quality Commission in December.